譯者按:頂禮本師釋迦牟尼佛!恕譯者才疏學淺,未明心要,謬誤在所難免,僅供參考。所譯文字未經上師認可,或專業翻譯機構校對,純以個人學習為目的,轉載或引用請慎重。

DA: Welcome everyone. So great to have you all here. I'm Daniel Aitken and welcome to tonight's episode of the Wisdom Dharma Chat, and on this auspicious day, we have a very special episode because we are joined by Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche, to celebrate the launch of the 84000 mobile app. So let me first introduce Rinpoche. Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche, born in Bhutan, is a student of some of the leading Tibetan Buddhist masters of the 20th century including Kyabje Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, Kyabje Sakya Trizin, Kyabje Dudjom Rinpoche, and the 16th Karmapa. As the head of Dzongsar monastery in Tibet, and Dzongsar Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö College of Dialectics in India, Rinpoche is currently responsible for the care and education of over 2000 monks distributed between six monasteries and institutes in Asia. In addition, Rinpoche oversees the nonprofit organizations of Khyentse Foundation, 84000: Translating the Words of the Buddha, and Lotus Outreach International. Rinpoche has authored several popular books on following the Buddhist path in the contemporary world, including: What Makes You Not a Buddhist; The Guru Drinks Bourbon; and Living as Dying: How to Prepare for Death, Dying and Beyond. Rinpoche has also experimented with filmmaking as a medium through which to peak contemporary interest in the Dharma. His films include: The Cup; Vara: A Blessing; and Looking for a Lady with Fangs and a Mustache. Welcome Rinpoche, and thank you for joining us.

丹尼爾: 歡迎大家。很高興你們都來了。我是丹尼爾·艾特肯,歡迎來到今晚的《智慧佛法談》。在這個吉祥的日子裡,我們有一個非常特別的節目,我們請來了宗薩欽哲仁波切,以慶祝 84000 手機 APP 的推出。所以讓我先介紹一下仁波切。宗薩欽哲仁波切出生於不丹,是 20 世紀一些著名藏傳佛教上師的學生,包括怙主頂果欽哲仁波切、怙主薩迦崔津法王、怙主敦珠仁波切和第十六世大寶法王。作為西藏宗薩寺和印度宗薩欽哲確吉羅卓學院的主理人,仁波切目前負責照顧和教育超過 2000 名僧人,他們分佈在亞洲的六個寺院和研究所。此外,仁波切還負責監督欽哲基金會,84000 佛經翻譯項目,以及蓮心基金會等非營利組織。仁波切撰寫了幾本關於在當代世界追隨佛教法道的暢銷書,包括《正見》(又譯:近乎佛教徒),《上師也喝酒》,以及《活著就是邁向死亡》。仁波切還嘗試用電影作為媒介,使當代人對佛法的興趣達到高峰。他的電影包括《高山上的世界杯》(又譯:小喇嘛與世界杯),《瓦拉:祈福》(又譯:舞孃禁戀)和《尋找一位有獠牙和鬍子的女士》。歡迎仁波切!感恩您的到來!

DJKR: Thank you. Thank you for inviting me.

仁波切: 謝謝你。謝謝你邀請我。

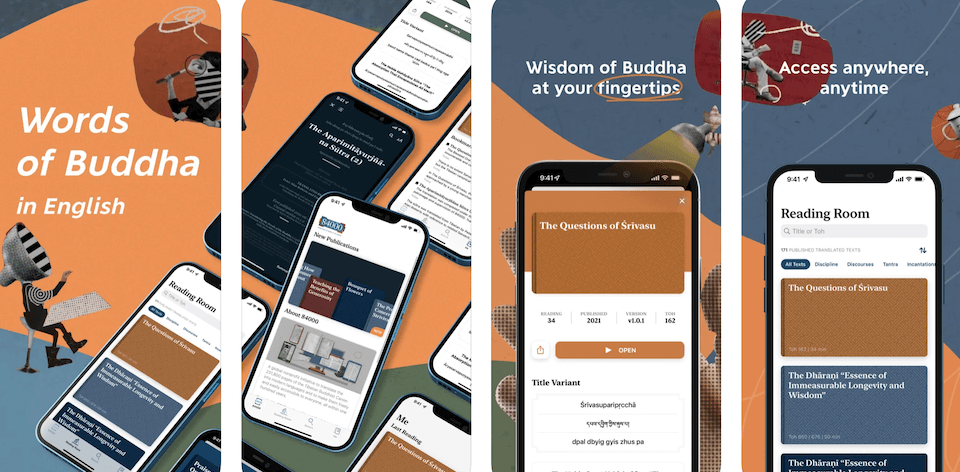

DA: So I'll just talk a little bit about tonight's program. The interview will run for about an hour and after that we'll have a short intermission and we're going to show a video to officially launch the new app. Then we will return for a question and answer session. So the audience, you all get to ask Rinpoche your questions, and you do that by entering a question in the Q&A panel at the bottom of your screen. And also we have a translation for Chinese available as well. So those questions in Chinese can get translated. So that's wonderful as well. So Rinpoche, today we're celebrating the launch of the 84000 mobile app. It's quite an achievement for you and Jing Rui and all the team. It's so hard to create this new technology. And it's so amazing that we now have that available. And so Rinpoche I was asking if you could tell us a little bit about 84000 and how and why you became involved in this project.

丹尼爾: 我談一下今晚的節目。先有一個小時左右的訪談,之後我們會有一個短暫的中場休息,我們將播放一段視頻,正式發佈新的 APP。然後,我們回來進行問答環節。所以觀眾們,你們都可以向仁波切提問,你們可以通過在屏幕下方的問答面板上輸入問題來提問。此外,我們還提供了中文翻譯。所以可以提中文的問題,真好。仁波切,今天我們慶祝 84000 移動 APP 的推出。這對您和淨蕊以及整個團隊來說是一個相當大的成就。開發這種新技術是如此困難,而現在我們能有這樣的機會,真是太了不起了。因此,仁波切,我想請您告訴我們一些關於 84000 的情況,以及您是如何和為什麼參與這個項目的。

DJKR: Well, again, thank you so much for inviting me. First, I should really say this, you know, in Buddhism, there is I believe, something called karma, karmic debt, karmic links, so on and so forth. Actually the real work of 84000 is really done by translators, administrators, sponsors. I really don't do anything. Therefore, I don't know even much of what goes on, but somehow I have this karma - I don't know whether it's good will good or not - somehow I always get quite big credit. I don't know when that's going to run out, but anyway. Well I'm a Buddhist as by now, everybody must have noticed, it doesn't mean that I'm a Dharma practitioner. Just being Buddhist, being born as a Buddhist, groomed as a Buddhist. So as a Buddhist, I'm someone who thinks that Buddhism is answer for everything.

仁波切: 好的,再次非常感謝你邀請我。首先,我應該說,在佛教中,有一種東西我們叫做業力、或者業債、或者業力聯繫,諸如此類。事實上,84000 的真正工作是由翻譯、管理員、贊助人完成的。我真的什麼都不做,我甚至不知道發生了什麼,但不知何故,我有這種業力(不知道是好還是不好),我總是得到全部的榮譽。我不知道好運什麼時候會用完,不過也沒關係。至少到目前為止,我是一個佛教徒,每個人都能看得出來,但這並不意味著我是一個佛法修行者。只是一個佛教徒,生而成為一個佛教徒,被培養為一個佛教徒。所以,作為一個佛教徒,我是一個認為佛教可以解決一切問題的人。

DJKR: In fact, more and more as I get older, as I see the situation in the world, Buddhism has incredible view on our personal life on the world in general. Buddhism does not see the world black and white. Buddhism does not see a world in terms of right and wrong. Many times what is meant by ethical or moral in Buddhism is really different from a lot of other thoughts and philosophy and ways. Buddhism really offers ways and tools and techniques of how to see the world as it is rather than how it appears. So I think I, as a Buddhist, strongly believe that Buddhism has a very, very important role in the world - has always been - but more so now than ever. As a Buddhist, I feel that we need to really protect, propagate, preserve the Buddhadharma.

