譯者按:頂禮本師釋迦牟尼佛!恕譯者才疏學淺,未明心要,謬誤在所難免,僅供參考。所譯文字未經上師認可,或專業翻譯機構校對,純以個人學習為目的,轉載或引用請慎重。

The middle way is difficult to understand and accept

Language such as “existence” and “nonexistence” is very deceiving and really difficult. These words are very vague. How do you define “existence”? You need to think about that. Because in the human mind, when we define whether something exists or does not exist, it’s very connected to things like time, space, usage or function, and as I said earlier, consensus17. But none of them really solidify and make something exist truly or more truly, or make something not exist.

像「存在」和「不存在」這樣的語言是非常具有欺騙性的,很難理解的,非常模糊的。你如何定義存在?你需要思考這個問題。因爲在人的頭腦中,當我們定義一個東西是存在還是不存在的時候,它跟時間、空間、用途或功能等東西有很大的聯繫,就像我剛才說的:共識。但它們都不能真正固化並使某物真實存在,或者更真實地存在,或者使某物不存在。

When you try to comprehend the Buddhist view, you also have to get used to the distinctions of nonexistence and existence, and the dangers and implications of falling into either one of them. The Indian wisdom traditions in general are really concerned not to fall into eternalism or nihilism. They always value the middle way. I don’t know whether that is the case with other systems. I have very little knowledge about Abrahamic systems, but sometimes I feel they don’t even see it as “falling into” an extreme i.e. they don’t see it as a downfall. They don’t even call it an “extreme”. Instead, they teach that’s the way to go. From the Buddhist point of view, they’re almost proud of falling into one extreme and believing that something truly exists or does not exist. They’re proud of seeing some things as permanently and ultimately good and some things as permanently bad.

當你試圖理解佛教的見地時,你也必須習慣於不存在和存在的分別,以及落入其中任何一種的危險和影響。一般的印度智慧傳統,真的很在意,不要落入永恆主義或虛無主義,他們總是重視中道。我不知道其他系統是否也是如此,我對亞伯拉罕宗教體系的瞭解非常非常少,但有時我覺得他們不認爲這是一種墮落,他們甚至不稱其爲極端。相反,他們教導說,這是一種方式。從佛教的角度來看,他們幾乎以落入一個極端爲榮,認爲有些東西真正存在或不存在。他們以「把一些事情看成是永恆的究竟的善,把一些事情看成是永恆的究竟的惡」爲榮。

The Indian wisdom traditions generally, and especially Buddhism, are very wary of this. They are wary of believing in things as truly good, truly bad, truly existing, truly not existing. But as I said, it is difficult, especially habitually speaking, for you to really see me as “there, but not there”. Of course, I’m not asking or demanding that you see me as nonexistent. That’s crazy. That’s not only crazy, but it’s defeating i.e. going against the Buddhist view. Instead, what I’m demanding, so to speak, is that when you are reading the Heart Sutra and when you look at me, just know that I am there, but I’m also not there.

一般來說,印度的智慧傳統,尤其是佛教,對此非常警惕。他們對相信事物是真善、真惡、真實存在、真實不存在都很警惕。但是我說過,你要真正把我看成「在又不存在」,是很難的,尤其是習慣性的。當然,我並不是要求或苛求你把我看成不存在的,那是瘋狂的。那不僅是瘋狂的,而且是失敗的,即違背了佛教的觀點。相反,我所要求的是:可以這麼說,如果你讀過《心經》,當你再看我的時候,就知道我是在那兒的,但我也是不存在的。

It’s just like the blonde girl in the Game of Thrones Daenerys. She is there but she’s not there. And her dragon is there, but it’s not there. When you know this, then you can go on and on talking about “Oh, come on, she should have become a queen. She should not have become a queen. Is she still alive because her body got carried away by her dragon?” All that, you are free to think whatever you want to think. But it’s all within the sphere of “It’s there, but at the same time not there”.

就像《權力的遊戲》中的金髮女孩丹妮莉絲。她在那裏,但她不存在。她的龍也在那裏,但它也不存在。當你知道這一點,那麼你就可以繼續和談論「哦,她應該成爲女王。她不應該成爲女王。她的身體被她的龍帶走了,所以她還活着嗎?」所有這些,你想怎麼想,就怎麼想。但這都是在「它在那裏,但同時又不存在」的範圍內。

This is sort of the most simple way I can present the Buddhist view.

