譯者按:頂禮本師釋迦牟尼佛!恕譯者才疏學淺,未明心要,謬誤在所難免,僅供參考。所譯文字未經上師認可,或專業翻譯機構校對,純以個人學習為目的,轉載或引用請慎重。

What do Buddhists believe?

So we are talking about the Buddhist view. Suppose you ask a Buddhist “What is it that Buddhists believe in? Do Buddhists believe in karma?” “Mmmm, Yes” DJKR answers his own question with an uncertain tone and manner that indicates he doesn’t fully disagree, but he doesn’t fully agree either. “Do Buddhists believe in doing good things?” “Yes” DJKR answers with the same hesitant and uncertain tone and manner. I'm sort of demonstrating the inner attitude to the view. It’s like this. “Do Buddhists believe in hell realms?” “Yes.” “God realms?” “Yes.” It's a bit like this.

我們正在談的是佛教的見地,即佛教徒相信什麼?佛教徒相信因果報應嗎?嗯~~,是的。佛教徒相信我們應該去做善事嗎?嗯~~,是的。我算是表明了內心對這個觀點的態度。佛教徒相信有地獄嗎?是的。有天堂嗎?是的。有點兒像這樣。(譯:這幾個問題,仁波切都在用非常猶豫的語氣回答,說明他沒有完全不同意,但也沒有完全同意。)

“Come on, be serious. You must have a belief. What is it?” So you're squeezing the other person now. This is what the Buddhists would think or say. They will say, “If you have a wrong view, a partial view, an incomplete view, or a lopsided view, you will suffer”. That much they will say, “If you have a wrong view, that will lead you to disappointment”. This much I’m quite sure they will say. But even that, a very seasoned Buddhist will say that only very reluctantly. Now we're talking about a very fine-tuned version of the Buddhist view.

「行了,認真點。你一定有一個信念,是什麼呢?」如果你非要擠牙膏,佛教徒會這麼認為,或這麼說:「我們相信,如果你有錯誤的看法,有偏頗的看法,有不完整的看法,有片面的看法,你就會痛苦。」明白了嗎?「如果你有一個錯誤的觀點,你就會失望。」我很肯定他們會這麼說,但即使是這樣,這仍然只是一個很有經驗的佛教徒,在很不情願的情況下說的。你看,我們在說的是一個非常細化的佛教見地。

Because of that, Shantideva said, “Buddhists can have one ignorance for the time being. But only for the time being. And what is that? To think that there is enlightenment.” This really sums up the Buddhist attitude towards the view. Shantideva was one of the greatest commentators from Nalanda University. And if you were to ask him “Why am I permitted to have that ignorance, to think that there is enlightenment?” He would answer “Because I see that you are in pain. You are suffering. You have anxiety. You are not satisfied. That's why. You have to sort of shrug it off. You have to come out from that pain and the cause of that pain. That's why”. This is a very important statement.

正因為如此,寂天菩薩說:「佛教徒可以暫時有一個無明,但僅僅是暫時的。那是什麼呢?就是:認為有一個東西叫做證悟」。這確實概括了佛教對見地的態度。寂天是那爛陀大學最偉大的釋論作者之一。如果你要問他 「為什麼?為什麼允許我有那種無明,認為有證悟存在?」他會回答:「因為我看到你在痛苦中。」你有痛苦,你有焦慮,你不滿足,這就是為什麼。你要甩開它,你要從那種痛苦和痛苦的因中走出來,這就是為什麼。這是一個很重要的表述。

Falling from a cliff and hanging onto a branch with your teeth

Let’s articulate this further. To begin with, imagine you have fallen from a cliff. Your hands are tied. And you just managed to grab a branch on the cliff face with your teeth. And somebody is walking above you on the clifftop. You see them and now what do you do? You can’t shout for help because the moment you say “Help”, you have fallen. It’s a bit like this. If you wish to teach the Buddhist view, the moment you speak, you make mistakes.

讓我們進一步闡述一下。首先,想象一下你快要從懸崖上掉下來,並且你的手被綁住了,而你剛剛成功地抓住了懸崖上的一根樹枝,是用你的牙齒咬住。此時,有人在你上方的崖頂上行走,你看到他們,現在你該怎麼辦?你不能大喊救命,因為當你說「救命」的那一刻,你已經掉下去了。如果你想教授佛法的見地,就有點像這樣,你一說話就會犯錯。

And by the way, this is what Siddhartha Gautama said after his so-called enlightenment. As he awakened to that state, he actually said, “I have found a brilliant, profound, vast, uncompounded truth. But no one would hear it.” But then the story is that his disciples Brahma and Indra came and requested him to teach. And when they requested this, they told him “There are so many beings who are tormented by suffering caused by delusions. So through your great compassion and wisdom and skillful means, please liberate them step by step in different ways, with different means”. And that's supposedly how the Buddha began teaching the Dharma. He started in a place called Sarnath which is near Varanasi.

順便說一下,這就是悉達多喬達摩在所謂的證悟之後說的話,當他覺醒到這種狀態時,他居然說:「我發現了一個輝煌的、深奧的、廣大的、非和合的真理。但是沒有人願意聽。」之後的故事是,他的弟子梵天和因陀羅前來,請求他教授。他們請求的時候,就告訴他:「有那麼多的眾生,被妄想所造成的痛苦所折磨。所以請您通過您的大悲心、智慧、和方便,用不同的方式、不同的方法,一步一步地使他們解脫」。歷史上,佛陀應該就是這樣開始教授佛法的,在瓦拉納西附近一個叫鹿野苑的地方開始的。

In other words, he was trying to articulate something that cannot be articulated.

