譯者按:頂禮本師釋迦牟尼佛!恕譯者才疏學淺,未明心要,謬誤在所難免,僅供參考。所譯文字未經上師認可,或專業翻譯機構校對,純以個人學習為目的,轉載或引用請慎重。

Fate, free will and karma

I begin with an expression of joy for being here and seeing many of my old friends. And also Happy Chinese New Year. I guess some people may think fate has brought you here. As a Buddhist, I don't know. I don't think we believe in fate, like something sort of predetermined. It does seem to have a connotation of being controlled from somewhere else. Something sort of supernatural, something beyond you. Then maybe some of you may think, well, it's your free will that brought you here. Again as a Buddhist, I don't know whether we believe in free will. Buddhists are really strange, because free will also seems to indicate that you can do things at your will i.e. you can do whatever you want. You have supremacy. You are supreme. Individual supremacy. I don’t know whether Buddhists believe in free will.

我首先要表達一下喜悅之情,因為在這裏見到了很多老朋友。也祝大家春節快樂。我想有些人可能會認為,是命運讓你來到這裏。作為一個佛教徒,我不認為我們相信命運,就像某種預先確定的東西,某種被控制的,超自然的東西,你無法掌控的東西。那麼,也許你們中的一些人可能會認為,好吧,是你的自由意志,把你帶到這裏。同樣,作為一個佛教徒,我不知道我們是否相信自由意志。佛教徒真的很奇怪,因為自由意志似乎也表明,你可以按照自己的意願做事,即你可以做任何你想做的事情,你有至高無上的地位,個人至高無上。我不知道佛教徒是否相信自由意志。

Well, Buddhists have an idea or notion of how to talk about this. We use the term “karma,” which is so overly used. I think it's in the English dictionary now, isn't it? At least it’s in Wikipedia, right? Actually, karma is simply a sort of law of cause, condition and effect. But fundamentally this karma is false. It is falsifiable. As logical and as sensible as karma might sound for some, it’s simply a law of cause, condition and effect. You plant marigold seeds. And then with fertilizer and the right conditions, the marigold will come. That's it. That's what it is. Karma. The law of karma. But as logical as it sounds, as sensible or even as empirical as might appear to be at times, karma is fundamentally falsifiable. Actually, even hardline Buddhists don't believe in karma. It's not like the Almighty Creator. It’s not an “almighty” thing.

嗯,佛教徒對如何談論這個問題有一個概念。我們用「業力」這個詞,這個詞用得太多了。現在連英文字典都有這個詞,不是嗎?至少維基百科有吧?其實,業力只是一種因緣果的法則。但從根本上講,業力這個概念是假的,是「可證偽」的(仁波切的意思是,業力從究竟意義上來說是不存在的,因此,若拿當今主流哲學界的「可證偽性」來衡量,對業力的定義完全可以描述成某種可證偽的論斷。而並非在此試圖證明「業力是門科學」)。雖然業力在某些人聽來很有邏輯,很有道理,但它只是一種因緣果的規律。你種下金盞花的種子,然後有肥料和合適的條件,金盞花就會開。就是這樣,這就是業力,業力就是這樣運轉的。但是,雖然聽起來很有邏輯,很有道理,甚至有時看起來是可感知的,可經驗的,但業力在根本上是可證偽的。其實,即使是強硬派的佛教徒也不迷信業力。它不是萬能的造物主,它不是任何「萬能」的東西。

Anyway, you're all here. And I'm sorry that there have been a few karmic consequences before I came. And those have had a lot of consequences for a lot of other people. It's quite amazing that just one person's change of movement could impact so many things, hotel rooms, air tickets — just so many things. But as I said, you are all here. Some of you are here because you're what we Buddhists call “karmically in debt”. I’m in debt with you and you are in debt with me. I mean, it’s fairly good proof that our karmic debt exists because some of you have been coming to me for the past 36 years. And if that is not proof that sycophants exist, then there is no other good proof.

總之,你們都來了。我很抱歉,在我來之前已經有一些業力顯現。而這些也給很多人帶來了很多後果。這是相當驚人的,只是一個人的行程變化就能影響到這麼多的事情,酒店房間,機票,這麼多的事情。但正如我所說,你們都在這裏。你們中的一些人之所以在這裏,是因為我們佛教徒所說的「業債」。我欠你們的債,你們也欠我的債。我的意思是,這是業債存在的相當好的證明。因為你們中的一些人在過去 36 年中一直來找我。如果這還不能證明馬屁精的存在,那就沒有其他更好的證據了。(眾笑)

You may have come here for many reasons. Perhaps curiosity, friends, or family somehow brought you here. Or maybe ads or word of mouth. And others among you may be mindfulness freaks or meditation freaks, and you just want to expand your knowledge about that and that's why you're here. Anyway, I guess you must have some sort of interest in what we call Buddhadharma, Buddhism, the Buddha’s way.