仁波切: 事實上,隨著我年齡的增長,隨著我目睹當今世界的各種情況,佛教對我們個人的世俗生活有著不可思議的見地。佛教不以黑和白來看待世界。佛教不以對與錯來看待世界。很多時候,佛教中的倫理道德的含義,與很多其他思想、哲學和方法大不相同。佛教提供了如何看待真實世界的方法、工具和技巧,而不是它的表象。所以我認為,作為一個佛教徒,我堅信佛教在這個世界上有非常非常重要的作用,過去一直如此,但現在更為重要。作為一個佛教徒,我覺得我們需要真正去保護、宣傳和保存佛法。

DJKR: And this is also something that I have been sort of been expected to do by all my masters that you have just mentioned, which made me shudder a little bit because, you know, that's a really - I shouldn't really say burden, but it's there - it's a weight. Buddhism had so many challenges: outer, inner, and secret challenges, as you know. Historically, Buddhism had lots of problems in traditional Buddhists countries, societies. Most of the external problems, I don't think is something that we should be too concerned about, like destruction of the monasteries, or I don't know. I don't think that is something that we have to be too concerned with. I think the main degeneration of the Buddhism will come within the Buddhists, in terms of how we interpret the Buddhist wisdom. And especially, as you know—more than anyone you would know because you basically live inside the books—interpretations, words, language, these things constantly evolve.

仁波切: 而這也是我所有的上師(你剛才提到的)要求我去做的事情,這讓我有點不寒而慄,因為(我真的不應該說是負擔,但確實是)它是有重量的。如你所知,佛教有如此多的挑戰:外在的、內在的和秘密的挑戰。從歷史上看,佛教在傳統的佛教國家和社會有很多問題。我不認為大多數外部問題,比如寺院被破壞,是我們應該過於關注的事情。我認為佛教的衰敗將來自佛教徒內部,就我們如何解讀佛法智慧而言,特別是這些解釋、文字、語言(你比任何人都清楚,因為你基本上生活在書本里)這些東西不斷地演變。

DJKR: And because of that, for instance, what is ‘meditation’? What is meant in Buddhism by words like ‘meditation’ ‘compassion’? It really does have a different meaning sometimes altogether. So, these things need to be properly addressed. And, yes, there has been a lot of effort, incredible effort, not just from the lamas, and the monks, the Zen masters, the Theravadan masters, Tibetan lamas, but even by students. I remember when I was growing up in Nepal, there was all these hippies, who really, they weren't that well off. They were really struggling, and they put so much effort into translating. So, there has been lot of translation of Buddhadharma, which is something to rejoice in. You know very well that translating anything is difficult. A few months ago I was reading Murakami's novel, which is really—I don't know, maybe Murakami might not like to hear this, but—it's not that profound. It's a story. And my Japanese friend told me that if only you speak Japanese, it is much more interesting and juicy and all of that.

仁波切: 比如說,什麼是「禪修」?在佛教中,像「禪修」「慈悲」這樣的詞是什麼意思?它有時確實有完全不同的含義。所以,這些事情需要得到適當的解決。是的,已經有很多人在努力,難以置信的努力,不僅僅是出家人們、禪宗大師們、上座部大師們、西藏喇嘛們,甚至還有學生們。我記得我在尼泊爾長大的時候,有些嬉皮士們,他們並不富裕,他們很掙扎,而他們在翻譯方面付出了很多努力。所以,有很多佛法的譯本,這是值得高興的事情。你很清楚,翻譯任何東西都是困難的。幾個月前,我正在讀村上春樹的小說,我覺得它並不那麼深刻(村上可能不喜歡聽我這麼說),只是一個故事。而我的日本朋友告訴我,如果你會日語,讀日文原版,它就會變得更有趣,更刺激。

DJKR: So, translating words of the Buddha is something that we need to be constantly mindful about, putting in effort, putting in alertness. And this is why, about ten years ago, we had a serious meeting and conversation with the lamas and translators about what we can do for the world of translating the words of the Buddha now and as time goes [on]. So, this is how—in Bir—84000 was conceived. And I have to say, translation work is not—sorry for being very crude—but it's not a ‘sexy’ job. It's not that exciting. It's not like painting gold on the roof of a temple, you know, you can see and you can get really like excited.

仁波切: 所以,翻譯佛陀的話語是我們需要不斷地放在心上,投入努力,很警覺的事情。這就是為什麼,大約十年前,我們與一些喇嘛和譯者進行了一次認真的會議和談話,討論現在和未來,隨著時間的推移,我們可以為翻譯佛經做些什麼。這就是在比爾 (譯:印度北部的小鎮) ,84000 這個項目是如何構思的。我必須說(抱歉我說得很粗俗),翻譯工作不是一個「性感」的工作。它不是那麼令人興奮。它不像在寺廟的屋頂上塗金那樣,可以讓人看到,讓人感到興奮。

DJKR: It's really difficult. I'm not a translator. In fact, as you can hear as I speak, I don't speak proper English and—of course, that you can excuse me—but actually I don't even speak proper Tibetan. And I say, this not out of you know a usual Tibetan practice of humility, I really mean it. Because Tibetan language is really a difficult one. I have not really studied Tibetan language because I went to study Buddhist philosophy. And most of my philosophy teachers… their attitude towards languages such as poetry or grammar are like, ‘it's a distraction.’ So now I realize I'm very ill-equipped from both points of the language. Translation is an incredibly difficult job. And it's so much responsibility. Not just the actual technical work, but you are taking on the responsibility of hundreds and hundreds and thousands of people who will be reading now and the future generations to come.

仁波切: 這件事很難。我不是一個譯者,事實上,你們聽我講話就知道,我英文說得不太好。當然,這可以被原諒,但實際上,我藏語說得也不太好。這不是出於你們認為的西藏人通常的謙虛,我真是這樣。因為藏語是一種很難的語言,我沒有真正學習過藏語,因為我是去學的佛教哲學。而我的大多數哲學老師,他們對詩和語法的態度是:「這些是散亂」。所以現在我意識到,從兩種語言來看,我的裝備都很差。翻譯是一項極其困難的工作,它的責任非常大。不僅僅是實際的技術工作,而且你還要對成千上萬的讀者負責,包括現在和未來的一代代讀者。

DJKR: So, I really admire all translators—not just for 84000. We need to have some sort of organized fashion, organized way of translating the words of the Buddha, because if we don't have that—while we need to rejoice—translators are springing up from all kinds of directions. There is no wish to kind of unify and create, and I think that is just almost impossible. But, we also need to know where the motivation is coming from. And also, how much dedication is being placed for this grand endeavor. So, this is why we came to some sort of conclusion to have some sort of an organized situation called 84000. So anyway, that's just a very sporadic way of answering your question.

仁波切: 所以,我真的很佩服所有的譯者,不僅僅是84000的譯者。我們需要某種有組織的、時尚的方式來翻譯佛陀的話語。其實很多譯者正從四面八方湧現出來。如果我們沒有組織,雖然我們很隨喜他們,但沒有向統一性和創造性的方向發展,而且我認為這些也是不可能做好的。同時,我們也需要知道他們是出於怎樣的發心,還有,能為這一宏偉的目標付出多少心血。所以,這就是為什麼我們得出了一個結論,要有一個組織,取名為 84000。這只是一個非常零散的方式來回答你的問題。

DA: Thank you Rinpoche That was very clear. And it seems it's important that this is not just an effort to save this historical artifact. You're saying that, actually, this has the wisdom to help with today's problems, all of today's problems, you said, Rinpoche. And so that's an important point. And I was wondering—this question might seem to have an obvious answer—why did you start with the Kangyur, you know, the Buddha's words? Often in the monasteries, it seems that it's the Tengyur that's being studied and the commentaries. So why did 84000 start with the actual Buddha's words?

丹尼爾: 感恩仁波切,您已經說得非常清楚。而這似乎是很重要的,這不僅僅是為了拯救歷史文物的努力。實際上,這裡有幫助解決今天所有的問題的智慧,這是仁波切您說的。這是一個重要的觀點。我想問(這個問題似乎有一個顯而易見的答案)您為什麼要從《甘珠爾》(佛陀的話語)開始?通常在寺院裡,人們研究的似乎是《丹珠爾》和很多註釋。那麼,為什麼 84000 要從真正的佛語開始呢?

DJKR: Very important question. Thank you, actually, for this question.

仁波切: 非常重要的問題。謝謝你提了這個問題。

DJKR: Yes, there has been, as I said earlier, there has been a lot of effort in translating the words of the Buddha. I mean, words of the Buddha in general. But often especially with the Tibetan tradition—you are very right—somehow the Tibetans got really… the Tengyur and the commentaries really hijacked Tibetan Buddhist study. I really admire Chinese and the Mahāyāna tradition, and the Theravada tradition who, really, you know, they put so much emphasis on studying the actual Buddhist teachings. I guess, you know, like Chandrakirti—one of the great commentators—he said that the words of the Buddha himself, the sūtra, are very difficult to understand. Only the one who has achieved the Bhumis can understand. And he attributes to Nagarjuna, saying that only through the help of Nagarjuna's commentary, am I making a commentary so on and so forth.