這算是我對佛教的見地,能給出的最簡單的介紹。

And as simple as it sounds. It’s not only difficult habitually, and again I’m repeating, but also it’s really really important, more than ever. More than ever, this nondual way, this middle way of understanding the truth is really important. Because we just fall so easily and too much to the right or to the left. We have two problems. We overly believe in things that are believable. Overly, too much. Or we overly do not believe in things that are not believable. And that leads us to unnecessary hope and fear, assumptions, tensions and anxiety and all that. Okay, maybe some questions. We have half an hour.

聽起來很簡單,但在習氣上接受起來很難。我又在重複,而且它真的非常重要,比任何東西都重要,比以往任何時候都重要。這就是非二元,這就是真理,我們稱之為中道。因爲我們就是太容易太容易掉到右邊或者左邊,我們有兩個問題:我們總是過分相信那些容易相信的東西。重點是過分的,太相信了。以及,我們過分地不相信那些不容易相信的東西。從而這導致我們無用的希望,恐懼,假設,緊張,焦慮,和所有這些。

Longing for things that cannot be longed for

Q: Rinpoche, I believe I am eternalist in the morning and sinking into nihilism by the evening. In most cases. Sometimes the horns are an adornment, sometimes they’re very painful and I feel stuck in the middle. And I’m at a loss to know, in our language, where do we fit?

問:仁波切,我相信我早上是永恆主義者,到了晚上就會陷入虛無主義,在大多數情況下。有時角(譯:仁波切的比喻,見 Part 2)是一種裝飾,有時是非常痛苦的,我覺得卡在中間。而我也不知道,用我們的語言來說,我們該怎麼辦?

DJKR: The second part? Can you tell me again?

仁波切:第二句話?你能再說一次嗎?

Q: The horns are sometimes playful, an adornment, beautiful. But they can also be very painful.

問:角有時是好玩的,是一種裝飾,很美。但也會讓人很痛苦。

DJKR Right.

仁波切:對的。

Q: So being aware of that a little is painful, the actual dichotomy.

問:所以意識到這一點是很痛苦的,實際二分法。

DJKR: Being aware of that fact, and then still being dragged to the old habit?

仁波切:意識到這個事實,然後還是被拖到了老習慣上?

Q: Yes.

問:是的。

DJKR: The Buddhists would say, “Hmm, you are becoming a Buddhist”. Yes, that’s what they will say.

仁波切:佛教徒會說:「哈,你越來越像一個佛教徒了」。是的,他們會這麼說。

Q: But in language, there’s no word for nondualism. It’s not a word.

問:但在語言中,沒有一個詞來表達「非二元主義」。它不是一個詞。

DJKR: Yeah, true. It is. I know isn’t that strange? Yes. So?

仁波切:是的,沒錯,我知道(仁波切無奈的樣子)。是不是很奇怪?是的。所以呢?

Q: So I cry. I’m standing here and I’m crying.

問:所以我哭了。我站在這裏,我哭了。

DJKR: Yes, I think it’s called sort of training to long for the un-longable i.e. that which cannot be longed for, which is good. Because if you don’t do that, the chances are very high that you will long for things that will take you to trouble. So you might as well cry and long for that which is not longable, because in the long run, it will give you more freedom.

仁波切:是的,這個叫做「渴望那些無法被渴望的東西」,這是好的。因爲如果你不這樣做的話,你渴望的其它東西,給你帶來麻煩的機率會非常大。所以,你不妨繼續哭,同時渴望那些無法被渴望的東西,因爲從長遠來看,它會給你更多的自由。(鼓聲)

There is no truly existing karma or reincarnation

Q: Rinpoche, you said earlier that karma is falsifiable. Can you explain how that is?

問:仁波切,您剛才說因果報應是可以證僞的。您能解釋一下這是怎麼一回事嗎?

DJKR: Karma is within the sphere of this “It’s there, but it’s not there”. And also karma is a relative teaching. I was giving the example of how even the Theravada countries talk about anatta, selflessness, and at the same time they talk about shaving your hair if you are a monk. You could almost argue with them, “Who is shaving? What do you mean by hair?” There is no head. There is no hair. Yet karma falls into this union. Yes, on the level of the relative world, in the world of horn and tail, karma functions because you have taken that pill. Once that is gone i.e. once the effect of the pill has worn off, there is no karma.