你可能因為很多原因來到這裏。也許是好奇心,也許是朋友或家人以某種方式把你帶到這裏,也可能是廣告或口碑效應。而你們當中的其他人,可能是正念的狂熱者或禪修的狂熱者(眾笑),你只是想擴展你對這方面的知識,這就是你來這裏的原因。總之,我想你一定對我們所說的佛法、佛教、佛法之道有某種興趣。

Projections of Buddhism have changed over time

In one way, Buddhism is really deep and vast and profound. But on the other hand, it’s also ridiculously simple. And this also makes it so difficult. It’s like a paradox. It's so difficult and at the same time it's so simple. This makes it so difficult. And probably it is a good thing. Maybe this is a self-defense mechanism of Buddhadharma or Buddhism. Maybe about two thousand years ago, Buddhism or so-called Buddhists would be considered in the way that we cherish or venerate or value or don’t value, I don't know, in the way that we look at computer scientists nowadays. Or astrophysicists or economists. That's how Buddhadharma, Buddhism or Buddhists were sort of looked at. I think there were different kinds of projections two thousand years ago.

從一方面來說,佛教真的很深奧,博大精深。但另一方面,它也簡單得可笑。而這也讓它變得如此的難。這就像一個悖論,它是如此困難,同時又是如此簡單。這讓事情變得很麻煩。也許這是件好事,也許這是佛法或佛教的一種自衛機制。也許在兩千年前,佛教或所謂的佛教徒,會以我們珍惜或尊崇或重視或不重視的方式被看待,我不知道,就像我們現在看待計算機科學家一樣,或天體物理學家,或經濟學家。佛法、佛教或佛教徒也算是這樣被看待的,兩千年前就有各種不同的投射。

And because of that, there were incredible patrons in India like the Pala Emperor Dharmapala. He funded or basically founded the famous Vikramashila University. So what I'm saying is that's how so-called Buddhism or Buddhists were projected upon or seen some two thousand years ago.

正因為如此,在印度有一些不可思議的護法,比如波羅王朝的皇帝達摩波羅。他資助了,或基本上說是創辦了著名的「超戒寺大學」,以應對另一所著名的大學「那爛陀大學」的衰敗。所以我要說的是,所謂的佛教在大約兩千年前就是這樣被投射或看到的。

Now, two thousand years later, this has changed. Now, if you look at a BBC talk show that has something to do with current religious affairs, where there are panel discussions about religion with all sorts of so-called religious pundits, then Buddhism is put together with Christianity, Judaism, Islam etc. into something called “religion”. Just imagine if in two thousand years, Sydney University gets categorized as “Oh, that temple, that cultish sort of temple”. Or if in two thousand years MIT, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, is seen as “Oh, those believers”. Maybe it won’t take even two thousand years. And what if future university professors are seen as no more than gurus - charming charismatic leaders? Something like that. That's how Buddhism has become, basically. The projections made upon Buddhism have changed a lot.

現在,兩千年後,這種情況已經發生了變化。現在,如果你看 BBC 的一個跟宗教時事有關的脫口秀節目,裏面有各種所謂的宗教專家對宗教進行小組討論,那麼佛教就會和基督教、猶太教、伊斯蘭教等放在一起,變成一個叫宗教的東西。試想一下,如果兩千年後,悉尼大學被歸類為「那是個寺廟」「那是個邪教的寺廟」。或者兩千年後,麻省理工學院的學員被看成「那些信徒」。也許連兩千年都用不上。如果未來的大學教授被視為不過是 Guru(上師),不過是迷人的魅力領袖呢?諸如此類,佛教就是這樣的,對佛教的投射已經發生了很大的變化。

There are many reasons for that. There are a lot of good reasons also. Many times, there's no choice. It's inevitable. Buddhists come with this Rinpoche gestures at his robes. Look, it looks really religious. Buddhists are always fiddling with flowers. They're always fiddling with things like incense. And they have gadgets like malas. So there’s all that. And Buddhism also has lots of stories. They tell stories about things such as the hell realm, hungry ghost realm, Sukhavati, Buddha realm, reincarnation. “You better behave, otherwise you'll be reborn as a prawn in your next life, and then you will end up being fried somewhere in Sichuan”. All these stories. So then you think, “Oh well”.

這裡有很多理由,也有很多很好的理由。很多時候,是別無選擇的,不可避免的。例如佛教徒穿著這個來(仁波切指着他的袍子),看起來真的很虔誠。佛教徒總是在擺弄鮮花(眾笑),他們總是在擺弄一些東西,比如香。他們還有像念珠這樣的小工具。同時,佛教徒也有很多故事。他們講的故事有地獄界、餓鬼界、西方極樂世界、佛界、轉世再生等。「你最好乖乖的,否則下輩子就會投胎成大蝦,然後在四川某個地方被油炸」(眾笑)。所有這些故事,你只能說「哦,好吧」。

But stories are important, really important. Let's say you’re a professor from Sydney University. You're a scientist. Really, you're a scientist through and through. And you're trying to explain a very important scientific concept to a kid or someone who has absolutely no background in science. But you have to do it, because it's your responsibility. But even more important, you feel. You care. You have compassion. You are a scientist with compassion. You are trying to cure a disease or you are trying to go to the moon or something like that. You do it with compassion, with care, with love. But how can you explain this scientific concept to a kid who has no background in science? How do you do it? You tell stories. Even scientists tell stories, don’t they? And that story might be written down by the student, typed, published, and five hundred years later someone reads it and thinks “Ah, it's a story”.