換句話說,他是想表達一些不能表達的東西。

In the Buddhist philosophical system, Buddhists invented a certain discipline or a certain structure to understand this view that cannot be articulated. And actually they invented many structures. I think this time we will try to use the approach that we call the “two truths”. Many of you know this. I see a lot of old Buddhists here, those who have gone to many of my own teachings, not to mention many other teachings. For many of you, this will be very familiar and probably you are even jaded with this information, after hearing it again and again. But on the other hand, it is always important. It's always refreshing and it’s a reminder. It can help.

在佛教的哲學體系中,佛教徒發明了某種學科或某種結構,來理解這種無法表達的見地,實際上他們發明了很多結構。我想這次我們會嘗試用我們所說的「二諦」的方法。很多人都知道這個道理,我在這裏看到很多老佛教徒,他們聽過很多我自己的教授,更不用說很多其他人的教授。所以,對於你們很多人來說,這將是非常熟悉的,可能你們甚至對這些信息已經厭倦了,聽了一遍又一遍。但另一方面,它總是很重要,它總是令人耳目一新,它是一種提醒,它可以幫助你。

Hallucinogenic substances, a horn and a tail

And this time I'm going to use the horn and the tail example a little bit, so that you can comprehend what I'm talking about. Now, let's say you have taken this pill or mushroom or whatever, and then you have the horn experience and the tail experience.

而這次我還要用角和尾巴的例子來說明一下,這樣你就可以理解我在說什麼。現在,我們假設你嗑了藥丸或者迷幻蘑菇什麼的,然後你正在體驗你長了角和尾巴。

And let's say you're really going through panic. You're really paranoid. Panic. Anxiety. It's not right. It's not nice to have a horn. It's not nice to have a tail. Especially when there are a lot of things at stake. You have a lot of things to do and agendas. And the more plans that you have, the more that the horn and the tail are going to bother you. If you don't have many plans, it doesn't really matter if you have a horn and a tail.

假設你真的經歷了恐慌,你真的產生了妄想,恐慌,焦慮。「這不正常,有一個角是不好的,有尾巴也不好。」特別是當有很多急事的時候,你有很多事情要做,有很多議程。而你的計劃越多,角和尾巴就越會讓你煩惱。如果你的計劃不多,那你也無所謂。

Let's say you just took that pill and you have really forgotten the fact that you don't have a horn. You forgot. You know, the pill is strong. When the effect of the substance hits you, you really forget this truth that you actually don't have a horn and a tail. I don't know whether you you can relate to this. Yes, many Australians would. You just forgot. You’re very much into this panic and anxiety about having a horn and a tail. Your hands are sweating.

比方說,你剛嗑了藥,你真的「忘記」了你沒有角的事實,是「忘記」。因為藥丸的藥效很強,當這種物質作用到你身上的時候,你真的忘記了這個事實,你其實沒有角和尾巴。我不知道你們是否能體會到這一點,澳大利亞人應該都會(眾笑)。你非常沈浸於這種關於角和尾巴的恐慌和焦慮中,你的手心都出汗了。

The truth can be realized without language

Now this is important. Suppose that suddenly a gust of wind blows and the window bangs. Or there’s a sound of someone flushing the toilet. Or your phone rings. DJKR slaps his hand. This takes you to reality. “Oh, the phone is ringing. This is not too bad. Maybe this is not true.” You understand? Coming back to the real truth. Because the phone rings. You touch behind you, “Yes, no tail”. But then you still feel the tail because the impact of the pill or mushroom is still there. But then you think, “Maybe it's not happening”.

然後,很重要的是,假設突然一陣風吹來,你聽到窗戶砰砰作響的聲音,或者有人沖廁所的聲音,或者你的電話響了。(仁波切突然拍手)這就把你帶到了現實中。「哦,電話響了,這還不算太壞,也許這不是真的。」你回到現實中來,你摸了摸身後,是的,沒有尾巴。但後來你還是感覺到了尾巴,因為藥丸或迷幻蘑菇的影響還在。但你又想,也許這不是真的。

No words and no language are necessary. This happened just through the ringing of a phone or a window banging. Or more likely your wife or husband or dog just came in. And that made you realize you don't actually have a horn and tail. I'm talking about something quite exotic in a way. I'm talking about so-called “blessing”. We will not talk about this too much here, because it's not really the time.

不需要任何語言,只是通過電話鈴聲或窗戶的敲擊就會發生,或者更可能是你的妻子或丈夫或狗剛進來,這讓你意識到你其實並沒有角和尾巴。我是在以某種神奇的方式說,但我說的是其實是所謂的「加持」。你們肯定聽過這個詞,我們在這裏就不多說了,因為現在真的不是時候。

What I'm talking about is the view, the truth. And to realize this truth, actually, there are some amazing ways. But to really appreciate these amazing ways, or the amazing coincidence, or the amazing incredible cause and condition, you need to be sober. At least partially sober. You need to be sort of daring. You need to be critical and at the same time receptive.

我真正在說的是見地,是實相。而要證得這個實相,其實是有一些神奇的方法的。但要真正領悟這些神奇的方法,或者說神奇的巧合,或者說神奇的不可思議的因緣,你需要保持清醒,至少是部分清醒,你需要有點大膽,你需要有批判性,與此同時,又需要有接受性。

So in Buddhism, we hear stories like Tilopa just hitting Naropa’s head. That's it. He gets it. But that’s Tantra, so let’s not talk about it as Tantra is too risky these days. So let's not talk about this. But even in the Mahayana there's a story about how the Buddha picked up a lotus and looked at it and smiled, and guys like Kashyapa get it. What does he get?

所以在佛教中,我們聽到的故事,例如帝洛巴只是打了那洛巴的頭。就是這樣(打響指),他明白了。但那是密法,我們不要談論它,因為現在密法太危險了(眾笑),所以我們不談這個。但即使在大乘,也有一個故事,關於佛陀拿起一朵蓮花,看着它微笑,像迦葉這樣的人就明白了。他明白了什麼?