仁波切:業力是在這個「在又不存在」的範圍內。而且業力也是一個世俗諦的教法。我剛才舉例說,即使是上座部國家也在講「無我」,而同時,他們也在講,如果你是出家人,就要剃髮。這時你可以跟他們爭論:誰在剃髮?什麼叫頭髮?沒有頭,沒有頭髮。業力就屬於這兩種教法的合一。是的,在世俗世界的層面上,在角和尾巴的世界裏,業力是有作用的,那是因爲你吃了藥。一旦藥效消失,就沒有了業力。

Q: So it’s falsifiable once you’ve taken a pill, is that what you’re saying?

問:所以一旦吃了藥就可以證僞了,你是這個意思嗎?

DJKR: Because actually there is no karma, and there is no agent of karma. It’s like this. Not only karma, but also reincarnation is falsifiable. It’s a bit like “Four legs, plank, my cup is here and my book is here. It’s a table”. That’s karma, isn’t it? Things put together, tougher with habit and culture and also circumstances. If the organizers here, Siddhartha’s Intent, if they only put this table here in the middle of this stage and if I were sitting on it, many of you might think “These guys have really put a very strange throne for Rinpoche today”. You see DJKR snaps his fingers the table does not exist at that time. DJKR snaps his fingers The throne suddenly came. That’s how karma works. And reincarnation also works just on that level. But when I use the word “just”, I’m not using it in a sort of demeaning way. I’m not devaluing it at all. It’s so powerful, just like the horn and the tail. So powerful.

仁波切:因爲其實沒有業力,也沒有業力的受者。不僅業力,轉世也是可以證僞的。這有點像,這裡有四條腿,有一塊木板,我的杯子在這裏,我的書在這裏,因此這是一張桌子,這就是業力。就是把事情放在一起,再加上習慣和文化,再加上環境。如果這裏的主辦方(悉達多本願會),只是把這個桌子放在這個舞臺中間,如果我坐在上面,很多人可能會覺得,這些人今天給仁波切安排了一個很奇怪的寶座。你看(仁波切打了個響指),那個時候桌子是不存在的,寶座就突然出現了。這就是業力,而轉世也只是在這個層面上運作。但當我使用「只是」這個詞時,我並不是以一種貶低的方式使用它,我一點也沒有貶低它的價值。它是那麼強大,就像角和尾巴一樣,那麼強大。

The compassion of the Buddha and why prayer works

Q: Since you are speaking about the whole sense of viewing things as being both real and not real, how would Buddha relate to the fires and the problems that are happening in Australia now? How would their compassion look?

問:既然您講的是觀照事物的整體意義,既是真實的,也是不真實的,那麼佛陀會如何看待澳洲現在發生的火災和問題?他們的慈悲心會是怎樣的?

DJKR: Yes, as soon as we talk about the Buddha and the compassion of the Buddha we need to talk about the perspective of the observer. Right at the beginning I was talking about empiricism. Empirical. As soon as you talk about the Buddha and the compassion of the Buddha, then we’re talking about someone else’s projection of the Buddha. So yes, that’s why I strongly believe that the Buddha has the compassion, the power, the omniscience to see this i.e. the problems currently happening in Australia. So now what we need to do is to create the causes and condition to invoke his compassion and power, and do the prayers, which I’m going to do towards the end of this session. And those who have the cause and condition of blind belief that I have, please join. You know, I have fallen into the eternalism of believing that there is a Buddha, there is his compassion, there is his omniscience and power, and therefore I will do prayers. Because I’m not awakened yet, so I’m still stuck with this projection. There will be people who say, “Ah, that’s just a story. There is no Buddha. There is no compassion. The fire will be extinguished by the fire people or whatever. Or not”. That’s how phenomena function. So prayer works, basically. That’s what I’m saying. Prayer works. This is what Nagarjuna would say: If not for this {i.e. “it’s there, but it’s not there” then prayer will never work. Then things would be unchangeable and predestined. Remember, right at the beginning, I was talking about free will? If not for this, then things would be predestined, and you would just have to wait until that fate is finished. But no. Because it is an illusion, that’s why something is doable. That’s why prayer works. Firemen works. If politicians act, if they have their act together, it could work.