但故事是很重要的,真的很重要。假設你是悉尼大學的教授,你是個科學家什麼什麼的,你要向一個孩子,或者一個完全沒有科學背景的人,解釋一個非常重要的科學概念。但你必須這樣做,因為這是你的責任。更重要的是,因為你關心對方,你有慈悲心,你是一個有慈悲心的科學家。你正在嘗試治療一種疾病什麼的,或者你正在嘗試登上月球,或者類似的事情。你是帶着同情心,帶着慈悲心,帶着愛去做的。但你怎麼能向一個沒有科學背景的孩子解釋這個科學概念呢?你怎麼做呢?你講故事!即使是科學家也會講故事!不是嗎?而這個故事可能會被學生寫下來,打出來,發表出來,五百年後有人看了,只會覺得「啊,這是個傳說」。

Buddhism has interacted with other cultures

There are many other reasons why the projection of Buddhism is inevitably changing and has changed. After the birth of Buddhism in India, its host or birth country, it actually did not last long in India. But then it got adopted and nurtured and cradled by the Chinese for centuries. I think if you look at the number of Indian emperors who really supported Buddhism, maybe there were fifty, many fewer I think, maybe only twenty. But if you look at the list of Chinese emperors or kings who have supported Buddhism, it probably exceeds two hundred. Even today, China has more Buddhists than the rest of the world put together.

對佛教的投射,不可避免地已經發生了變化,並還在變化中,原因還有很多。佛教在它的出生地或宗主國印度誕生後,其實並沒有持續多久。但是後來它被中國人收留和養育了幾百年。我想如果你看真正支持佛教的印度皇帝的數量,可能有五十個,應該沒那麼多,我想可能只有二十個。但如果你看中國的支持佛教的皇帝或國王的名單,可能超過兩百人。即使在今天,中國的佛教徒也比世界上其它地方的佛教徒加起來還要多。

But when Buddhism traveled to China, China was not just some barren land. China already had its own culture, a really strong and deep culture that included Confucianism and Taoism. So when Buddhism came, the Confucianist culture had an influence on Buddhism and probably Buddhism also had an influence on Chinese culture. And this is very visible even today. Maybe the non Chinese may not understand this, but the Chinese people here would know. Many times among the Chinese, they will judge a so-called monk or nun or Buddhist, saying “Oh, he's a good Buddhist.” And if you ask why? Then they will give you a number of reasons one, two, three, four, five, something like that.

但是,當佛教傳到中國的時候,中國並不是什麼蠻荒之地,中國已經有了自己的文化,真正強大而深厚的文化,包括儒家和道家。所以佛教來的時候,儒家文化對佛教有影響,可能佛教對中國文化也有影響。而這一點即使在今天也是非常明顯的。也許非中國人可能不明白,但是在座的中國人都懂。在中國人看來,很多時候,他們會對一個所謂的比丘、比丘尼、佛教徒這樣評價:「他是個好佛教徒」。如果你問為什麼?他們就會給你一些理由,一二三四五,這樣的理由。

And most of these reasons are based on Confucianism for example, “Oh, because he really respects other people” or “Because he really takes care of older people,” That’s okay, but is Buddhism all about taking care of older people? Maybe not. That’s something to think about. I'm not saying that Buddhists say that you should not take care of older people. Buddhism is talking about something else. Not just taking care of old people or young people. Filial piety is not the most important thing for Buddhism.

而這些理由大多是基於儒家思想,比如「因為他真的很尊重別人」,或者 「因為他真的很照顧老年人」。這都沒問題,但佛教就是要照顧老年人嗎?也許不是。這是值得思考的問題。我沒有說佛教說你不應該照顧老年人,佛教講的是另外的東西,不僅僅是照顧老人或年輕人。孝順不是佛教最重要的東西。

Now, things have changed even in China. China has become a very materialistic society. This morning I asked a Chinese lady what is the word when somebody is lazy. When kids, it’s usually kids, are lazy and don't work, don’t clean the table, don't clean their room. When kids don’t do their homework, I heard that Chinese parents scold their kids by saying “you are becoming fo xi”, meaning “lazy". It's almost like laziness and not doing anything are synonymous with Buddhism. Actually the Australian Buddhists will understand this.

現在,即使在中國,情況也發生了變化。中國已經成為一個非常物質化的社會。今天早上我問一位中國女士,當有人懶惰的時候,那個詞叫什麼?通常是孩子們懶惰,不乾活,不收拾桌子,不收拾房間,不做作業的時候,聽說中國父母罵孩子的時候,會說「你變得佛系」,意思是懶惰。好像懶惰和不做事是佛教的代名詞一樣。其實澳洲的佛教徒會明白這個道理。(眾笑)

Buddhism is one of the oldest religions or philosophies or paths. It has really gone through a lot. You really need to know this.