仁波切: 是的,一直以來,正如我先前所說,在翻譯佛陀的話語方面有很多努力。我是指通常說的佛經。但是,你說得很對,特別是對於西藏的傳統,不知何故,對《丹珠爾》和註釋的研究真的劫持了西藏的佛教。我很佩服中國和大乘傳統,以及上座部傳統,他們非常強調研究真實的佛法。就像月稱(一位偉大的註家)所說,佛陀本人的話語,即佛經,是非常難以理解的,只有登地的菩薩才能理解。而且他把自己的功勞歸於龍樹,他說只有通過龍樹的註釋的幫助,我才能寫註釋,諸如此類。

DJKR: So there's all that, these kinds of conversations. So, you know, I have been told to speak a little bit about sūtras time to time. And I always try to say this as a disclaimer. But in the process, you know, like Christians, in the end, what do they have to really boil things down to? It's the Bible. And for the Muslims, it's the Koran. And I guess for the Jews, Jewish Torah. For Buddhism, it has to come down to sūtra, words of the Buddha himself. So that sometimes gets neglected because we are so attracted to our own immediate masters and the commentators. So, this is why we deliberately, consciously chose—even though the Kangyur is actually going to be, we thought probably the least used… but very, very encouraged even to find out that somebody from Rwanda, somebody from Azerbaijan, are downloading our work. It's incredibly encouraging.

仁波切: 所以才會有這個問題。你知道的,我不時地會被要求講一點佛經,而我總是試圖說一個免責聲明。但是在這個過程中,就像基督徒最後必須回歸到《聖經》,穆斯林必須回歸到《古蘭經》,我想對猶太人來說是猶太教的《聖經》。對佛教來說,它必須回歸為經,即佛陀本人的話語。這一點有時會被忽視,因為我們被我們自己的直接上師和註釋者所吸引。因此,這就是為什麼我們刻意地選擇《甘珠爾》(雖然實際上可能是使用最少的)。但是非常非常令人鼓舞地發現,有人從盧旺達,有人從阿塞拜疆,正在下載我們的作品。這是令人難以置信的鼓勵。

DA: That's amazing, from Rwanda. You know, Rinpoche, I'm thinking people are often so eager to pick up a bell and dorje and recite a text in Tibetan and they don't understand, but to actually sit down with a sūtra, long sūtra, and read it, seems—you used the word "sexy" before—it seems not as sexy, Rinpoche. So how should we think about the sūtras, and engaging with the sūtras to be inspired, to engage with those texts?

丹尼爾: 真了不起,來自盧旺達的下載。仁波切,我在想,人們常常非常渴望拿著鈴杵,用藏語背誦經文,但他們並不理解,但真正坐下來,拿著一部經,長長的經,去讀它,似乎並不那麼性感(您之前用的這個詞)。那麼,我們應該如何看待佛經,如何融入經文,以求得到啟發?

DJKR: Yes. I think this is very important, and I'm actually seeking help from you guys to really make this… And I was just talking to your two marketing ladies—and I'm actually going to ask them to also help me, to give me some ideas on how to market—and not in the sense of making, you know, sort of monetary profit. Because basically marketing is what in the teaching, we call it [Quotes in Tibetan]. You have to understand people's capacity, faculties, what is their background? What is their culture? And according to that, the Buddhist teachings should be taught. Because there is this comment, which is very important, Buddha never taught teachings because he knew the subject of the teaching. He was not like a professor who was doing his job. He taught all his teachings out of compassion, to different people.

仁波切: 我認為這非常重要,而且我正在尋求你們的幫助,我剛剛和你們的兩位負責營銷的女士談過,實際上我打算請她們也幫助我,給我一些關於如何營銷的想法,不是在賺取金錢利益的意義上。因為營銷在佛法的教學中被稱之為(藏語),你必須瞭解人們的接受能力,他們的背景是什麼?他們的文化是什麼?並根據這一點來教授佛法。因為有這樣的說法(非常重要),佛陀從來沒有真正教學,因為他了解接受教法的主體。他不像一個教授在做教授的工作,他的教學工作完全是出於慈悲,對不同的人的慈悲。

DJKR: Coming back to your vajra and bell—dorji and drilbu—example, very important: people are almost always attracted to the method. The means, never the end, always end up looking at the finger, not the moon, because the finger is kind of nice, especially when it is decorated with the rings and bangles and you know, all of that. So, like for instance, the very popular thing that's going on these days, like a Vipassana or the meditation. That's a means by the way, that's not the end. So how many people here today are attracted to ‘mindfulness,’ cushions, sitting straight, walking very slowly, all of that, they are very attracted; but the view, hardly people have time. So, another reason why we need to translate texts like Prajñāpāramitā where Buddha really give us the Buddhist view. Because if you forget the view, then the rest of Buddhist is just another survival kit.

仁波切: 回到你說的金剛杵和鈴鐺的例子,非常重要的是:人們幾乎總是被方法所吸引。手段從來都不是目的,而人們最後總是在看手指,而不是月亮,因為手指太漂亮了,特別是當它被裝飾上戒指和手鐲,等等等等。比如說,這些日子非常流行的東西,比如內觀和禪修。順便說一下,那也只是一種手段,那不是目的。而今天有多少人被「正念」所吸引?打坐墊,背要直,動中禪,等等等等,他們都非常吸引人。但是見地呢,幾乎沒有人有時間去了解。這是另一個原因,我們需要翻譯像《般若波羅密多》這樣的經文,在那裡佛陀真正給了我們佛教的見地。因為如果你忘記了佛教的見地,那麼佛教的其他部分就只是另一個生存工具包。

DA: So, this form, people are attracted to forms, but it is the view that counts, right? And that's why we need to spend time with these sūtras. It's also, Rinpoche, like you were mentioning, meditation and it seems like everyone is into gom, but tö and sam—listening and contemplating—there's less focus on that. So, it feels like with the tools, with the sūtras, they're available, literally at our fingertips now, Rinpoche, because they're in an app on our phone, so we can spend time with these. And so, Rinpoche, do you have any advice for how to engage? Like how should we be engaging? We have all these texts now at our fingertips. How should we use them?

丹尼爾: 所以,人們被形式所吸引,但重要的是見地,對嗎?這就是為什麼我們需要花時間在這些經文上。仁波切,就像您提到的禪修,似乎每個人都喜歡修,但聞和思卻不太注重。所以,我覺得有了這些工具,有了這些經文,它們現在就在我們的指尖上,因為它們在我們的手機上的一個 APP 裡,所以我們可以花時間在這些上面。那麼,仁波切,對於如何融入您有什麼建議嗎?現在我們的指尖就有所有這些經文,我們應該如何使用它們?

DJKR: Tell me about what you were just saying is so true. There is really not enough effort—we as teachers and also the student—we put in tö and sam, which is hearing and contemplation. And when we say ‘hearing’ we are not talking about somebody talking, and then you listening. Basically it's like downloading 84000 app. You switch it on and then you choose, okay, how much time do you have, do you have ten minutes? There's a ten minutes sort of length sūtras, so you read that that day. What do you want to know? You read. Reading is in this case, is what we call ‘hearing,’ the hearing and the contemplation also, absolutely important. Otherwise, there has been problems that's related to Buddhists, especially with the teachers and the organizers and the Buddhist centers, behaviors, why? There hasn't been enough reading. There hasn't been enough analysis. And this is the frustrating part actually. I mean, Buddha said “analyze my teaching. Don't follow blindly.” This guy said this 2,500 years ago, this is a statement as old as 2,500 years ago, that's like the most liberal thinking. This is the most democratic thinking. And sometimes it's mind-boggling that we don't do that.

仁波切: 你剛才說的特別對。作為老師和學生,我們在聞思方面所做的努力真的不夠。當我們說聞的時候,我們不僅是指某人在說話,然後你在聽。聞還可以包括下載 84000 APP。你打開它,然後你可以選擇。你有多少時間,你有10分鐘嗎?選一個 10 分鐘長度的經文,然後你那天就讀那個。你想知道什麼就去讀。在這種情況下,閱讀就是我們所說的聞。聞思也是絕對重要的。否則,佛教徒就會出問題,特別是與老師、組織者和佛教中心有關的問題,行為上的問題,為什麼?沒有足夠的閱讀,沒有足夠的分析。這也是令人沮喪的部分。我的意思是,佛陀說「分析我的教言,而不要盲目跟隨。」這傢伙在 2500 年前就這麼說了,這是一個 2500 年前的宣言,這就像最自由的思維,最民主的思維。而我們不這麼做真是令人匪夷所思。

DA: Yeah. And partly now you have access to the text so you can get a bigger picture as well, so that you can analyze in a more thorough way as well. So, I think that's an advantage of us having that. But then there is the other side of the coin, which is, you know, in the book industry, when we in back in the days before Amazon, and you wanted to get a Buddhist book, there was very limited selection at the bookstore. Now, if you go to Amazon and you type in Buddhism, there's like over 20,000 results. And it's like, what should I read? So Rinpoche, as we are getting access to all these texts that were inaccessible before and now on our app, we might have, I think in the website says the Kangyur has 72,000 pages: how do we know where to start for example?