He gets “no horn, no tail”, basically. That's what he got, “Oh, okay. No tail, no horn actually”. And he got this just because of the fact that Buddha picked up a lotus flower and smiled. There are many, many accounts like this. And a little bit less than that, there are also other methods. For example, I think this is very much in the Mahayana tradition, especially in the Zen tradition, they ask very ridiculous, strange questions, and through those questions the one who has the dilemma gets it.

他明白的是「無角無尾」,基本上,這就是他得到的。沒有尾巴沒有角,就像佛陀拈花微笑一樣,這樣的記載有很多很多。比這少一點的,還有其他的方法,比如說,在大乘的傳統,特別是在禪宗的傳統裏面,他們會問一些很荒唐的、很奇怪的問題,通過這些問題,有這種難題的人就明白了。

So here we are talking about a very particular way of getting that right view. Now I'm using the term “right view”, but bear in mind that the aim of Buddhism is to get away from the view. But for the time being, since we realize that having a wrong view is only going to lead us to pain, at least let's have the right view. So we are talking about the right view, and achieving that right view. If you are someone who has special faculties, you can even get it through the sight of a dead leaf falling.

所以我們在這裏說的是一種很特別的獲得正見的方法。現在我用的是「正見」這個詞,但是請記住,佛法的目的是為了「離見」。但就目前而言,既然我們意識到有一個錯誤的見地只會讓我們陷入痛苦,至少我們要有正確的見地。所以我們現在講的是正確的見地,以及成就這個正確的見地。如果你是一個有特殊福德的人,你甚至可以通過看見枯葉落下的景象,來獲得正確的見地。

Now I know it sounds really mystical, but it's actually not. It's really not. It's just causes and conditions. It can happen. Even in our mundane life, I think it happens. I'm not talking about some sort of spiritual experience, but just the shifting of your ideas. The shifting of your values. It happens. But anyway, that is special, but it's very individual. And it's very subjective. We don't know.

我知道這聽起來很神祕,但實際上不是,真的不是。這只是因緣而已,它是有可能發生的。即使在我們平凡的生活中,我認為它也會發生。我不是在說某種精神上的體驗,只是你的想法的轉變,你的價值觀的轉變,它會發生。但無論如何,那是特殊的,是非常個人化的,是非常主觀的。

But for people like us, using language is the only way

Okay, so practically, academically, intellectually, scientifically, as a human, what can we do to really actualize that truth? Buddhists have only found three ways. Hearing, contemplation and meditation. That's the only way for people like us. In other words, we need to use language. You know, hearing, language. We are not happy about it. It's not like hearing is so holy or something. It's out of no choice, reluctance. Reluctantly, in order to get rid of suffering, we need to use language because this is the only way.

那麼從實踐上、學術上、知識上、科學上,作為一個人,我們怎麼做才能真正證得這個實相呢?佛家只找到了三種方法:聞、思、修。對於我們這樣的人來說,這是唯一的方法。換句話說,我們需要使用語言。你知道,對於聽聞和語言,並不是我們想要這麼做,「聞」又不是什麼神聖的事情,而是出於無奈,是不情願的。為了擺脫痛苦,我們需要使用語言,因為這是唯一的方法。

Somebody needs to say, “It's okay, don’t worry, calm down”. It helps. And then once you calm down, this person says, “You know, can you feel it on your head? Why don't you put on your hat? See? It fits on your head. Don't you think that means that you have no horn?” You know, logic. Logic is always like this. It's very pathetic. It's actually really vague. And it’s very limited. But nevertheless it works.

需要有人說「沒事的,別擔心,冷靜下來」,這是有幫助的。然後一旦你冷靜下來,這個人就會說「你的頭頂有感覺嗎?你為什麼不戴上帽子呢?看到了嗎?它戴在你的頭上很合適。你不覺得這意味着你沒有角嗎?」這是邏輯,邏輯總是這樣的,很可憐。它實際上是非常模糊的,非常無力,而且非常有限,但它還是有效的。

So the only thing we can use is hearing, contemplation and meditation. I keep on using the word “meditation”, which I really don't like, but we will talk about that more tomorrow. So what's happening right now is that we are doing the hearing, meaning we are using logic. And yes, in the study of Buddhist philosophy, there is a big section where we study Buddhist logic. A lot.

所以我們能用的只有聞思修。在說修的時候,我一直在用 meditation(禪修)這個詞,我真的不喜歡這個詞,但是我們明天再談。所以現在的情況是,我們在做聽聞,也就是說我們在用邏輯。是的,在佛教哲學的研究中,有一大段內容是研究佛教的邏輯,很大的一段。

It’s not that logic is something that we really trust. Underneath, we always have a little bit of mistrust towards logic. In fact, there's a guy called Chandrakirti who actually has a very different attitude towards logic. He said, “Well, I don't have my own logic, but I'm going to use your logic to defeat you”. And this system became a really popular system of Buddhist philosophy in Tibet. It’s called Prasangika Madhyamaka. They call it consequentialism. It's really famous.

並不是說邏輯是我們真正信任的東西。在內心深處,我們對邏輯總是有一點點的不信任。其實,有一個叫月稱的人,他對邏輯的態度很不一樣。他說「好吧,我沒有自己的邏輯,但是我要用你的邏輯來打敗你」。而這個體系成為了西藏一個非常流行的佛教哲學體系,它被稱為「中觀應成派」,被稱為「應成」,它真的很有名。

I don't know. It’s something to think about, especially for those who have studied. It's something that you need to think about, especially for philosophy students or history students. I don't know so much about Western thought and history, but I have heard a little bit about rationalism. I have a feeling that after rationalism, the West should have invited Chandrakirti, because he was very critical towards rationalism. Logic. He sees faults in that. I think there's someone called Karl Popper who also talks about this. Anyway, let’s not get too intellectual here.