仁波切:是的,還記得剛開始我們談到的經驗主義嗎?你一談佛陀和佛陀的慈悲,那我們就在談別人對佛陀的投射。所以,是的,這就是爲什麼我堅信佛陀有慈悲心,有力量,是全知的(能看到澳洲目前發生的問題)。所以,現在我們要做的是創造因和緣來喚起他的慈悲和力量,並做祈禱,我將在這節課的結尾做,跟我一樣盲目信仰因緣的人,請加入(眾笑)。你知道,我已經落入了永恆主義,相信有佛,有他的慈悲,有他的全知和力量,所以我要做祈禱。因爲我還沒有覺醒,所以我還停留在這個投射上。會有人說:那只是一個故事,根本就沒有佛,沒有慈悲心,火什麼的都是被消防員撲滅的。我要說的就是,祈禱是有用的,現象界就是這樣運作的。龍樹會這麼說,如果沒有前面說的這一切(在又不存在), 那麼祈禱永遠不會起作用,事情將是不可改變的,是註定的。記得一開始,我就說到什麼是自由意志嗎?如果不是這樣,那麼事情就會是註定的,你只能等命運自己結束。因爲它是一種幻覺,所以有些事情才是可以做的,所以祈禱才有用,消防員才有用,如果政客們能團結起來,他們就能成功。

The snake and the rope and the horn and the tail

Q: Rinpoche, you used to talk about the snake and the rope. The snake and the rope, are they like the horn and the tail?

問:仁波切,你以前經常說到蛇和繩子。蛇和繩子,它們是不是像角和尾巴一樣?

DJKR: Yes, I was using an updated example.

仁波切:是的,我用的例子升級了。(眾笑)

Letting go of self and seeing the truth

Q: Hello. I wanted to ask what you recommend when it comes to letting go of self, especially because amongst our generation of younger people, we’re bred into the idea of having to find our self. And now it’s this whole idea of letting go of that. It’s pretty hard to come to terms with, but I wonder how you would start to go about that?

問:你好。我想問一下,當談到放下自我的時候,你有什麼建議,尤其是在我們這一代年輕人當中,我們被灌輸了要「追尋自我」的想法。而現在我聽到的是關於「放下」的想法,這是很難接受的,但我想知道如何開始去做?

DJKR: It is really good that you ask this. Because this is exactly why I think the Buddhist view and also the meditation and action really can contribute, especially to the modern world. I don’t know, but the idea of “letting go” seems to have a lot of connotations of “sacrifice”. It’s painful. I for one don’t want to sacrifice things. I think it’s much more profitable and much more soothing to really get used to the idea that this self is there, but it’s also not there. So there’s nothing to let go of, but also that is a letting go. I think that’s more profitable. We will talk about this more. For example, especially young people, they are so much into being cool. Cool, fashionable, unique. I think the idea of “I’m there but I’m not there” could really help to enhance confidence. I need to really contemplate on this phrase “letting go of self”. It sounds to me like a sacrifice. Sacrifice. Yes, some people may be able to do it. But why not see the truth? That’s actually a much better sacrifice I think.

仁波切:你的問題真的很好。因爲這正是爲什麼我認爲佛教的見地、禪修和行動真的可以為世界做出貢獻,特別是對當今世界。我不知道,但「放下」這個詞似乎有很多犧牲的意思,是痛苦的。我本人不想犧牲任何東西。我覺得真正習慣了「自我在那兒,但也是不存在的」這樣更有好處,也更舒服,所以沒有什麼可放下的,這就是一種放下。我覺得這樣講更有好處。比如說,特別是年輕人,他們太喜歡酷了。酷、時尚、獨特,我覺得「我在那裏,但我又不存在」的想法真的可以幫助增強自信。我需要真正思考一下「放下自我」這句話,在我看來,這聽起來像是一種犧牲。是的,有些人也許喜歡犧牲。但爲什麼不改為看清真相呢?我覺得這其實是一種更好的犧牲。

“It’s there, but it’s not there” like the reflection of the moon in water

Q: If you wouldn’t mind me bring the microphone to my grandfather to ask a question?

問:如果您不介意,我想把話筒拿給我爺爺問個問題?

DJKR: Yes, please.

仁波切:好的,請。

Q: Hello Rinpoche, nice to see you back in Australia.

問:你好仁波切,很高興看到你回到澳大利亞。

DJKR: What happened to you?

仁波切:你怎麼了?

Q: I broke my foot just just two days ago in Bir. But speaking of appearing and disappearing and things coming and things going, I’m a little confused. How does one cook dinner or drive a car if things are appearing and disappearing?

問:我的腳是前兩天才在比爾摔斷的。但是說到出現和消失,說到物來物往,我有點困惑。如果事情持續地出現和消失,怎麼做飯或開車?

DJKR: I didn’t say things appearing and disappear. Not at all. I’m saying that while it’s appearing, it’s not there also i.e. at the same time. It is important you brought this up. There is a classic Buddhist phrase, “Like the reflection of the moon in water, it’s there but it’s not there”. I didn’t say that the moon disappears the moment you look at it, as if the reflection of the moon is shy. It’s there. Very intact. And it also actually has an order. You look at it. It’s there. Your granddaughter looks at it. It’s there. The two of you will further solidify that it is there.