丹尼爾: 是的。而且現在你有機會接觸到經文,所以你也可以得到一個更大的視角,你也可以以更徹底的方式進行分析,我想這是我們擁有的一個優勢。但是,硬幣的另一面是,你知道,在圖書行業,當我們回想有亞馬遜之前的日子,你想得到一本佛教書籍,在書店的選擇非常有限。現在,如果你去亞馬遜,輸入佛教,就會有超過 20,000 個結果,那我應該讀什麼呢?所以,仁波切,當我們獲得所有這些以前無法獲得的經文,例如在我們的 APP 上,(網站上說)僅甘珠爾就有 72,000 頁,我們該如何知道從哪裡開始呢?

DJKR: Wow. Very important question. It all now boils down to us student and the practitioner. Are we motivated to practice, study? Do we have enough longing for the truth? Because as far as facilities on some, as you put it very clearly, it's so easy when I was 14 and 15, I first started studying Mādhyamika in India. This was in the 1970s. We had 18 students and all 18 students shared one Mādhyamikavatara text. So, it was like from one to two [p.m.] it's yours, two to three [p.m.] That's how it was. And even at that time, because the students were really dedicated—I mean, some of the students had to like stay up quite late because their turn doesn't come [until then]—now it's in your fingertips. So, I hope that this accessibility will not also invoke complacency and the lack of aspiration.

仁波切: 哇喔,非常重要的問題。這一切都取決於我們這些學生和修行人,我們是否有動力去修行、去學習?我們對真理有足夠的渴望嗎?因為就設施而言,正如你所說,現在真是太容易了。當我 14、15 歲的時候,我第一次在印度開始學習中觀,那是在 1970 年代,我們有 18 個學生,所有 18 個學生共享一本《入中論》課本。例如從下午 1:00 到 2:00 是你的,2:00 到 3:00 是他的。在那個時候,學生們真的很精進,有些學生不得不熬夜,因為直到很晚才輪到他們。而現在,它就在你的指尖上。因此,我希望這種觸手可及不會也招來自滿和缺乏渴望。

DJKR: I want to actually say this, this is something that we need to actually—Daniel, maybe you could even help me on this one with your team—you know the traditional Buddhist societies such as Tibetans, we have concepts such as merit-making, merit, sonam. So, what we do is we sponsor to carve a woodblock of one text, like [Speaks Tibetan] Fortunate Aeon, we actually have a tradition of carving it on rocks. So, in Tibet it's very popular or printed on fabric and then hoist as flags, so on and so forth. Somehow, we need to really teach—not just Tibetans, but many other people—that it is equally, if not more, full of merit to create the software, create the design. Marketing.

仁波切: 我想說的是,這實際上是我們需要的東西。丹尼爾,也許你可以和你的團隊一起幫助我。你知道傳統的佛教社會,比如藏人,我們有功德的概念,要做有功德的事等等。我們所做的是,我們贊助雕刻一個經文的木版,像《賢劫經》。我們實際上有一個在岩石上雕刻的傳統。還有,在西藏非常流行的,印在織物上,然後作為風幡,等等等等。而現在,我們需要教導(不僅僅是西藏人,還有許多人)為佛經編寫軟件、做設計、做市場營銷,也同樣充滿了功德。

DJKR: You could be helping to market something like Mahākaruṇa Sūtra, and reach Rwanda, Somalia, whatever. And imagine the merit, right. In one moment you can do this. So, this is something that I think modern Buddhists, we need to sort of really learn, because I think the teachers, we need to sort of adapt you know? But it's difficult sometimes because we still feel like, “Oh, it's better to offer butter lamp rather than electricity lamp,” because you think it's kind of romantic. I understand. While we are here, I need to really offer my gratitude towards those who created this app and also our videos and all the… ‘marketing’ is probably not the most spiritual sounding word, but I really have to appreciate it.

仁波切: 你可以幫助推銷像《大悲經》這樣的東西,推銷到盧旺達、索馬里。想象一下這種功德,而且你立即可以做到這一點。所以,這是我認為現代佛教徒,真正需要學習的東西。我們老師也需要適應時代。但有時很難,因為我們仍然覺得「供奉酥油燈比供奉電燈好」。如果你這麼想是因為浪漫,那我可以理解。我們達到這一步,我需要對那些創建這個 APP 和我們的視頻以及所有參與營銷(聽起來可能不是一個那麼靈性的詞)的人表示感謝。我真的要感謝他們。

DA: Yes, I totally agree. And then knowing that, so you can dedicate that merit as well. Cause if you don't know that this is a merit-making activity and how powerful it is, then you won't take the time to dedicate. I had so many thoughts around puṇya, merit. Right? And, you know, with text and recitation, and I was wondering just as a fun question, Rinpoche: In old Tibet they would often pay someone to recite a text for them, right? And now we have computers that can read the text to us. And so, these sorts of things, is this merit-making for you? Or how do you think about those sorts of things?

丹尼爾: 是的,我完全同意。知道這一點,你也可以把這個功德迴向。因為如果你不知道這是一項創造功德的活動,不知道它的力量有多大,那麼你就不會花時間來迴向。我有很多想法都是圍繞著功德,是吧?而且,對於念誦經文,我有一個有趣的問題,仁波切:在過去的西藏,他們經常花錢請人為他們誦經,對嗎?而現在我們有電腦,可以給我們讀經文。那麼,這類事情是有功德的嗎?或者說您是如何看待這類事情的?

DJKR: You know, [Quotes in Tibetan] this is what Buddha said, ‘motivation.’ This is probably one of the subtle, but a very important difference between a lot of the interpretations of ‘karma’ in Hinduism and karma nowadays. The word ‘karma’ is kind of used by everybody, but in Buddhism, a big chunk of karma ingredient is actually motivation. So even with the motivation—and I'm really being serious here—let's say you are so busy, but you want to quickly accumulate merit with just motivation to go into 84000 reading room, just for a moment. And actually, I'm not only talking about the 84000, any of the Dharma books, just open the Dharma books, or even browse Amazon’s Dharma books, with a motivation to visit and look at the Dharma text titles just for even like ten seconds. There is merit. And I'm not making this up. This, Buddha himself said. In the sūtras, you can usually read, even if you have the texts [Quotes in Tibetan], even if you have the texts somewhere in your house or in your bag, you have merit. So, as long as you have a motivation and some effort of switching it on, of course you have merit.

仁波切: 這就是佛陀所說的:發心 (譯:英文字面意思是動機) 。這可能是印度教以及現代人對業力的理解,和佛教對業力的理解之間的一個微妙的但非常重要的區別。業力這個詞有點被大家濫用,但在佛教中,業力很大一部分的成分實際上是發心。因此,有了發心(我真的是很嚴肅的),比方說你很忙,但你想快速積累功德,只需帶著合適的發心,進入 84000 線上閱覽室,只需一會兒。實際上,我不僅是在說 84000,任何一本佛法書籍,只要打開佛法書籍,甚至瀏覽亞馬遜的佛法書籍列表,帶著發心地去看一看佛法書的標題,哪怕只有十秒鐘,就有功德。這不是我編造的,佛陀自己就這麼說過。佛經中說,你可以閱讀,或者即使你擁有經文,即使你在家裡某個地方或在你的包裡存放著佛經,你也有功德。所以,只要你有發心,然後花一點點力氣打開這個 APP,你當然就有了功德。

DA: Intention. So, Rinpoche when people are making the app, they also have to know that this is a Dharma activity. They're not just making something, it's a Dharma activity, so they can have the intention for the benefit of all people as well. And just something else came to my mind actually: now that we have all the Dharma texts on here, it's amazing to be able to make merit just by opening it up and reading the different titles. But then I was also thinking this [mobile phone], now put it in my pocket, right? Is this a holy object? What about when it goes in my pocket? How do we think about that?

丹尼爾: 嗯嗯,發心 (譯:英文字面意思是意圖) 。所以,仁波切,當人們在開發這個 APP 時,他們也要知道這是一個佛法事業。他們不僅僅是在做東西,也是一個佛法事業,所以他們也可以有利益所有人的發心。實際上,我還想到了另一件事。現在我們這裡有所有的佛法典籍,只要打開它,閱讀不同的標題,就能製造功德,這確實很了不起。但後來我也在想這個手機,現在把它放在我的口袋裡,像這樣。這是一個聖物嗎?當它放進我的口袋時,發生了什麼?我們如何思考這個問題?