這是一個需要思考的問題,尤其是對於那些學過中觀應成派的人來說,尤其是對於哲學系學生,或者歷史系學生來說。我對西方思想和歷史的了解不多,但對理性主義還是有所耳聞的。我有一種感覺,理性主義之後,西方應該請月稱來,因為他對理性主義是非常批判的(譯:這裡說的理性主義,實際上就是批判主義,仁波切認為,月稱才是真正意義上的批判主義大師)。尤其是邏輯,他看到了其中的錯誤。好像有一個人叫 Karl Popper(卡爾波普),他也談到了這個問題。總之,我們不要在這裏搞得太智力化。(譯:卡爾波普就是前面講到的「可證偽性」的提出者)

The two truths: relative truth and ultimate truth

So when we are using the technique of hearing and contemplation, Buddhists have invented the idea of what we call relative truth and ultimate truth. Let's use the horn and tail analogy. In the horn and tail analogy, relative truth is basically what goes through the mind of the person who has taken the hallucinogenic substance. He can feel it. It's really bothering him. So it's true to him, and in fact if more than 51% of Australians take hallucinogenic mushrooms every day, your parliament will be different. Because relatively relative truth has got a lot to do with consensus and quantity, the percentage of the population that accepts something as true.

所以我們在運用聞思修的技術時,佛教徒發明了所謂的相對真理和究竟真理的概念。我們用角和尾巴來談這個,在角和尾巴的比喻中,相對真理基本上是指服用了致幻物質的人心中的想法。他能感覺到,這真的讓他很煩惱。所以對他來說是真實的,事實上如果有超過 51% 的澳洲人每天都在服用致幻蘑菇,你們的議會就肯定與現在不同了(眾笑)。因為相對真理跟共識有很大的關係,跟接受某件事情的人數和人口比例,有很大的關係。

But nevertheless, the Buddhist idea is that relative truth is okay, it's respected. This is what you think. This is what you see i.e. Buddhists do not deny your subjective experience. They accept that these experiences are “real” for you.. But the absolute truth is that on the absolute level, the horn and the tail do not exist i.e. the horn and the tail do not exist in objective reality outside your subjective experience. Just because you feel it doesn’t mean it’s real.

但盡管如此,佛教的觀念是,相對真理也是對的,是被尊重的,是你所想的,是你所看到的。但是,究竟真理的意思是:在究竟的層面上,角和尾巴是不存在的。(譯:仁波切時而使用 absolute truth 時而使用 ultimate truth,這只是語言上的技巧,以下都翻譯為「究竟真理」)

I need to define this more precisely. Actually the absolute truth is not that the horn and tail do not exist. On the most absolute level there’s neither existence nor nonexistence. There is not even talk about “It does exist before, and it does not exist later” i.e. it’s not that there’s a need to deconstruct of the horn and tail. Because the whole burden of the existence of the tail or its nonexistence is simply obsolete. The tail is fundamentally not there i.e. because there is no tail there on the absolute level, there’s nothing real that needs to be deconstructed. However, there is nevertheless a need to realize that the subjective experience of horn and tail in the relative truth does not correspond to the objective reality that there is no horn and tail, i.e. the absolute reality as it is.

我需要更准確地定義這個問題:究竟真理並不是說角和尾巴不存在。在最究竟的層面上,既不存在,也不不存在,也沒有一種說法是以前存在以後不存在。尾巴存在或不存在的整個思想負擔,就完全沒有了。從根本上說,這裡沒有尾巴什麼事。

Only someone who has taken the substance can talk about the subjective experience of horn and tail, “After you take the substance, you have the horn and the tail, and then when the impact of the substance is waning, then the horn and tail are slowly moving and fading away”. Only on that level can you talk about the existence of the tail or not.

只有服用過致幻物質的人,在服用致幻物質之後,才有了角和尾巴。然後當致幻物質的衝擊力減弱時,角和尾巴就會逐漸消失。只有在這個層面上,才能談得上尾巴的存在與否。

So that’s the absolute view and the relative view. I'm sorry to have to speak like this, because I wish I could sort of water this down this and simplify this. But there's also a danger of making it too simple. And if you do that, then the core essence and authenticity of Buddhism gets lost. We need to approach it this way.

所以這就是究竟的見地和相對的見地。我很抱歉要這樣講,我希望能淡化這個,簡化這個,但是,這樣也有一個危險,就是把它變得太簡單,那麼佛教的核心本質和真實性就會丟失。我們需要上面談的這個方法。

請大家記住,相對真理和究竟真理的區別,僅僅是為了溝通的需要,僅僅是為了創造和鋪設一條法道的需要。那我們為什麼需要法道呢?因為我們需要證得前面說的果。是什麼果呢?還記得嗎?不是獲得什麼東西,而是祛除什麼東西。你已經有頭了,你不需要再獲得頭,你需要祛除角,或意識到沒有角,或兩者都要。我們接下來會講。

So this is a paradox. This is how the whole world is. All phenomena. The paradox between the relative truth and the ultimate truth.

所以這是一個悖論。整個世界就是這樣。所有的現象,都是相對真理和究竟真理之間的悖論。

Relative teachings and absolute teachings

There is another thing. Maybe I'm confusing this too much. You know how we were talking about the Abrahamic approach? There is something to think about here. Not only in the Abrahamic approach, but in most of the modern approaches to studying anything such as science, technology, physics. These methodologies and approaches to studying the truth do not have obvious distinctions of relative truth and ultimate truth Ed.: DJKR is using “absolute truth” and “ultimate truth” interchangeably. Definitely most religions. This is just an assumption. I may be wrong, so please correct me. In my view, most religions seem to claim that whatever they're teaching is the ultimate truth. I will give you more examples. Whereas in Buddhism, not all the teachings are ultimate truth. In other words, there are lots of Buddhist teachings that are taught by the Buddha, and he never “meant it” i.e. not everything taught by the Buddha is meant as a statement of absolute truth.