仁波切:我並沒有說事情持續地出現和消失。完全不是,我是說,雖然它在出現,但它還是不存在。你提出來這個問題很重要。佛教有一個經典的詞「水中月」,如月在水中的倒影,似有或無。我沒有說,在你看到月影的那一刻,月影消失了,好像月亮的倒影很羞澀。它就在那裡,很完整地在那裡,而且它其實也是有秩序的。你看它,它就在那裏。你的孫女看着它,它也在那裏。你們兩個會進一步鞏固它在那裡的想法。

Q: But if it’s there one minute and not there the next minute?

問:但如果前一分鐘還在,下一分鐘就不在了?

DJKR: What do you mean by “next minute”? Like a cloud comes and it’s no longer there?

仁波切:你說的下一分鐘是什麼意思?比如說一片雲來了就沒有了?

Q: I guess. Isn’t that what you’re suggesting?

問:我想。你是不是有這樣的建議?

DJKR: No, actually I’m saying it’s there when there is no cloud, and then the cloud comes and also the reflection of the cloud, and there’s no more moon. All action is happening there. But it’s also not there. That’s all I’m saying.

仁波切:不是,其實我說的是沒有云的時候就有,然後雲來了,也是雲的反射,就沒有月亮了。所有的動作都在那裏發生,但又不存在。我說的就是這些。

Q: Thank you. Now I’m not there.

問:謝謝你。現在我不在。

DJKR: Somehow I’m not satisfied. I don’t think you have understood what I just said.

仁波切:不知爲何,我有點兒不滿意。我想你沒有理解我剛才說的話。

Q: Thank you.

問:謝謝你。

How do bodhisattvas help people with their horn and tail?

Q: Rinpoche, I had a question and then I listened to what you just said, and then that made me think of things, and that’s making me reconsider the question.

問:仁波切,我有一個問題,然後我聽了你剛才說的,然後讓我想到了一些事情,這讓我重新考慮這個問題。

DJKR: Okay. Very good. Cause and conditions.

仁波切:好的。很好。因緣嘛。

Q: Yes. So we have to get rid of hope and fear, which I guess is fundamental duality. But when there’s no hope and fear, what do we do?

問:是的。所以我們必須擺脫希望和恐懼,我想這是基本的二元對立。但是當沒有希望和恐懼的時候,我們該怎麼辦?

DJKR: We will be talking about this more during the so-called meditation and action. But I think maybe today since we are talking about the view, I think it’s important if you can think about “It’s there, but it’s not there”. Then it should give you some sort of release from both you hope and fear. It should really release you from blindly hoping or being blindly afraid of things.

仁波切:我們在談所謂的禪修和行為的時候,會更多地講到這個問題。但是今天既然我們在談見地,我想如果你能想到「它在那裏,但是它又不存在」,這是很重要的。它應該會讓你的希望和恐懼失去它們的立場,它應該真正地讓你從盲目的希望和盲目的恐懼中解脫。

Q: Okay, so the hope and fear and the normal motivations that make us do things are still there, but in that moment we can recognize it’s there but it’s not really there. It doesn’t affect you so much, but you still do things. You wake up in the morning and do all the normal things.

問:好的,所以希望和恐懼以及讓我們做事情的正常動機仍然存在,但在那一刻,我們可以認識到它的存在,但它並不真實存在。它對你的影響沒有那麼大,但你還是會做事情。你早上醒來,做所有正常的事情。

DJKR: Yes, very much. You watch the whole episode. Until the end.

仁波切:是的,就是這樣。你還是會看電視劇,並且從頭看到尾。

Q: Would that also apply to when we do bodhisattva activities, when we release other sentient beings from suffering? Is that also a story in the same way?

問:那會不會也適用於我們行菩薩道的事業的時候,當我們把衆生從痛苦中解放出來的時候?那是不是也是同樣的故事?

DJKR: Exactly. That’s what I’m saying. If you look at somebody you should even say, “Don’t worry”, even though it sounds so ridiculous. Try saying “Don’t worry” to somebody who has actually not taken any pills. Try saying “That’s how it is. Nobody has a horn. Nobody has a tail”. And yet you say “Don’t worry”.