一定要知道,佛教是最古老的宗教或哲學或道(隨便怎麼說)之一。它真的經歷了很多。你真的需要知道這些。

Language plays an important role

And language, wow, that is a really important one. Language plays a really important role. Okay, beware. Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche is known for making a lot of sweeping statements and generalizations. I totally admit it. A lot of sweeping statements. Why do I do that? Oh, you know, sometimes it's good to get attention. And also, fundamentally, I believe that people don't know how to communicate otherwise. Everybody makes sweeping statements, even including, “How are you?” “I’m fine”. That is a sweeping statement, but let's talk about that tomorrow when we talk about meditation. Everything is a sweeping statement. “Oh, you look good.” Which part?

而語言,哇,這是一個非常重要的因素。語言起着非常重要的作用。小心哦!宗薩欽哲仁波切真的因經常「一棍子打死很多人」而出名。這一點我完全認同,我確實有很多以偏概全的說法。 為什麼呢?你知道的,有時候引起注意是件好事。而且從根本上說,我覺得人們不知道如何溝通。其實每個人都會說以偏概全的話,甚至包括「你好嗎?」「我很好」,都是一個以偏概全的陳述。別急,讓我們明天談論禪修時再談這個問題。其實每句話都是以偏概全的陳述,例如「你看起來不錯。」「啊?哪一部分不錯?」(眾笑)

Language plays an important role in our life. Many of you here, those who are Caucasians, Westerners, Australians, New Zealanders, you speak English. And I'm trying to speak English here. My English is not good. I'm trying to speak English. Beware another sweeping statement. The English language has a lot of Abrahamic influence. Yes, maybe you are not a Christian. Maybe you're not a Muslim. Maybe you are not Jewish. But you do have Abrahamic habits. You do. I have met many pseudo-protestant Buddhists. So many. The world is full of them these days.

語言在我們的生活中扮演着重要的角色。在座的許多人,白人、西方人、澳大利亞人、新西蘭人(仁波切故意用鄉村口音),你們都說英語。而我在這裏也努力說英語。我的英語不好,但我在努力說。小心,這又是一個「一棍子打死很多人」的說法:英語受到了很多亞伯拉罕宗教的影響。也許你不是基督徒,也許你不是穆斯林,也許你不是猶太教徒,但你確實有亞伯拉罕宗教的習慣,確實有。我見過很多「偽新教佛教徒」,太多了,現在的世界充滿了這種人。

Language plays a really important role. You may not know it. You may not be conscious of it, but language has that influence. It’s deep and it's vast and, wow, it's not that easy to get rid off. When you say “good”, it will have an Abrahamic influence. It is quite different from the Sanskrit word “good”, the Pali word “good”, and the Tibetan word “good”. You understand? This is important to know. You need to know this.

語言起着非常重要的作用。你可能不知道,你可能沒有意識到這一點,但語言有這種影響。它很深很廣,而且,它不是那麼容易被擺脫的。當你說「好」的時候,它就會有一種亞伯拉罕式的影響。它跟梵語的「善」、巴利語的「善」、藏語的 「善」是完全不同的。明白嗎?這個很重要,你必須知道這個。

And by the way, you are not alone. This is true even for those who are not Caucasian, those who are not Westerners, such as let's say myself. I was born in Bhutan. Most Bhutanese, for one thing, they studied at schools with names like St. Helen’s, St. George’s, St. Joseph’s. Especially those who got education in colonial places, they have a strong Christian influence. So when an educated Bhutanese person in Bhutan says “good”, as in “good karma” or “bad karma”, “good this” or “good that”, we have to be very careful. What are they talking about? Because it's invisible, but at the same time it’s really important.

順便說一句,不止你們是這樣。即使對於那些不是白人的人,那些不是西方人的人,比如說我自己,也是如此。我出生在不丹,大多數不丹人,他們在聖海倫、聖喬治、聖約瑟夫這種名字的學校學習。尤其是那些在殖民地地方接受教育的人,他們受基督教的影響很大。所以在不丹,當受過教育的不丹人說「好」的時候,比如說 「善業」或「惡業」,「這個好」或「那個好」,我們要非常小心。他們在說什麼?因為它是無形的,但同時它又真的很重要。

Definitions of good and bad are becoming globalized and standardized

Plus, we now have Netflix. Game of Thrones. Wow. All those relentlessly establish the global meaning or globalized definition of the word “good”. The globalized meaning of “bad”. It happens. Recently I was talking to a Chinese mother who has a small kid, and he wanted a dragon. Wow. The dragon is such an important thing for the Chinese isn't it? It's everywhere. But when I showed this kid a Chinese traditional dragon, he couldn't understand what that is. He wanted the Disney version of the dragon. Things change so much, don’t they?