還有一件事。也許我把這個搞得太復雜了。還記得我們剛才說的亞伯拉罕宗教的方法嗎?這裏面有一些值得思考的地方。不僅在亞伯拉罕宗教中,而且大多數現代研究方法,例如科學、技術、物理學,這些研究真理的方法和途徑,並沒有顯著地區分相對真理和究竟真理。大多數宗教肯定是。但這只是一種假設,我可能是錯的,所以請糾正我。在我看來,大多數宗教似乎都聲稱他們所教的東西是究竟真理,這個我再舉例說明。而在佛教中,並不是所有的教義都是究竟真理。換句話說,佛教中有很多很多教授雖然是佛陀教的,但佛陀並不是那個意思。

It's all in the category of, “It's okay. Don't worry”. “It's okay. Just drink some water”, as if the water is going to shrink the horn, the non-existing horn. There is a lot of that in Buddhism. And under this section falls all the teachings about things like meditation, karma, and reincarnation. All these teachings fall under that category of teachings that are not meant as a statement of absolute truth.

而是屬於「沒事的」「喝點水就好了」這一類,好像水會讓那個不存在的角縮小一樣。佛教裏有很多這樣的內容,例如所有關於禪定的教法,關於業力的教法,關於輪迴的教法,都屬於那一類的教法,並不是要作為對究竟真理的闡述。

There are teachings that are taught by the Buddha where he really “meant it” to be taken literally. There are many sutras such as the Heart Sutra, Prajñaparamita Sutra, Vimalakirti Sutra, Vajracchedika Sutra. There are quite a lot. But even amidst these absolute sutras, there are so many relative teachings.

有的教法是佛陀講的,他就是那個意思,你可以按字面意思理解的。如《心經》、《般若波羅蜜多經》、《維摩詰經》、《金剛經》等等,有相當多。但即使在這些究竟的經論中,也有那麼多相對的教法。

The relative truth and ultimate truth are always in union

I'm going to illustrate this a little bit. It's like this. Suppose you go to a place where the most pure or fundamental Buddhist teachings are taught, such as Thailand or Sri Lanka, because that's where Theravada Buddhism is taught. Theravada Buddhism is the oldest, most fundamental. It’s actually the root of Buddhism. It’s really important. If you go there, you can observe something very paradoxical, very contradictory.

我要說明一下這個問題。它是這樣的,假設你去一個傳授最純正或最根本的佛教教義的地方,比如泰國或斯裏蘭卡,因為那是傳授上座部佛教的地方。上座部佛教是最古老、最根本的,實際上是佛教的根基,真的很重要。如果你去那裏,你可以觀察到一些非常矛盾的東西,非常矛盾。

The monks will teach you teachings such as Abhidharma, which includes teachings such as anatta where we hear that there is no self. But then these Theravadins are also the ones who are crazy about conduct, ethics, discipline, robes, merit, begging alms. You're supposed to offer alms, to bow down. “You can't do this. You can't do that”. There is so much of that. Can you see the contradiction? Even in the most pure fundamental Buddhist traditions you find this. Why? Why is it like that? Because in the Buddhist view, the relative truth and ultimate truth are actually in union. This is always the challenge.

那裡的僧人會教你阿毗達摩等教法,包括 anatta(無我)的教法,在這裡你會聽到「無我」。但是,這些上座部的法師們也是對行為、倫理、紀律、袈裟、功德、托缽乞食非常瘋狂的人。「你應該要施捨,要低頭行禮。」「你不能做這個,不能做那個。」有這麼多的內容。你能看到這個矛盾嗎?即使是在最純正的佛教傳統中,你也會發現這一點。為什麼會這樣?因為在佛教看來,相對真理和究竟真理其實是結合在一起的。這始終是個挑戰。

Now, if you shift to places like Tibet or Bhutan, it's really so confusing. You meet monks who have shaved their head, as if there’s something wrong with hair. They zealously and diligently shave their hair as part of their discipline. But right there you also meet yogis who only worry about dropping i.e. losing their hair. They keep their hair. Every lock of hair, they say, is like dakinis, like mandalas. So they keep their hair. Some of them they keep their hair throughout their whole lives. I don't know whether you have seen any of them, with really smelly and really long, big dreadlocks.

現在,如果你去到西藏或不丹這樣的地方,真的是太讓人混亂了。你會遇到那些剃頭的僧侶,好像頭髮對他們有害似的。他們熱衷而勤奮地剃除頭髮,作為他們戒律的一部分。但就在那裏,你也會遇到只擔心掉頭髮的瑜伽士,他們保留自己的頭發。他們說,每一縷頭髮都是空行母,或壇城,等等等等。所以他們蓄髮,有些人一輩子都在蓄髮。我不知道你們是否見過,有著又臭又長的大辮子。

There are many varied expressions of nonduality in Buddhist culture, lifestyle and symbolism

The fact that there can be such divergent and seemingly contradictory approaches to the path and practice of Buddhism is perfectly fine for Buddhism. It's really a nondual view. That's why it permeates all this culture, all this sort of Buddhist lifestyle, if you like. The lifestyle. The symbolism. Even the symbolism.

這對佛教來說,完全沒問題!這其實是一種非二元的觀點。這就是為什麼它滲透到所有的這種文化,所有的這種佛教的生活方式。它是一種生活方式,甚至是一種象徵主義。

As I've said many times before, if you go to a Buddhist temple, there is iconography there. Monks. The image of serene, simple, renunciant monks or nuns is very much venerated. The idea that a savior or a master, especially a spiritual master, has to be serene, simple, renunciant, ascetic, with begging bowl and bare feet. There's a lot of that in the Buddhist temples, especially in Tibet. On another side, there are not-so-serene figures. Wrathful deities. Not so simple. Bodhisattvas with earrings, nose rings, anklets, adorned with all sorts of garments. And then, if it is a tantric temple, there are some amazing figures which are also equally venerated and appreciated. And there are many followers of each of these different approaches to Buddhist culture, lifestyle and symbolism.