仁波切:沒錯!這就是我想說的!如果你看着某人,你甚至應該說「別擔心」,儘管這聽起來很荒謬。你會試着對沒有吃藥的人說「別擔心」,你會試着說 「事情就是這樣。沒有人有角,沒有人有尾巴。」

Q: And we have to sort of convince everyone that they don’t have horns and tails? Is that what we’re trying to do?

問:我們要說服大家,他們沒有角和尾巴嗎?這就是我們要做的事情嗎?

DJKR: Are you talking about the bodhisattvas?

仁波切:你說的是菩薩嗎?

Q: Yes. That’s another action.

問:是的。這是另一個行為。

DJKR: What’s the question again? This is a tricky question. I better be careful,

仁波切:再說一遍你的問題是什麼?這個問題好像有坑,我最好小心點。

Q: Is the bodhisattva path about convincing everyone that they don’t have a horn and a tail?

問:菩薩道是否是要讓大家相信自己沒有角和尾巴?

DJKR: I see. Yes well, that’s one part of the homework, so to speak. That’s one part of it. But the bodhisattva is also courageous. Do you know why? Because actually there is no horn and tail. So bodhisattvas don’t have to go through life carrying a chainsaw. Because bodhisattvas think, “Actually there is no horn and tail. So it’s kind of a fairly easy job”. If people do have a horn and tail, then you are in trouble. There will be a lot of trash, especially if you’re a successful bodhisattva.

仁波切:我明白了。很好,這個問題可以作為今天家庭作業的一部分。菩薩是很有勇氣的。你知道爲什麼嗎?因爲事實上是沒有角和尾巴的。所以菩薩也不用拿着電鋸過日子。因爲菩薩知道,其實是沒有角沒有尾巴,所以這是一份相當輕鬆的工作。如果人家真的有角和尾巴,那你就麻煩了。特別是如果你是一個成功的菩薩,你就會創造很多垃圾出來。(眾笑)

Q: That’s very useful. It’s a bit like right now I feel slightly nervous talking in front of everyone, but not really nervous. It’s not actually there. Nothing bad can happen. It’s fine.

問:這非常有用。有點像現在我覺得在大家面前說話有點緊張,但不是真的緊張。事物並不存在,不會有什麼不好的事情發生。太棒了。

DJKR: Are you sure you haven’t taken anything?

仁波切:你確定你沒吃藥?(眾笑,鼓掌)

Game of Thrones, our body, and our consciousness are all “it’s there, but it’s not there”

Q: Rinpoche, firstly I want to thank you for your teaching today. I understand that the view of nonduality is the right view in Buddhism. How should we keep this view in our daily life? How can we maintain it? How can we keep it?

問:仁波切,首先要感謝您今天的開示。我的理解是,非二元的見地是佛教中的正確見地。我們在日常生活中應該如何安住這種見地?我們怎樣才能保持它呢?

DJKR: Yes, I think we will be talking more about this during the action. Are you coming tomorrow?

仁波切:是的,我想我們會在行為中更多地討論這個問題。你明天來嗎?

Q: Yes.

問:是的。

DJKR: Okay.

仁波切:好的。

Q: I’ll leave the question for tomorrow. I have another question. We all know you’re a very famous director, since I’ve been working in the film industry for years, I always find some kind of similarity between film and real life. And my question is, does that mean our real life can be a projection? Could it be a film projected by our consciousness?

問:我把問題留到明天再問。我還有一個問題,我們都知道您是一個非常著名的導演,因爲我在電影行業工作了很多年,我總能發現電影和現實生活有某種相似之處。而我的問題是,這是否意味着我們的現實生活也是一個投影?會不會是我們意識投射出來的電影?

DJKR: Yes, but first of all, I should say I’m not that famous. If I’m famous …

仁波切:是的,但首先,我應該說我沒有那麼出名。如果我很出名⋯⋯

Q: You are famous to me.

問:您對我來說很有名。

DJKR: Yes, I understand. It’s like a reflection of the moon. I’m known for making films that really put you to sleep. Anyway to answer your question about whether life could be seen as like a film. Yes, I think it can. But, you know, the interesting thing is sometimes when you write about your life, because the fiction is so well written, you forget that it’s fiction. It’s so good. Some really good writers can write amazing stuff and then you forget that it’s fiction. And I think that’s what is happening all the time. We write our stories so well that we forget that it’s not there. It’s there, but it’s not there.