此外,我們現在有 Netflix,有「權力的遊戲」。哇哦,所有這些無情地確立了「好」字的全球化定義,「壞 」字的全球化定義。這是正在發生的。最近我和一個中國媽媽聊天,她的小孩想要一條龍。龍對中國人來說是多麼重要的東西,不是嗎?它無處不在。但是當我給這個孩子看中國傳統的龍的時候,他不明白那是什麼。他要的是迪士尼版的龍。世界完全不同了,不是嗎?

Yes, the globalized, standardized meaning of good and bad. That's also happening. And this has a lot of impact by the way, and things are changing so much. For instance, just now before I came here, I met one of my Australian friends and there was a momentary dilemma because she lost quite a lot of weight. In places like Bhutan, the response is, "Are you okay?” Because you have lost so much weight. You know, in places like Bhutan when you are a little bit chubby, voluptuous, big, then you are healthy. But now that has changed. So, to have lost weight is actually good.

是的,善惡的意義正在被全球化、標准化,這正在發生。事情的變化太大了。順便說一下,剛才我來之前,遇到我的一個澳大利亞朋友,一時之間我陷入了困惑,因為她瘦了很多,減重了很多。在不丹這樣的地方,人們的第一反應一定是:「你還好嗎?」。因為你已經瘦了這麼多。你知道,在不丹這樣的地方,當你有點胖,豐滿,大塊頭,那麼你就是健康的。但現在這種情況已經改變了。所以,瘦了其實是「好」。

So the definitions of good and bad have changed. So all these changes, how we validate values, how we define the meaning of meaning. Basically, it really changes how you project. How you see your life in general. It does. I think it really does have an impact. For example, maybe you are one of those people who grew up watching “The Simpsons” or “Tom and Jerry”. In “Tom and Jerry” there is a lot of smashing, isn't there? A lot of smashing and things falling. Have you thought about it? They never go naked or have sex, Tom and Jerry, or with others. But they smash a lot. The reason why I'm telling you this is that violence is sort of okay, but nudity? No, not during that time. Not with Tom and Jerry. Tom and Jerry having sex? That's sacrilegious. If you grow up in this kind of culture and in this kind of environment, then of course it has an impact on your value system, the way you define your values, the way you see things.

所有這些變化,使得我們如何驗證價值觀,如何定義「意義」的意義。基本上,它真的改變了你如何投射,你如何看待你的生活。它確實如此,我認為它真的有影響。例如,也許你是那些看着「辛普森一家」或「湯姆和傑瑞(貓和老鼠)」長大的人之一。在 「湯姆和傑瑞」中,大家都在砸東西,不是嗎?拼命打架,東西被打得粉碎。可是你們想過嗎?他們從來沒有裸體,或做愛,湯姆和傑瑞做愛,或跟其他人做愛?(眾笑)我的意思是,暴力是可以的,但是裸體,不可以。湯姆和傑瑞做愛?不,那是褻瀆神靈的!如果你在這樣的文化中長大,在這樣的環境中長大,當然會影響到你的價值體系,你對自身價值的定義方式。

The importance of being open-minded

Anyway, I'm saying all this because we’re supposed to talk about the Buddhist view, Buddhist meditation and Buddhist action. I'm saying these things because hopefully, I mean ideally, you have to be open-minded. Really open-minded. But that's difficult, really difficult. Being open-minded is not our character, not in the human character. You know, I have so many hippie friends in Australia. Sadly, they're getting a little extinct, and there are no lineage holders. Why is that? Maybe I'm going to the wrong places, but there are not many lineage holders. In any case the hippies pride themselves for being open minded, but actually they’re very conservative. Yes, they’re so fanatical, actually. They believe in certain values just so much.

總之,我之所以說這些,是因為我們應該談的是佛教的見地,佛教的禪修,和佛教的行動。我說這些事情是為了,理想的情況下,你必須要有開放的心態,真正的開放心胸。但這很難,真的很難。心胸開放不是我們的性格,不是人類的性格。你知道,我在澳大利亞有很多嬉皮士朋友。遺憾的是,他們有點絕迹了,沒有傳承持有人(眾笑)。為什麼會這樣?也許別的地方不是這樣,但總的來說缺乏傳承持有人。無論如何,嬉皮士們自詡為思想開放的,但其實他們很保守。是的,他們是如此狂熱,他們對某些價值觀就是這麼迷信。

Anyway, it would be good to be open-minded if you can. But if you cannot, that's fine. At least you need to know the importance of language, not only during this time, but throughout your study of wisdom traditions from other cultures. I mean, if you are studying any kind of Indian wisdom tradition or Asian wisdom tradition, or one based on Latin, whatever. Language is always going to be a challenge. So I think it's always important to accept that reality.