我以前說過很多次,如果你去佛寺,僧人幾乎是一種符號。寧靜、簡單、出離的比丘或比丘尼的形象,是非常受人尊敬的。人們認為,救世主,上師,尤其是精神上的上師,必須是寧靜,朴素,出離,苦行,有乞食的鉢,和赤脚而行的。在佛教寺廟裏,尤其是西藏的寺廟裏,有很多這樣的東西。另一面,也有不那麼寧靜的圖像,像是憤怒的神靈。不那麼簡單的菩薩,帶着耳環,鼻環,脚鍊,各種莊嚴的飾品。然後,如果是密宗的寺廟,還有一些神奇的圖像,也同樣受到人們的尊敬和讚賞,也有很多追隨者。

Can you imagine now? I don't know if you can imagine. Let’s suppose you are a follower of Buddhism and you are looking at three different examples. There's the St. Francis of Assisi-like Shariputra. And then there is a limousine-driving multimillionaire with gold rings and gold plated teeth, someone like Avalokiteshvara. And then there is a prostitute, a half-time prostitute half-time arrow maker like Saraha’s guru Ed.: she is known as the Arrow-Making Dakini. So you have these three. Now as a follower of Buddhism, can you see the seeming contradiction? But all this fits in the mind of people who can appreciate the culture of nonduality.

你能想象的了嗎?假設你是一個佛教的追隨者,你正在看三個不同的榜樣。有一個聖方濟各亞西西(13世紀天主教著名的苦行僧)那種類型的人:舍利弗。然後是一個開着豪華轎車,戴着金戒指,鑲着金牙齒,億萬富翁那樣的人:觀世音菩薩。還有一個是兼職妓女,且兼職造箭師的人:薩拉哈的上師。所以你有這三種榜樣。現在作為一個佛教追隨者,你能看出這看似矛盾的地方嗎?但這一切都能進入一個人的心,只要他能體會到非二元的文化。

It's there but it's not there (it's there and it's not there)

Why is all this diversity and seeming contradiction accepted? Because of the view of Buddhism. Let’s go back to the horn and the tail. Is the horn there? Yes, it's there, but it's also not there, at the same time. Is the tail there? Yes, it's there, but it's also not there, at the same time. This is called the union of appearance and emptiness. This is one of the most important ways to understand the Buddhist view.

為什麼?因為佛教的見地。我們再來看看角和尾巴,角在不在?是的,它是在那兒,但它又是不存在,同時發生。尾巴在不在?是的,它是在那兒的,但它又是不在的,同時發生。這就是所謂的,顯現與空性的雙運,這是理解佛法見地的一個最重要的方法。

Basically, everything is there, but it's not there i.e. we experience phenomena as subjectively real in the relative truth, even though they are not objectively real in the ultimate truth. Just like the experience of the horn and tail, which feels very real as a subjective experience, even though they are not there in reality. This is really difficult to understand. Not intellectually, but habitually.

基本上,一切事物都是在那兒的,但又是不存在的,這真的很難理解。不是智力上,而是習慣上很難接受。

You are looking at me right now. And actually, I'm here but also not here. How can you make sense of this? It's difficult. “He's there. He's sitting there. He’s talking nonstop. When is he going to stop talking?” Why do you experience me in this way? Because you have drunk something. You have been eating something endlessly. That's why. Even worse than your horn and tail, I'm here. In your mind. This.

你現在正看着我。而實際上,我在這裏,但也不存在。這怎麼能理解呢,很難很難。「他就在那裏,他就坐在那裏,他在不停地說話,他什麼時候才會停?」為什麼你會以這種方式感受到我?因為你喝了些什麼,因為你一直在無休止地吃某種東西,這就是原因。我在這裏,在你的腦海裏,這比你的角和尾巴更糟糕。

But by the way, this experience is not too foreign though. It's not too foreign. This kind of experience does exist, just like the hallucinogenic experience. It’s like when you are watching a movie. Whatever is happening in the movie, it's there. And therefore it really makes you cry. It makes you angry. It makes you feel nervous. It makes you feel suspenseful. And so forth.

不過,順便說一句,這種體驗並不太陌生。我是說,這種致幻體驗,有點像你在看電影。不管電影裏發生了什麼,它都在那裡。因此它真的會讓你哭,讓你生氣,讓你感到緊張,讓你覺得懸念重重,諸如此類。

But you also know it’s not there. And what does this awareness do? It releases you from a lot of unnecessary problems. For instance, while you're watching a movie, if you need to go to the toilet, you go, don't you? You don't hold it back and think “No I can’t go yet, first I have to sort this out". Because you know that it's there but it's not there. Especially you can pause it these days, and you can even rewind it and play it back. Because you know that it's there but it's not there.

但你也知道它是不存在的。這種覺知有什麼用呢?它把你從很多不必要的問題中解放出來。例如,當你在看電影的時候,如果你需要上廁所,你就會去,是不是?你不會憋著,並且想著「不,我還不能去,首先我得把這個問題解決了」。因為你知道它在那裏,但它又不存在。尤其是你現在可以暫停,甚至可以倒帶,回放。因為你知道它在那裏,又不存在。

That’s why you are awakened. Buddha. Enlightened from this delusion of thinking that it’s there or not there.

這就是你為什麼能覺醒,成佛。從認為有,或認為無的妄想中證悟。

The Buddhist view is taught using different words, but all of them are inadequate

I really needed to express this first, because this is sort of the more classic way to understand the Buddhist view. I'm going to break it down a little bit, as I'm sure there are a lot of people here who are completely new to the Buddhist path. So, for their sake, those who have received many Buddhist teachings, you have to bear with me a little bit.