仁波切:是的,我明白,這就像月亮的倒影。我以拍出真正讓你瞌睡的電影而聞名。總之,回答你關於生活是否可以被看作是一部電影的問題。是的,我認爲它可以。但是,你知道,有趣的事情是,有時當你以你的生活為素材來寫作, 因爲小說寫得如此之好, 你忘了這是小說。它是如此的好。一些真正優秀的作家可以寫出驚人的東西,然後你就會忘記了那是虛構的。而這就是一直在發生的事情。我們把我們的故事寫得很好,以至於我們忘記了它在又不存在。

Q: Does that mean our consciousness is also there, but it’s not there?

問:那是不是說我們的意識也在,但它不存在?

DJKR: Consciousness? Yes, it’s there, but it’s not there. But now you are going really far. I mean, you’re going really deep. With things like movies or Game of Thrones, we can say “It’s there, but it’s not there” and that is sort of understandable. You can buy that. But this? DJKR pinches his arm. Are we saying that my body is there but not there? Hmm. That’s much more difficult to chew. Much more difficult to accept. Now, what if we say that consciousness or mind is there, but it’s not there? That’s much more difficult to understand. And this is where I would say Buddhism has invested a lot of time and energy for two thousand years, to explain that.

仁波切:意識?是的,它在那裡但它又不存在。現在,你已經走得很遠了。我的意思是,你走得很深。對於電影或《權力的遊戲》這樣的東西,我們說「它在那裡但它又不存在」,還是比較好理解的,你可以接受的了。但這個呢?(仁波切捏了捏他的胳膊)我們是不是在說,我的身體在又不存在?嗯,這就難以下嚥得多,難接受得多了。現在,如果我們說,意識或心靈,在又不存在?那就更加更加難理解了。這就是我要說的,佛教兩千年來投入了大量的時間和精力,來解釋這個問題。

“It’s there, but it’s not there” in the traditions of Asanga and Nagarjuna

Q: Thanks for everything. It has been really good. I was reading a book by His Holiness and he was describing how Asanga introduced the mind-only idea because people were becoming too nihilistic with “no mind”. Is that view of Asanga a useful stepping stone for mere mortals like me? I find I can accept that “It’s there and it’s not there” quite readily if I have that mind-only view.

問:謝謝您所做的一切,非常好。我在讀尊者的一本書,他在描述無著菩薩如何引入「唯識」的思想,因爲人們變得太虛無主義,認為「唯物無心」。無著的見地對我這樣的凡夫俗子來說,是有用的墊腳石嗎?我發現,如果我有這種唯識的見地,我會更容易接受「它在那裏,它又不存在」的想法。

DJKR: Today, I tried to present the most important and the most difficult aspect of the view of Buddhadharma in a very short time. It’s very difficult. I will give you one example. You know, I said that the whole phenomenal world, everything, including consciousness, it’s there but it’s not there. And to establish this view and to dissect or decipher or really try to explain this, there are so many liturgies and so many different schools. In fact, you can sort of broadly say they are one actually. They are one. It’s a bit like a photography teacher. He can teach his student about shade. But at the same time, he’s talking about light, because they’re the same thing. But depending on what kind of student you have, maybe the student likes to dwell with shade more, so then you talk about shade and how to create shade. But simultaneously, you are also fiddling with the light. Just like that with another student, you talk about lighting, how to put light, but you are also creating shadow. It’s a bit like this. This is a really rough example. So in Buddhism also, in order to explain these two {i.e. it’s there and it’s not there, there is actually a whole set of commentaries written by a bunch of people like Nagarjuna. They are more concentrating and explaining the “It’s not there” part. And then there are the Asanga people, like the Yogachara people, who talk more about the “It’s there” part. And these differences in emphasis are not only found in Buddhist philosophical schools. Actually it has also influenced society. If you go to Tibet, the Tibetans are more into these Nagarjuna people. So they talk about emptiness a lot. But if you go to China, especially the later great Zen masters, I suspect they may be talking more about the “It’s there” part. Thus you have things like the Pure Land School, Lotus Sutra, and so forth. But these two traditions are both so important, like the light and the shadow.