總之,如果你能做到心胸開闊就好。但如果你不能,也沒關係。至少你要知道語言的重要性,不僅這一次,而且在你學習其他文化的智慧傳統的整個過程中都要知道。我的意思是,如果你正在研究任何一種印度智慧傳統或亞洲智慧傳統,或者基於拉丁語的智慧傳統,不管是什麼。語言總是會成為一種挑戰。所以我認為接受這個現實總是很重要的。

As I said earlier, many of you have Abrahamic influences. Whether consciously or unconsciously, it doesn't matter. But you have that Abrahamic habitual pattern. And the Abrahamic system is a dualistic system. They're proud that they're dualistic. Evil versus good. Right versus wrong. The Abrahamic system is is very dualistic. They're proud of this. It's very clear actually. It's also more directional. I think it's really good for giving directions, “Okay, do it this way”.

就像我前面說的,你們中的很多人都受到了亞伯拉罕宗教的影響。不管是有意識的還是無意識,這都不重要。但你們有那個亞伯拉罕宗教的習氣模式。而亞伯拉罕體系是一個二元對立的體系,他們以自己是二元對立的為榮。惡與善,對與錯,亞伯拉罕系統是非常二元對立的。他們以此為榮,他們有很清楚的方向性,很適合給人指明方向:「好吧,向這個方向去做」。

Buddhism is not really dualistic. It's a non-dualistic system. So if you have a language, habit, culture that has a strong duality or dualistic thinking approach, and then you use that language, that tool, to understand a nondual system, it’s going to be difficult. But I think to have that in your mind as a study tool will probably help.

而佛法不是二元對立的,而是一個「非二元」的系統。所以,如果你的語言、習慣、文化有很強的二元性,或二元對立的思維方式,然後你用這種語言、這種工具去理解一個非二元論的系統,那就會變得很困難。所以我想,在你的腦海中記住這一點,作為一個學習工具,可能會有幫助。

So our subject is view, meditation and action. Actually, I'm going to add one more: View, meditation, action and result.

好。我們的主題是見、修、行。其實,我還要補充一個,應該是:見地,禪修,行動,和結果。

Result

I'm going to talk about the result first and be done with it, and then we will not talk about it further. What is it? What is the profit? What is the aim, the purpose, the result of the Buddhist path? I will go through these all one after another, but first just a brief summary. Fundamentally, the Buddhist result has got nothing to do with “something to get”. You must write this in bold. It’s very important.

我先把「果」談完,後面我們就不再提了。什麼是果呢?法道的利益、目的、宗旨、結果是什麼?這些我都會慢慢來,但首先只是簡單的總結。從根本上說,佛法修行的結果與「有所得」毫無一丁點關係。這一點你一定要用大字寫下來!這是非常重要的。

The Buddhist result has got nothing to do with “getting” or “attaining” or “achieving” enlightenment. Yes, we say this a lot e.g. to “achieve enlightenment”. We use these kind of phrases and language and examples. But remember how I was talking about stories? Fundamentally the Buddhist idea of result is not defined by what you get or obtain. Rather, it’s defined by what you get rid of.

佛法的果與「得到證悟」或「達到證悟」或「實現證悟」無關。是的,我們經常這樣說,我們用這些短語、語言和例子。但是,還記得前面談到的故事嗎?從根本上說,佛教的果的含義不是由你得到或獲得什麼來定義的,而是由你擺脫什麼來定義的。

And it's because of this that we have the word “Buddha”. It has the connotation of “awakened”, which is about dispelling sleep. To awaken is to get rid of sleep. So, to be awakened. That's really important. That’s what Buddhism, Buddhadharma, is aiming for. To get rid of. To be awakened. To get rid of what? To get rid of mistaken ideas, false ideas, delusions. Yes, that is the quintessential meaning of the word “nirvana”. That's it in terms of the result, because it’s important that we dwell on the other three. View, meditation and action.

也正因為如此,我們才有了「佛」這個字,它有「覺醒」的內涵,就是要祛除睡眠。覺醒就是祛除睡眠,這真的很重要。這就是佛教和佛法所要達到的目的:要擺脫,或者要覺醒。擺脫什麼?擺脫錯誤的觀念、錯誤的想法、妄想。這就是「涅槃」二字的精義。果講完了,現在我們要安住在其他三個方面:見、修、行。

Our aim is to not have any view

At a glance, when we talk about view, it might seem that we’re talking about what Buddhists believe. The Buddhist view, the Buddhist belief. But this is really difficult, because ironically Buddhism, the whole Buddhist path, is really trying in so many ways to get rid of all kinds of beliefs. The aim is to not have any view. To shrug off all views. To do without any view. Because view is a problem. Fundamentally Buddhists don't like to have a belief. I think you need to know that. So in other words, fundamentally the Buddhist aim is not to have any view. So why do we talk about view? To explain this we have to talk about the history of the path. How does a path emerge? When did it start? How? Why is there a path, a way, a religion, a system? Why? It's actually very simple.