我真的需要先談一談這個,因為這算是比較經典的理解佛法見地的方式。我要把它分解一下,因為我相信在座的有很多人是完全沒有接觸過佛法的。所以,為了他們,你們這些接受過很多佛法教授的人要忍耐一下。

This is really important to know. The Buddhist view. The fact that it’s there but it's not there. This view is taught using many different yet inadequate expressions in words and language, but we have no choice but to use language.

這一點真的很重要。佛法的見地就是:它在那兒,但它又不存在。這種見地是用很多不同又不充分的語言文字和表達方式來教導的,但我們別無選擇。

One such form of language is “Everything is illusion". You have heard this many times. This is one of the Buddhist views. Many people present it that way, “In Buddhism, life is an illusion”. It's fine this way. But you have to be careful, because I think that the way we are conditioned means that when we hear the word “illusion”, we immediately come to the conclusion that “It does not exist”. But that's not what Buddhists are saying. Always go back to “It's there but it's not there”.

有一種這樣的語言形式是「一切都是幻覺」。你已經聽過很多次了,這是佛教的見地之一。很多人這樣介紹:「佛教中說,生命是幻覺」。這種方式很好,但是你要小心。因為我覺得,我們受制於這樣的因緣:當我們聽到「幻覺」這個詞的時候,我們馬上就會得出「它不存在」的片面結論。但佛教不是這麼說的,佛教總是回到「它是在那兒的,但它又不存在」。

Another approach is that we hear the Buddhist view expressed using terms such as shunyata or emptiness, “Everything is emptiness”. And again, this has led a lot of people to a lot of misunderstanding. Especially if you read classic sutras with words such as “No nose, no eyes, no ears", it really sounds like a negation. But as I said when I gave you the example of somebody falling from the cliff but managing to grab a branch with their teeth, it’s like this. All words are not good.

另一種做法是,我們聽到佛教的觀點是用 shunyata(空性)這樣的術語來表達的,比如說「諸法皆空」。而這又讓很多人產生了很多誤解,尤其是當你讀到經典的佛經時,用「無眼耳鼻舌身意」這樣的字眼,聽起來真的是一種否定。就像我舉例子的時候說過,有人從懸崖上掉下來,只能用牙齒咬住一根樹枝。就像這樣,所有的語言都是不對的。

But when I say this, again you may immediately think that the truth must be something mythical or mystical, something very exotic. No, we're not talking about that at all. We are talking about something raw. This moment. What's happening.

但是,當我說這句話的時候,你又可能會馬上這樣想:真相一定是一些神話或神祕的東西,是一些很奇特的東西。不,我們說的根本不是這個,我們說的是一些原始的東西。這一刻,正在發生的事情。

It's fairly easy to understand this intellectually, but really difficult to understand habitually. Very difficult. There are many reasons. There is lots and lots of denial. And there are lots and lots of causes and conditions to make you forget that it's there but it‘s not there. In fact, all our endeavors, everything we buy, everything we possess, and everything we do is somehow related to forgetting this fact that it’s there but at the same time it’s not there.

這在智力上相當容易理解,但在習氣上真的很難理解,非常難。有很多原因,有很多很多的否定,還有很多很多的因和緣,讓你忘記「它在那兒,但它又不存在」。事實上,我們所有的努力,我們所買的一切,我們所擁有的一切,我們所做的一切,都與忘記這個事實有關:它是在那兒的,但它同時又不存在。

We usually focus on just one of the two aspects, either "it's there" or "it's not there"

It's really difficult to talk about. It's there and it's not there. We speak about this in terms of two truths and using two phrases, “it’s there” and “it’s not there”. Even though they are one. It’s the same thing. It's like the reflection of the moon in the water. It’s there and it’s not there at the same time, and it's exactly one thing.

當我們面對某件事情的時候,談論「在那兒又不存在」是很難的,這取決於你的第一念。這真的很難講清楚,「在那兒又不存在」看起來像兩個東西,但其實他們是同一個東西,就像月亮在水中的倒影。它在那兒和它不存在是同時的,這完全是一件事。

But we're talking about the view. And when we talk about a view, we're talking about the viewer, the subject. So depending on the subject, when the subject faces something or experiences something, he or she make not see both aspects of “it’s there” and “it’s not there” together. Let’s suppose we face a situation or we look at something or we encounter something. What is your first experience? If you are really good at it, you can swallow these two aspects together, because you know that it's one.

我們說的是見地,而當我們談論見地的時候,我們談論的是持有見地的人,是主體。所以根據主體的不同,當主體面對某件事情或經歷某件事情時,會先朝着「它不存在」的部分跌跌撞撞地往前走。當然,如果你真的很優秀,你可以把這兩個方面一起吞下去,因為你知道這是一個。

But if you are not really good at it, then sometimes you end up stumbling towards the “It’s not there” part first. The first thing you hear or experience when you encounter a life situation is the “It’s not there” aspect. What does it do? It makes you nihilist, hopeless, depressed. It’s not there. You become critical. You begin to read things like Nietzsche. You will smoke cigars and drink thick coffee. Broadly speaking, if you were to make a sweeping statement, all that comes out of that “It’s not there”. Everything is deductive and reductionistic.

但如果你不是很擅長,那麼當你遇到生活中的情況時,你首先聽到或體驗到的就是「它不存在」這一方面。這會怎樣?這會讓你變成虛無主義,無望,沮喪。你變得具有批判性,你開始讀尼采,你會抽雪茄,喝濃咖啡。這一大群的東西就出來了,還記得一棍子打死很多人嗎?(眾笑)怎麼說呢,一切都是演繹推理。

And it's very strange actually. Many times we also feel very proud of being nihilist, proud of having that kind of negative, nihilistic depression. It's a style. These kind of people have a different and unique smell also. They have their lifestyle. They hang different things on their walls. They wear different kinds of perfume. I'm serious. Their shoes. They wear different shoes. They hang out with that same kind of people. They love each other, but they also hate each other, because the other one is more nihilist than you.