DJKR: Okay. Now, merit—puṇya—is so related to culture also, Tibetan culture. And then of course, the Tibetan concept of puṇya—merit—also goes to India, to the Indians. For instance, Tibetans offer imaginary lotus flowers. But I mean, pre-1959, most Tibetans don't have a clue about what is ‘lotus’—lotuses don’t grow there. So, what I'm saying is, in Asian culture like putting holy objects—stepping over holy objects or putting this [mobile phone] in pocket—yes, so there's that. Now, this is why the Buddhist idea of karma is so profound: because now having heard this from now on, if you do even feel a little bit guilty for putting the phone in your pocket here—because I have, you know, the sūtras here—you're already creating merit; or putting your phone on your head because there is a Dharma text, you are creating merit. And probably in your phone, who knows what other things you have probably, but that doesn't matter. It's your motivation.

仁波切: 功德這個詞,也與藏人文化有關,當然,西藏的功德的概念也可以追溯回印度人那裡。例如,西藏人供養觀想的蓮花。但是,在 1959 年以前,大多數西藏人對什麼是「蓮花」沒有概念,因為蓮花無法在西藏生長。所以,我想說的是,在亞洲文化中,踩在聖物上或把聖物放在口袋裡,確實是有問題的。現在聽好,這就是為什麼佛教的業力的概念如此深刻:你從現在聽到這個開始,如果你確實因為把手機放在口袋裡而感到有點內疚(因為我有),你已經在創造功德。或者把手機放在頭頂,因為有佛法的經文,你已經在創造功德。在你的手機裡,誰知道你還有什麼其他東西,但這並不重要。這是你的發心。

DA: Nice. Rinpoche. Thank you. While we're on the topic of merit puṇya, There's a lot of people who are so-called Buddhist "skeptics", and I know you have fun with them Rinpoche, but how do you talk about merit? How do you explain merit to a new Buddhist? You know, someone comes in and sits down with you, and you start talking about merit. How do you explain that concept to them?

丹尼爾: 太好了。仁波切,謝謝您。當我們談及功德的話題時,有很多人是所謂的佛教「懷疑論者」,我知道仁波切您對他們很感興趣,但您如何跟他們談論功德?您如何向一個新的佛教徒解釋功德?

DJKR: Okay. Very important question. Let me twist this a little bit. In Buddhism, there is no concept of sin. There is ignorance, just as many other religions are very cautious of sin. Buddhists, ideally, should be cautious of ignorance. Now, what does this tell us about puṇya, about merit? At the end of the day, how do you define what is merit and what is not? At the end of the day, any action that takes you closer to the truth, that is merit. If you offer a hundred thousand lotuses, but if it only enhances your ego, takes you further from the truth, it’s not really merit in this case. So, anything that unveils, anything that takes you closer to the truth is basically merit because you see fundamentally… Remember if Wisdom, Compassion, and Morality, are going for a drive Wisdom should be the driver. The Compassion should be sitting next to the driver, Morality - maybe backseat, sometimes even in the trunk. Because all these, you know, like morality, generosity, mindfulness, all of this… without Wisdom they're a pain in the neck.

仁波切: 好的,非常重要的問題。讓我把這個問題稍微扭曲一下。在佛教中,沒有罪的概念,有的是無明 (譯:英文字面意思是無知) 。就像許多其他宗教對罪惡非常忌諱一樣。佛教徒,在理想情況下,應該對無明非常忌諱。那麼,這對功德有什麼啟示?最終,你如何定義什麼是功德,什麼不是?說到底,任何能讓你更接近真理的行為,都是功德。如果你供養了十萬朵蓮花,但如果它只是增強了你的自我,使你離真相更遠,在這種情況下,它就不是真正的功德。所以,任何揭示真理的事情,任何讓你更接近真理的事情,基本上都是有功德的。請記住,如果智慧、慈悲和道德,要開車去兜風,智慧必須是司機。慈悲應該坐在司機旁邊。道德呢,也許是後座,有時甚至是在後備箱。因為所有這些,像是道德、佈施、正念禪修,如果沒有智慧,它們都只是痛苦。

DA: I see Compassion with the map, you know, and wisdom driving. Very nice. This is a nice explanation. It's a skillful activity, right. It's kaushalya as well. And it's also action, but not just action, it's action driven by wisdom. There's close connection here. You're talking about karma and also wisdom coming together almost.

丹尼爾: 慈悲在看地圖,輔助智慧駕駛。太好了。這是個非常好的解釋。什麼都是善巧方便,這非常重要。它也是行為,但不只是行為,它是由智慧驅動的行為。這裡有密切的聯繫。您說的業力和智慧幾乎是一起的。

DJKR: Yes. Always. Karma without the wisdom. Oh, that's dangerous.

仁波切: 是的。一直都是。不帶智慧去理解業力,是很危險的。

DA: Wow. Rinpoche. This is so nice. Rinpoche you mentioned before, and it's an image that's in my mind now that you had one Mādhyamikavatara text between your whole class and you're sharing it around: It's incredible how things have changed. And I'm wondering, for you now, thinking back to those days and comparing them to today, in terms of how you use technology, we can say, technology to study and to teach: what's it like today compared to those days?

丹尼爾: 哇。仁波切,這真是太好了。仁波切剛才您說到,很有畫面感的是,您全班同學只有一本《入中論》課本,要與周圍的人分享,事情的變化真是不可思議。我想知道,對您來說,回想那些日子,並與今天進行比較,就您如何使用技術而言,就技術用來學習和教授而言,與那些日子相比,今天是什麼樣子?

DJKR: You know, as I said earlier, it all boils down to me now. I have the responsibility. Now I have no excuse. You know, thirty years ago, forty years ago, I have an excuse, ‘Oh, I don't have a text, this is not my time yet. So I don't have to study and practice.’ Now there isn't. I have a lot of texts in my phone and I have to say more than ever—this time during the pandemic time, when there's a lot of lockdown and quarantine situation, I have to say—this has been a lifesaver. Of course, I also watch Netflix, but this [technology] has been so incredibly helpful. Like I need to, let's say I have a little bit of a doubt on a certain meditation technique or whatever. I just ask one of my monks or download texts from like Tsadra Foundation, for instance, then it's there.

仁波切: 你知道,正如我先前所說,現在一切都歸結於自己,自己有責任。現在我沒有藉口了。三十年前,四十年前,我還有一個藉口:「哦,我沒有課本,現在還沒輪到我用課本,所以我不學習不修行。」現在沒有了。我的手機裡有很多經文,我不得不說,在疫情期間,當有封城和隔離的情況時,電子書比以往任何時候都要重要,可以消磨時間。當然,我也看 Netflix,但電子書非常有用。比方說,我對某種禪修技巧或其他方面有一點疑問,我可以問我手下的出家人,或者從 Tsadra 基金會下載電子書,然後就有了。

DJKR: And not only that, but before if I needed to have a specific explanation, I needed to go through all the pages. Now, just key in the word and it's there. And not only that, there's all the different masters and different interpretations. And when I look at the 84000 app, there's even an extra something so good about this is, because it's also bilingual, then also [definition of] terms, names… All these are so easily accessible. In general, all spiritual traditions I think, talk about Kali Yuga, degenerative time, but in Mahāyāna and especially in the Vajrayāna, our tantric masters always say, Kali Yuga is actually not necessarily a bad thing. It just means it's more volatile. Volatile can be quite profitable, if you are savvy.

仁波切: 而且不僅如此,以前如果我需要有一個詞的解釋,我需要一頁一頁去翻。現在,只要鍵入這個詞,解釋就出來了。不僅如此,還有不同上師的不同解釋。當我看 84000 APP 時,還有一個額外的好東西,因為它是雙語的 (譯:藏英雙語) ,然後還有術語、名稱等等,所有這些都是如此容易獲得。一般來說,所有的傳統靈修都在談論卡利宇迦 (譯:相當於佛教的減劫) ,但在大乘,尤其是在金剛乘,我們的金剛上師總是說,卡利宇迦實際上不一定是壞事,它只是意味著更多不穩定。如果你很精明的話,不穩定可以是相當有利可圖的。

DJKR: You know, it's like a market, I guess, when the market's volatile, these good businessmen, they make a lot of money. Now I realize that actually, I really wonder whether this is even actually a so-called degenerative dark age? Of course there's many reasons why we can think that, the ecology, the political situation, so on and so forth. But now that we have this kind of facilities [the app], no amount of outer force can destroy Buddhadharma. At least externally. Internally? Yes. We Buddhists can ruin ourselves.