乍一看,我們說到見地,似乎是在說佛教徒相信什麼,佛教的見地就是佛教的信仰。但這真的很難,因為諷刺的是,佛教,整個法道,真的是在用盡方法來擺脫各種信仰。沒有任何見地才是我們的目標。要甩掉所有的見地,要沒有見地地去做事,因為有見地就意味著有問題。從根本上說,佛教徒不喜歡有信仰,你需要知道這一點。所以,從根本上講,佛教的目的是不要有任何見地。那麼我們為什麼要談見地呢?要解釋這個問題,我們必須要談法道的歷史,一條法道是如何出現的?什麼時候開始的?怎麼出現的?為什麼要有一條法道、一種方式、一種宗教、一種制度?為什麼會出現?其實很簡單。

Because we have mind, this is why. I don't know how to put this. You have a mind. And you can never, ever take leave from this mind even for a weekend. Forget a weekend. You can’t even do without it, you can’t pause the mind even for a few moments. Maybe if you faint, or they say if you're in a coma but that's very debatable, or a deep sleep, or a startled moment and so forth. But let's not get too technical.

因為我們有心,這就是原因。你有心,我不知道該怎麼形容。你永遠,永遠不能離開這個心,哪怕是一個周末。別說一個周末,你甚至不能暫停它哪怕是幾分鐘。如果你暈倒了,或者說如果你昏迷了(這是非常值得商榷的),或者深度睡眠,或者一驚一乍等等,但我們不要談這些技術細節。

You have a mind. Is it fortunate that you have a mind? Yes. But it's also very unfortunate that you have a mind. Don't you wish that you were a table? It doesn't have a mind. So it really doesn't care whether anybody is using it as a table or not. It never feels rejected. It never asks itself, “Do I look good? Do I smell good? Am I am I strong?” Nothing.

你有心,有心是件幸運的事嗎?是的,但有心同時也是件很不幸的事。你從來沒有想過當一張桌子嗎?它沒有心,因此它真的不在乎是否有人把它當桌子用,它從不覺得自己被拒絕。它從不問自己:「我好看嗎?我的氣味好聞嗎?我是不是很強壯?」什麼都不問。

But we do. We have this thing called mind, and it always ends up knowing things. It always ends up cognizing things. No matter how much you try. The more you try to not cognize, the more it ends up cognizing. You end up being aware of things. And if it were just a simple awareness, simple cognition, simple knowing - that would have been so much better. But it’s not like that. After cognition comes assessing value, creating meaning, good and bad. All that. And then this leads to hope, fear, expectations. The whole war begins with this.

但我們會。我們有這個叫心的東西,它總是知道一些事情,它總是能認知事物。不管你怎麼努力,你越是想不認知,它就越是認知,你最終總會意識到一些事情。如果它只是一個簡單的意識,簡單的認知,簡單的知道,那會好得多。但事實並非如此,認知之後是評估價值,創造意義,好的,壞的,所有這些,然後這導致了希望、恐懼、期望。整個世界大戰就是從這裡開始的。

Because you have this mind. You have this. This is not a mystery. I'm not talking about some mythical or mystical mystery. You have it. You are listening to me right now. You are noticing a baby crying now. This. This thing that you have. The thing that imagines. The thing that gets fidgety. The thing that gets annoyed. The thing that sometimes gets inspired. And you know mind, it's so unpredictable.

因為你有心,你有這個東西。這不是什麼神秘的東西,我不是在說什麼神話或神祕的奧祕。你擁有心,你的心現在正在聽我說話,你現在注意到一個嬰兒在哭。那個會想象的東西,那個會坐立不安的東西,那個會煩躁的東西,那個有時會有靈感的東西,就是心,它是如此的不可預知。

Hallucinogenic substances, a horn and a tail

You have that. And not only do you have a mind, but also the mind always ends up creating different views. I'm talking about why we need the Buddhist view. And I already told you that actually the final aim of Buddhism is to not have any views. But at the same time, we need to talk about the Buddhist view.

你有這樣的心。不僅你有心,而且心最後總是會產生這樣那樣的見地。我正在說的是,為什麼我們需要佛法的見地。我已經告訴你了,其實佛法的最終目的是沒有任何見地。但同時,我們也需要談佛法的見地。

Why? It's like this. Australians are quite familiar with this. Let's say you took a hallucinogenic substance. You took something hallucinogenic. And you now think you have a horn and you have a tail and you're thinking, “Oh my goodness. How do I go to my job tomorrow? How do I meet my girlfriend or boyfriend? Where do I hide my tail?” You have all this panic.

為什麼這麼說?澳大利亞人對這個很熟悉。假設你服用了一種致幻物質(眾笑)。你服用了一些致幻劑,現在,你認為你的頭上長了角,身後有一條尾巴,你在想「上帝啊,我明天怎麼去上班?」「我怎麼去見我的女朋友或男朋友?」「尾巴要藏到哪裡去?」你有所有這些恐慌。

And what do I say to you? Even if I say, “Oh, don't worry,” that's so patronizing. Actually, I shouldn't even be saying anything about your horn, because you don't have a horn. You don't have a tail. Even to say, “Don't worry”, even that is an instruction. “Don't worry. Calm down”. Oh my goodness, that’s getting worse. “Calm down. It's okay. Don't worry”. But all this doesn't help. You have to add more i.e. you need to do more things to help the other person who is worrying about their nonexistent horn. So you say “Drink more water”, right? Drink more water. You pet somebody. Caress. Hug. All that helps. Helps what? It helps you to be relieved from the anxiety caused by this non-existing horn and this non-existing tail.