而這其實是非常奇怪的。很多時候我們會為自己是虛無主義者而感到非常自豪,為自己有那種消極的虛無主義的抑鬱而感到自豪。這是一種風格。這種人也有一種不同的獨特的氣味,他們有他們的生活方式,他們在牆上掛着不同的東西,他們噴不同種類的香水,我是認真的,他們穿不同的鞋子,他們和同一類人一起出去玩。他們彼此相愛,但他們也恨對方,因為對方比他更虛無主義。

Sometimes in our life, or some people, when they face a life situation, the first thing they encounter is the “It’s there” part. They fall into being eternalists. Then they become righteous. Maybe they become fascist. They end up becoming believers in things like free speech. They end up becoming believers in things like democracy. They have their style.

在我們的生活中的另外一些時光,或者說另外一些人,在面對人生境遇的時候,他們首先遇到的是「它在那兒」的部分。他們就會陷入成為存永恆主義。然後他們就變成了正義主義者,也許,他們會成為法西斯主義者,他們最終成為言論自由等事物的信仰者,他們最終成為民主等事物的信仰者。他們又有他們的風格。

You should observe this. If you're good at it, you can almost tell “Yes, that's a nihilist person” or “That's an eternalist person”. It’s a bit like liberal and conservative. You can almost tell who is who. But sometimes things get confusing, because maybe in the morning you are nihilist but in the evening you become eternalist. It really permeates every aspect of our life.

你應該觀察這一點。如果你善於觀察,你幾乎可以分辨出「那是一個虛無主義者」或「那是一個永恆主義者」。這有點像自由派和保守派,你幾乎可以分辨出誰是誰。但有時事情會變得混亂,因為也許在早上你是虛無主義者,但到了晚上你就變成了永恆主義者。這些真的滲透到我們生活的每一個方面。

Okay, we'll take a break, and then we’ll come back with some questions and answers.

好了,我們休息一下,然後我們再回來,回答一些問題。

譯者按

仁波切在最近幾年的課程中,不斷提到「It’s there but it’s not there」這句核心觀點。but 在這裡也有 and 的意思。剛開始,我只是按字面簡單地翻譯成「它在那又不在那」,或有時翻譯成「它存在,但又不存在」。但我一直覺得,這種表述不夠好,並沒有對理解這句話有什麼幫助。

這讓我一直有點點負罪感。這句話承載了仁波切對整個佛法見地體系的總結,卻被我翻譯成了「存在又不存在」這種鬼話,只會徒增讀者的困惑。因此,在我糾結了很長一段時間之後,在本文中,我把「It’s there but it’s not there」翻譯為「它在那兒,但又不存在」。

雖然,這種翻法破壞了原文的對稱性,以及強烈的視聽衝擊,缺乏美感,但確實是忠實於仁波切本人的意思。是目前譯者可選擇的最好版本。

所謂正確的見地,其實是依錯誤的見地而說。錯誤的見地有兩種,一是認為某人某事是真實存在的,由此而產生愛恨情愁;二是簡單地認為某人某事不存在,是幻象,因而失去興趣,退縮逃避。對於前者,佛法的教育是 It’s not there(它不存在),而對於後者,佛法的教育則是 It’s there(它就在那兒)。

後一種教育法,也被稱為「它有作用」或「它有現象」。合在一起,就是「只有現象沒有本質」,或「無自性而有作用」,甚至「明空雙運」等說法。所以我才覺得「它在那兒,但又不存在」能更好地理解「It’s there but it’s not there」。

此外,如果您想要翻得文藝一點,好作為社交網絡的簽名檔,那麼我推薦「似有或無」。

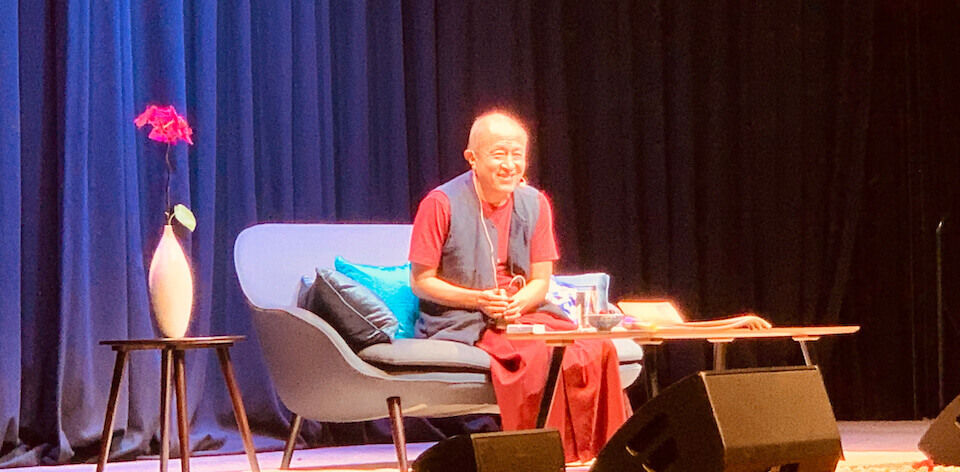

宗薩欽哲仁波切,於 2020年1月25-27日(農曆新年)在澳大利亞悉尼的新南威爾士大學,給予了為期三天的教授,題目為《見修行》。英文部分由 Alex Li Trisoglio(仁波切指定的佛法老師)聽寫,並分段和添加標題,發布在 Madhyamaka.com。中文部分由 孫方 翻譯。並在翻譯過程中,根據視頻做了文字上的修訂,所以中英文部分可能會有可忽略不計的微小差別。照片為課程現場。