仁波切: 這就像一個市場,當市場波動時,這些優秀的商人,他們賺了很多錢。現在我意識到,其實,我真的懷疑這是一個所謂的減劫的黑暗時代?當然有很多原因可以讓我們這樣想,生態環境,政治局勢等等。但現在我們有了這種設備,再多的外部力量也無法破壞佛法,至少從外部無法。從內部呢?是的。我們佛教徒可以毀掉佛法。

DA: Yes. By not studying. Is that what you mean, by not working on it?

丹尼爾: 是的。 通過不學習。這就是您的意思,不努力學習可以毀掉佛法?

DJKR: Not studying. Not practicing; being self-righteous; being sectarian.

仁波切: 不學習,不修行,自以為是,搞宗派主義。

DA: So Rinpoche in some ways we are very fortunate to have so much accessibility to the Dharma and then your main message tonight is ‘it's up to you.’ In some ways it's up to you now. Right? You have the texts.

丹尼爾: 所以,仁波切,在某些方面我們非常幸運,有這麼多的機會接觸到佛法,您今晚的主要信息是「這取決於你自己」。在某些方面,時代是由你自己決定的。對嗎?你有這些經文。

DJKR: Yes.

仁波切: 對。

DA: And then the role of a teacher in this environment, maybe from a sūtra context—because the role of a teacher from Vajrayāna is central, obviously—but in this sūtra context, the role of a teacher, when you have all these texts… What's the role of a teacher, getting these teachings, how do you think about that with technology?

丹尼爾: 然後,在這個環境中,老師的角色是什麼?因為從金剛乘的角度說,老師顯然是在中心的。但是在佛經的背景下,老師的角色是什麼?當每個人都擁有所有這些經文,都能得到這些教授,老師的角色又是什麼?在技術的背景下,您如何思考這個問題?

DJKR: Okay. I just recently read this in a sūtra—and I totally forgot the name of the sūtra… I will try to find it for you—in that sūtra it's something so important and I think it's really important: how do you define a perfect teacher? This is a Mahāyāna, by the way, we are not talking about Vajrayāna. How do you define a good teacher or a qualified teacher? That teacher must do—teach, listen, manifest, whatever he or she does—it has to one way or another, all his or her teaching method must lead to understanding of the śūnyatā.

仁波切: 我最近在一部經文中讀到這個(我完全忘記了經文的名字,我會試著找給你),在這部經文中,說了一件很重要的事,我認為它真的很重要:你如何定義一個完美的老師?順便說一下,這是大乘,我們不是在談金剛乘。你如何定義一個好老師或一個合格的老師?那位老師無論做什麼,教學、傾聽、開示,他或她的所有教學方法,都必須以某種方式,通向對空性的理解。

DA: Oh, wow. Yeah.

丹尼爾: 哇。是的。

DJKR: That, then will qualify whether the teacher is a good teacher or not. Even if the teacher himself or herself doesn't know that śūnyatā, at least make the student want that śūnyatā… already good.

仁波切: 這一點,定義了一個老師是否是好老師。即使老師自己不懂空性,至少也要讓學生嚮往空性,想要空性,那已經很好了。

DA: Yeah. Wow. So wisdom is always driving, right?

丹尼爾: 是的。哇。因此,智慧總是在驅動,對嗎?

DJKR: Yes, has to be the driver.

仁波切: 是的,必須是司機。

DA: I love it. And then Rinpoche so I'm thinking…

丹尼爾: 我喜歡。然後,仁波切,所以我在想⋯⋯

DJKR: That's how you choose the name Wisdom Publications [Laughter]

仁波切: 這就是你選擇智慧出版社這個名字的原因(笑)。

DA: Yes. They chose a great name for that, actually. Wisdom is hopefully driving. Rinpoche, I'm thinking… you mentioned something: in the app you can actually—and I love this—you can click on a term and get more information and also bookmark passages. This is fantastic. I think you can even make your own notes. So, this is incredible. You can do your own chant and so make your own notes. And I'm thinking, this is fantastic. And Rinpoche, you mentioned a few things and you were saying that one thing you said was you were talking about this book you were reading, and the person said, ‘If only you knew Japanese,’ right? So that's one thing. So maybe this, and do you feel like that Rinpoche? Maybe here's a question: do you ever see the translations and, and see people practicing and then feel like, ‘oh, if only you knew the Tibetan, compassion is not the right word.’ Or something like that, we don't have this word. Do you feel like that sometimes, Rinpoche?

丹尼爾: 是的,他們選擇了一個偉大的名字,希望是智慧在駕駛。仁波切,您提到了在 APP 中,你可以點擊一個術語,獲得更多的解釋(我喜歡這個),還可以將段落收藏。這真是太棒了。你甚至可以做你自己的筆記 (譯:以後會有筆記功能) ,這真是不可思議。仁波切,您剛剛提到您正在讀一本書,而有個人說「如果你會日語就好了」,對嗎?對於這一點,會不會有這種情況:您看到翻譯,看到人們在修行,然後感覺「哦,如果你懂藏語就好了,慈悲這個詞翻譯得不對」。類似這樣,我們沒有這個詞。您有時會有這種感覺嗎,仁波切?

DJKR: You see, as I said earlier, I'm not a translator at all, so I cannot judge, but yes, there is that underlying sort of cautiousness always. But this is why at 84000, we deliberately don't want to rely only to so-called Buddhist practitioners: we want the academic world—those who sort of hold the banner of objectivity, whatever it means. It's good. It's really good. This critical thinking, analytical thinking, and, you know, really know this debating. First of all, argument is in the Indian DNA, the argumentative Indian, right? And Buddhism, coming from India is no exception. Buddhism has always started with argument, even in the texts, you know, so this, we need to keep it alive. And at 84000, being very aware of this, we have come to a conclusion that this whole translation is a work in progress. It's never going to end. And it's also because of language is evolving, isn't it?

仁波切: 你看,正如我之前說的,我根本不是一個譯者,所以我無法判斷。但是,是的,總是需要那種潛在的謹慎心。但這就是為什麼在 84000,我們故意不想只依靠所謂的佛教修行者,我們希望學術界來做。那些打著客觀性旗號的人,不管這意味著什麼,這很好,真的很好,這種批判性思維,分析性思維,以及,真正懂這種辯論的人。首先,辯論是印度人的 DNA,印度人善於辯論。來自印度的佛教也就不例外。佛教總是以爭論開始,甚至寫在了經文中,所以我們需要保持它的活力。在 84000,我們非常清楚這一點,我們得出一個結論,這整個翻譯是一項不斷進行的工作,它永遠不會結束。這也是因為語言在不斷發展,不是嗎?

DA: Yeah, that's true. So, we may need another round of translations in a hundred years’ time when everything's translated, then we need to go again. Rinpoche I'm wondering, which words do you think are first in line for a good argument?

丹尼爾: 是的,那是真的。所以,我們可能需要在一百年後再進行一輪翻譯,當所有的東西都翻譯完了,那麼我們就需要再去做一遍。仁波切,我想知道,您認為在一個好的辯論中使用最多的詞有哪些?

DJKR: Well, I don’t know, maybe I shouldn't be speaking like this, but anyway, I sometimes say that if I am the Kim Jong Un of Buddhism, I will ban words like ‘compassion.’

仁波切: 我不知道,也許我不應該這樣說話,但無論如何,我有時會說,如果我是佛教界的金正恩 (譯:獨裁者的意思) ,我將禁止像「慈悲」這樣的詞。

DA: So, tell us about that, Rinpoche. Why?

丹尼爾: 您能多說一下嗎,仁波切,為什麼?

DJKR: And ‘reincarnation.’ Because I think, okay… I'm very, very open for discussions and arguments, you know, another time, whatever, because many times, you know, the language always comes with a cultural tradition, etc., etc. So words like ‘reincarnation’—the English word ‘reincarnation’—maybe coming from a culture that believes in a ‘soul.’ A ‘soul’ that's going like this [waves arm]. That's not really what yangsi means, you know? So, there's a lot of that. And then also ‘compassion.’ It always rings this bell of some sort of a hierarchy: me the compassionate; and you, the sort of poor sentient being. That's not really what compassion is. I mean, if you want to know more about it, you should read like the homage—the very first stanza—of the Mādhyamikavatara by Chandrakirti, where he praised the compassion of everything. The first thing he praised was compassion. The object of compassion includes even the tenth bhūmi bodhisattava’s meditative state. So, what does this tell us? You see, it really tells us something to do with non-duality again, the driver, you see?