那我該怎麼跟你說呢?就算我說「別擔心」也都太清高了。其實,我根本不應該談論你的角,因為你沒有角,你沒有尾巴。即使說「別擔心」也是一種教授。即使說「冷靜下來」或者「沒事的」,天哪!越來越糟糕!冷靜下來、沒事的、不要擔心,這些都無濟於事。你要做更多,例如說「多喝熱水」,例如撫摸,例如擁抱。你需要做更多才能幫助到一個人,幫助什麼?幫助他從並不存在的角和並不存在的尾巴所引起的焦慮中解脫出來。

I still need to tell you some sort of a view, as in "It's okay. Don't worry”. It would be worse if the hallucinogenic mushroom-taker is not an experienced one. You know, someone who is not a disciple of superior faculties14. If he is not, it would be worse. He might be in denial that his own hallucination is not real. If you were to say “What do you mean by horn? What do you mean by tail? I don't see it. Come on, don't kid yourself. Don't deceive yourself.” That's the worst kind of instruction that you can give. In fact, if you are a good friend, a good companion, someone compassionate, kind and caring, you almost have to say “Yes. Let me get a new tailor for you. Probably we could find a way to hide your tail”. You have to entertain him by acknowledging his hallucination experience, you have to sort of get along with this friend of yours.

所以,到頭來我還是要給出一些見地,其實就是「沒事的,別擔心」。如果吃了致幻蘑菇的人不是一個有經驗的人,那就更糟糕了。你知道,如果不是一位卓越的上師的弟子(仁波切有點諷刺的口氣),那就更糟糕了。他可能是在否認自己的幻覺不是真實的。如果你說「什麼叫角?什麼叫尾巴?我沒看出來。拜託,別自欺欺人了。」這是你能給的最差的一種教授。其實,如果你是一個好朋友、好夥伴,一個慈悲、善良、有愛心的人,你幾乎會說這樣的話:「好啊,讓我給你找一個新的裁縫。也許我們可以找到一個方法來隱藏你的尾巴。」(眾笑)你要通過承認他的幻覺經歷來娛樂他,你要和你的這個朋友好好相處。

And that's what I have to do for these three days. Not that I myself am not dreaming like this. I am, very much. But I have I have read about it more than you have. So I have a much more sophisticated tail. And this sophisticated tail is much more difficult to get rid of than your blob, that tail that you have. Actually it’s true. Should we take a break? Yes, I think we should take a break.

而我這三天要做的就是這個(鼓掌)。不是說我自己不做這樣的夢,我非常是這樣的人。但我比你讀過的這類書多。所以我的尾巴要復雜得多,比你的那個尾巴更難擺脫。這是真的。我們要不要休息一下?是的,我認為我們應該休息一下。

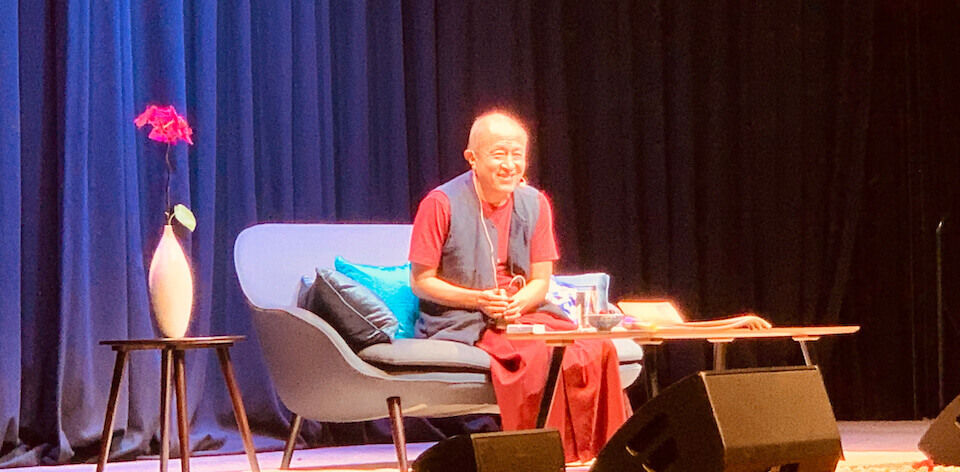

宗薩欽哲仁波切,於 2020年1月25-27日(農曆新年)在澳大利亞悉尼的新南威爾士大學,給予了為期三天的教授,題目為《見修行》。英文部分由 Alex Li Trisoglio(仁波切指定的佛法老師)聽寫,並分段和添加標題,發布在 Madhyamaka.com。中文部分由 孫方 翻譯。並在翻譯過程中,根據視頻做了文字上的修訂,所以中英文部分可能會有可忽略不計的微小差別。照片為課程現場。