仁波切: 還有「轉世」這個詞。我願以非常非常開放的心態討論和辯論,因為很多時候,你知道,語言總是伴隨著文化傳統,等等等等。所以像英文的「轉世」這個詞,可能來自相信「靈魂」的文化背景。一個「靈魂」是像這樣的 (譯:仁波切揮動手臂,上上下下,表示生生死死) 。這並不是藏文「楊希」的真正含義,你知道嗎?有很多這樣的詞,包括「慈悲」,它總是敲響某種等級制度的鐘聲:我是慈悲的人;而你,是那種可憐的有情眾生。這並不是真正的慈悲。我的意思是,如果你想知道更多關於它的信息,你應該讀一讀月稱的《入中論》的皈敬頌(第一個偈頌),在那裡他讚揚了對萬物的慈悲,他稱讚的第一件事就是慈悲。慈悲的對象甚至包括十地菩薩的座上狀態。那麼,這告訴我們什麼呢?你看,它告訴了我們一些與非二元有關的事情。智慧又是司機,看到了嗎?

DA: Yeah, this is interesting. And that's maybe why it's good to be able to click on the word ‘compassion’ and get a little bit more of a flavor for what it is, or ‘reincarnation.’ And so, as you're reading these sūtras and you see that you can click and learn a little bit more about a word you might find, or it might be surprising for you and very informing. So that's a good thing to know.

丹尼爾: 是的,這很有趣。這也許就是為什麼點擊「慈悲」或者「輪迴」,就能對這個詞的意思有更多的了解,是多麼的好。當你在閱讀這些經文時,你可以點擊並了解更多關於這個詞的信息,它可能會讓你感到驚訝,並且很有啟發。這個功能真好。

DJKR: But by the way, I would still not discourage using the word ‘compassion’ for marketing strategy. All this is important. I know, but some people, like you—or probably me just because I have a labor—we are stakeholders here. So, we need to be aware of this. Otherwise in fifty years’ time ‘mindfulness’—the Buddhist mindfulness—Buddhist compassion, all this will become very mish-mash, everything will get mixed up. Then that is no-more Buddhism. Then it's like Tex-Mex. Yeah. Texan Mexican food is not really Mexican food.

仁波切: 但是,順便說一句,我仍然不會阻止大家使用「慈悲」這個詞作為營銷策略,這一切都很重要。有些人,比如你和我,只是因為我們有一個標籤,我們是利益相關者,所以我們需要意識到這一點,否則在五十年後,佛教的正念,佛教的慈悲,所有這些概念都會變得非常混雜,一切都會被混淆,那麼佛法就不再是佛法了。它就像德州墨西哥菜。是的,德州的墨西哥菜並不是真正的墨西哥菜。

DA: Not authentic. Yeah. I think ‘mindfulness’ is the word we can say. This has sort of happened to the word ‘mindfulness’ in a way.

丹尼爾: 不是正版的。是的,這在某種程度上已經發生在「正念」這個詞上。

DJKR: Please keep on using it though. It's really good marketing.

仁波切: 但請繼續使用它。這真的是很好的營銷。

DA: Yeah, marketing can be merit if wisdom is the driver, maybe! So, I'm thinking that technology… You mentioned before that some of the sūtras being carved in stone, and then we had paper, now we have websites and browsers and apps. And so, technology keeps changing. I think it's important that Buddhadharma doesn't change in a way—the truths of Buddhadharma I imagine—but we've got to keep updating the language as well so that the meaning comes through. So how do you think about when you're thinking like hundred-year plans, like some of the 84000's goals talk about seventy-five years, a hundred years: how do you plan for that type of thing?

丹尼爾: 是的,如果智慧是司機的話,營銷可以是有功德的!所以,我在想,您之前提到,有些經文是刻在石頭上的,然後我們有紙,現在我們有網站、瀏覽器和 APPS。因此,技術一直在變化。我認為重要的是,佛法在某種程度上不會改變(我想象中的佛法真理),但我們也必須不斷地更新語言,以使其含義得以體現。那麼,當您在考慮百年計劃時,您是如何考慮的?比如 84000 的一些目標談到了75 年、100 年,您是如何計劃這類事情的?

DJKR: Well, of course 84000’s task is to really translate the words of the Buddha as authentically and as accurately as possible. Beyond that we aspire teachers, students, thinkers… And actually I was listening to this Israeli professor Yuval Noah Harari. Yeah. And he was saying that the world leaders need to be philosophers, something like that. He said the big problem with the world leaders, they're all like lawyers—I'm sorry if there are some lawyers here, I don't mean it like that. Lawyers, engineers, businessmen. Yeah. They're fantastic. They are actually a tool to make the life work. Right. But philosophy is the one that defines what is life. Making life [work] properly or comfortably or working, that's the one thing. But defining life. So not just Buddhism actually, all philosophy, I think is now more important than ever, especially now. This is where us practitioners, students of Buddhadharma, we should really be aware of interpretations, therefore… again, back to tö sam—hearing, contemplation—and of course, practice… putting it into your practice. Even, you know, like the word gom, the practice. That really needs to be defined properly, because right now the moment the word gom is mentioned, immediately that Zafu comes with it.

仁波切: 當然,84000 的任務是真正地把佛陀的話語翻譯得儘可能真實和準確。除此之外,我們歡迎老師、學生、愛思考的人。實際上我正在聽以色列教授尤瓦爾·諾亞·哈拉里的演講。他說,世界領袖們需要成為哲學家,類似這樣的話。他說,世界領袖們的最大問題是,他們都像律師(如果這裡有一些律師,對不起,我不是貶義)。律師、工程師、商人,他們都很了不起,他們實際上是一種工具,讓我們的生活正常運轉。但哲學,哲學定義了什麼是生活。使生活正常和舒適是一回事,但定義生活則完全是另一回事。因此,實際上不僅僅是佛教,所有的哲學,現在比任何時候都更重要。這就是我們修行者,佛法的學生,我們應該真正意識到理解和聞思(再次提到)的重要性,然後,當然,把它們放到修行中去。甚至像禪修這個詞,真的需要被正確地定義,因為現在一提到禪修,馬上就會想到蒲團。

DJKR: That's wrong. You know it can even be on a hammock with a martini.

仁波切: 那是錯誤的。你知道修行甚至可以發生在吊床上,且喝著馬提尼酒的時候。

DA: So, Rinpoche, the philosopher king… We need the philosopher prime ministers and presidents maybe. And it seems that, you know, understanding… really having clarity about what you mean when you use certain words, is a part of that. You know, gom—meditation practice—what that actually means, seems really important. Rinpoche, when you teach, are you teaching by deconstructing words? Is that one of the ways you teach or how do you teach that? ‘Okay, you're used to this word, and this is what it automatically means for you, but let's deconstruct that.’

丹尼爾: 所以,仁波切,我們需要哲學家式的總理和總統。似乎我們在使用某些詞語時,真正清楚意思的,只是其中的一部分。禪修這個詞究竟意味著什麼,似乎真的很重要。仁波切,當您在教學時,您是通過解構詞語來教學嗎?這是您的教學方式之一嗎?您是如何教學的?是不是「OK,你已經習慣性使用這個詞,這就是它自動產生的含義,現在讓我們來解構它」這樣嗎?

DJKR: Very good. This is actually something that I am only recently beginning to do. I have actually recently told people that anything I have taught just about even up to two years ago, disqualify them all! It should be. Because I didn't understand. You know, when I meant, ‘nyingye’ I meant ‘tongnyi’… my words come out like, “compassion,” “emptiness.” I never paid any attention. For instance, people from Europe… these people have a background—they're not barbarians—they have lot of culture, they have an incredibly strong culture… For them, it [these words] means something else. And especially, I think—this is a joke I always make with many of my Western friends—that romantics, right, rationalism… Wow. If only the West met somebody like Chandrakirti because I think the West really loved reasoning, but they should have gone further. I feel that reasoning is also at the end of the day not perfect.

仁波切: 非常好的問題。這實際上是我最近才開始做的事情。實際上,我最近告訴人們,凡是我教過的東西,哪怕僅僅是兩年前的,請忘掉那些東西!應該這樣。因為我沒明白。當我腦子裡想的是(藏文)或(藏文)時,從我嘴裡說出來的話是「慈悲」和「空性」,我從來沒有注意到過。例如,來自歐洲的人(這些人有文化背景,他們不是未開化的人,他們有很多文化,有非常強大的文化),對他們來說,這些詞意味著別的東西。特別是,這是我經常和許多西方朋友開的一個玩笑,浪漫主義者們,理性主義者們,哇喔,如果能遇上像月稱這樣的人就好了 (譯:意思是月稱比西方理性主義更理性主義) 。因為西方人真的很喜歡理性,但他們可以走得更遠。我覺得最終理性也是不完美的。

DA: Go further than reasoning.

丹尼爾: 比理性更進一步。

DJKR: Yes. This is what the Prasaṅgika people do, right? They use other people's reasoning and defeat others.

仁波切: 是的,這就是中觀應成派的人所做的,不是嗎?他們利用別人的推理打敗別人。

DA: Beyond the mind, beyond reasoning. Nice. Rinpoche, I wanted to sort of finish with maybe one or two more questions. The way technology is going with AI and virtual reality, do you have any thoughts on what it might look like in ten, fifty years?

丹尼爾: 超越心,超越理性,太好了。仁波切,我想最後再問一兩個問題。關於人工智能和虛擬現實技術的發展,您對 10 年或 50 年後可能出現的情況有什麼看法嗎?

DJKR: I don't know so much about AI, but the little I have heard about AI and all of that, it's very encouraging, this is the best news for Buddhism! AI. Fantastic. I think. Because finally we will be forced to think, ‘What is vidya?’

仁波切: 我對人工智能瞭解得不多,但我聽到的關於人工智能等等等等的消息,非常令人鼓舞,這對佛教來說是最好的消息。我認為人工智能太棒了。因為最後我們將被迫思考,什麼是「覺」?

DA: Yes.

丹尼爾: 是的。

DJKR: I can't wait for AI to come faster because I think AI is probably the aspiration of a lot of the Buddhas and bodhisattvas, so to me, AI is like, wow. So good.

仁波切: 我迫不及待地想讓人工智能更快地到來。我認為人工智能可能是很多佛菩薩的發願。我對人工智能的感慨就是:「哇喔。這麼好!」

DA: We might find that what we thought was intelligence was actually all artificial… all artificial intelligence. Rather than prajñā, it’s all artificial intelligence maybe.

丹尼爾: 我們可能會發現,我們認為是智能的東西實際上都是人工智能。與其說是般若智慧,不如說是所有的人工智能。

DJKR: Exactly.

仁波切: 正是如此。

DA: You're actually very optimistic about this, AI and what we'll learn about what is the mind? That sort of thing, Rinpoche?

丹尼爾: 您對這些問題非常樂觀,人工智能,我們將學到的東西,如什麼是心?諸如此類的事情,仁波切?

DJKR: Yes. Actually again, the same guy I was listening to Yuval Noah Harari… He was talking about when there's too much AI and technological revolution, then there is a danger of a big, big chunk of society becoming useless. Suddenly, now, you are not a nurse anymore. You are not a postman anymore. Even my job, a rinpoche's job, a machine will do. So, who am I? Right?

仁波切: 是的。又要提到我在聽的尤瓦爾·諾亞·哈拉里的演講,他說,當有太多的人工智能和技術革命時,那麼就有一種風險是,社會的大大一部分突然變得無用。突然間,你不能再當護士了,你不能再當郵遞員了。甚至我的工作,一個仁波切的工作,機器也會做。那麼,我是誰?

DA: Yes.

丹尼爾: 是的。

DJKR: Buddhism teaches you how to appreciate the uselessness. So important, I think. Not to be afraid of uselessness. I mean actually, it's not even just Buddhism, some of the Eastern wisdom, like Taoism, even the concept of Wu wei or something like that, doing nothing. Wow. Now is the time to invoke all this, to appreciate this, to live with being useless. Because what is really ruining our life is really this notion of purpose of life. This idea of purpose of life has ruined us so much.

仁波切: 佛教教你如何去欣賞無用的東西。這是如此重要,不要害怕無用的東西。實際上,不僅僅是佛教,一些東方的智慧也是,比如道教的「無為」或類似的概念,「無為」就是什麼都不做。哇喔!現在是引入所有這些的時候了,欣賞這些,與無用的人一起生活。因為真正毀掉我們人生的,就是在乎「人生的使命」。這種人生的使命的觀念已經毀掉了我們這麼多。

DA: The meaning of life.

丹尼爾: 人生的意義。

DJKR: Yes.

仁波切: 對。

DA: So Rinpoche, we're coming to the end of the time of our conversation. Thank you so much. I know that you're teaching The Stem Array sūtra, a new sūtra on 84000. I think this Saturday. Did you want to talk, can you tell us a little bit about what that sūtra is?

丹尼爾: 所以,仁波切,我們的談話時間就要結束了。非常感謝您。我知道您要講授 84000 的新譯經文《華嚴經·入法界品》,好像是這個星期六。您可以談談嗎?您能告訴我們一點關於那部經的內容嗎?

DJKR: Okay. Before I end it, I'd like to thank Wisdom, actually you behave as if you are coming from outside, but you are one of us, 84000, you are very much involved. I must thank my big supporters, they've been so generous, and as I said, you know, translation work is not sexy. It's not like you see gold painted on the roof, so, where's the money going, you understand? The translators, my goodness, they have so much work and they do an incredible job. And then my administrators—I really mean it, my workers—they really do most of the work. I actually don't even know most of the time. And especially this time, I'd like to thank Brian and XMind, those who created the app. In the sūtras we read sentences, like Buddha manifests and then taught 10 thousand, twenty thousand, twenty million people, in one go.

仁波切: 好的。 在我結束之前,我想感謝智慧出版社,今天你表現得好像你是外部的人,但你其實是我們中的一員,84000 中的一員,你投入得非常深。我必須感謝我的大功德主們,他們一直很慷慨。正如我所說,翻譯工作並不性感,它不像在屋頂壁畫上塗金。他們看不到錢去哪兒了,這是個問題。這些譯者們,我的天啊,他們有這麼多的工作,他們的工作令人難以置信。然後我的管理員們,我說真的,我的工人們,他們做了大部分的工作,大部分時候我對這些一無所知。還有這一次,我想特別感謝 Brian 和 XMind 團隊,那些開發 APP 的人。在佛經中,我們經常能讀到世尊放光,然後一次給予一萬人、兩萬人、兩百萬人教法。

DJKR: And like in the past we used to [think], ‘okay, okay, only Buddha can do it.’ But it's quite close now, right? It's happening. So those prayers and those words are not just poetic only. Yes, I've been asked to sort of introduce [The Stem Array] of course, impossible to teach. I think that's what the last chapter of the Avatamsaka Sūtra, it alone has something like 800 pages. But I said ‘yes’ to the organizers that I will sort of speak about it, for just like maybe short one hour, because Avatamsaka Sūtra is really very much about the idea of infinite because you know people like you and me, we always use words like, ‘infinite’ ‘speechless’ ‘unthinkable’… ‘lots and lots and lots’ or ‘small, small, smallest.’ What do we mean by that? You know ‘infinite’ ‘unthinkable.’ So Avatamsaka is an incredible sūtra that is expressing the inexpressiblity. So, this is the part that I wanted to sort of just stir a little bit, but cannot explain.

仁波切: 而過去我們曾經認為「OK,OK,這是只有世尊才能做到的事」。但是,我們現在已經相當接近了,不是嗎?這一切正在發生。所以那些祈禱文和那些話不僅僅是文學手法。是的,我被要求介紹《入法界品》,當然不能說是教。我想這是《華嚴經》的最後一品,光是這一品就有大約 800 頁。但是我答應了組織者,我將某種程度上講講這部經,可能很短,也就一個小時左右,因為《華嚴經》跟「無限」的想法非常非常相關。你知道像你和我這樣的人,我們總是用這樣的詞,「無限」「不可言喻」「不可思議」「很多很多」或「最小最小」。我們這麼說是什麼意思?「無限」和「不可思議」是什麼意思?因此,《華嚴經》是一部不可思議的經,它言喻了不可言喻的東西。所以,這是我想稍微攪動一下的部分,但無法解釋。

DA: Thank you so much Rinpoche. So, Rinpoche, we're going to have a break now, and then we'll come back for the Q&A. And so I just wanted to thank Rinpoche, and on behalf of all of us at Wisdom, I'd like to congratulate everyone involved with 84000 for launching this app and making it freely for all. And so, we rejoice in this merit. And as we break, we're going to show a short video to officially launch the app. And we encourage everyone to download it from 84000.co forward slash mobile. We'll put the link in the chat. Okay. Rinpoche, thank you so much.

丹尼爾: 非常感謝仁波切。那麼,我們現在要休息一下,然後再回來進行問答。我謹在此感謝仁波切,並代表我們智慧出版社,祝賀參與發布 84000 APP 的每一個人,他們推出了這款 APP,並使其對所有人免費。我們隨喜你們的功德。在休息的時候,我們將播放一個簡短的視頻來正式推出這款 APP。我們鼓勵大家從 https://84000.co/mobile 下載它。我們會把連結放在聊天窗口中。好的。仁波切,非常感謝您!

宗薩欽哲仁波切,於 2021年10月27日 在線宣布 84000 App 正式上線,同時接受智慧出版社 CEO 丹尼爾的採訪。本文為上半部分。英文由智慧出版社提供。中文由 孙方 翻譯。