仁波切:今天,我試圖在很短的時間內,把佛法的見地中最重要、最困難的方面介紹出來,這是非常難的。我舉一個例子,我說,整個現象界,一切的一切,包括意識,在又不存在。而要建立這個見地,要剖析要解讀,或者真正的試圖解釋這個問題,有這麼多的儀軌,有這麼多不同的學派。事實上,你可以說它們大致上是一個,是一體的。這有點像攝影老師,可以教他的學生什麼是陰影,但事實上是,他也在講什麼是光,因爲它們兩是同一個東西。但這要看你有什麼樣的學生,也許學生更喜歡和陰影打交道,所以你就講陰影,講如何創造出陰影來。但同時,你其實是在擺弄光線。而對於另一個學生,你講燈光,如何擺放燈光,但你也在創造陰影。這有點像這樣,這是個很粗略的例子。在佛教裏也是,有一套完整的註釋,是由龍樹等一幫人寫的,他們對「它不存在」這部分的解釋比較集中,也比較詳細。還有一些人如無著,他們被稱為瑜伽行派(譯:提問者所問的唯識派,就是這裡說的瑜伽行派),他們更多的是在講「它在那裡」的部分。而這些側重點的不同,不僅存在於佛教哲學流派中,其實也影響了社會。如果你去西藏,藏族人更喜歡龍樹那些人,所以他們經常講空性。但是如果你去中國,特別是佛教發展後期的各位大禪師們,我猜想他們可能更多的是講「它在那裏」的部分。於是你就有了淨土宗、法華經等東西。但是這兩個傳承都是那麼的重要,就像燈光和陰影。

If we really know “it’s there, but it’s not there”, we can take a break from our ordinary life

Q: Dear Rinpoche, in the beginning you said that enlightenment is about getting rid of something. So, do you mean that “getting” is like more like “It’s there” and “getting rid of“ is more like “It’s not there”?

問:親愛的仁波切,一開始您說,開悟就是要祛除一些東西。那麼,您的意思是不是,「得到」更像是「它在那裏」,而「祛除」更像是「它不存在」?

DJKR: I was talking more about the result, the aim of Buddhadharma. Contrary to a lot of people’s way of expressing the goal of Buddhism as to “Achieve enlightenment, get enlightenment”, you know, “You get something”. But actually, the Buddhist aim, nirvana or the result, is more defined by what you get rid of. That’s why I was saying you don’t need to get a head. What you need to do is get rid of the delusion of the horn.

仁波切:我說的更多的是結果,佛法的目標。很多人把佛法的目標表述爲「成就覺悟,得到覺悟」「你得到了什麼」,與之相反,實際上佛教的目標,涅槃或佛果,更多的是由你祛除的東西來定義的。這就是爲什麼我說你不需要得到一個頭,你需要做的是祛除有角的妄想。

Q: So one is result and one is view and they’re not so connected?

問:所以一個是果,一個是見地,它們之間沒有那麼大的聯繫?

DJKR: No, the result is when you are free from this delusion. That’s the result. So if somebody asks you “Are you Buddhist?” “Yes” “What do you believe in?” “It’s there but it’s not there”. Actually that will drive them nuts. But that’s how it is. Of course the safest answer if you are at a Christmas party or a Chinese New Year party is to say, “Oh, Buddhists believe in vegetarianism. Buddhists believe in smiling. Buddhists believe in nonviolence. Buddhists believe in karma and reincarnation”. Yes, I think that will do. But actually you should be saying, “You know, Buddhists believe that all things are there, but they’re not there”. But I don’t think anybody will like you for that. Okay, the second question, if they ask you “Okay, so what are you aiming for? What do you get?” Then you say, “We don’t get anything. We only get rid of things”. That’s what your answer should be, actually.

仁波切:是的,當你從這個妄想中解脫出來,就是果。所以如果有人問你「你是佛教徒嗎?」「是的」「你的信仰是什麼?」「它在那又不存在」,這樣的回答會把他們逼瘋的。但確實就是這樣。當然如果你是在聖誕晚會或春節晚會上,最安全的回答是:「哦,佛教徒信素食。佛教徒信應該微笑。佛教徒信非暴力。佛教徒信因果報應和轉世輪迴」。是的,這樣是可以的。但其實你應該說:「佛教徒相信,萬物皆在那裡,但他們又不存在」。但我不認爲有人會因此而喜歡你(眾笑)。好,即便如此,如果他們問你第二個問題:「你們的目標是什麼?」然後你說,「我們什麼也得不到,我們只祛除東西。」你一定要這麼回答,真的。

Q: And as you answer the other person’s question by saying “It’s there but it’s not there”, can that still help people to cultivate confidence?

問:假設你回答對方的問題時說「在那但不存在」,這能幫助人們培養信心嗎?

DJKR: Yes.

仁波切:能。

Q: How how does it work? That’s my question.

問:為什麼能?這是我的問題。

DJKR: I gave you the example already. When you are watching TV. Why do you have the confidence to go to the toilet if you need to go? Because you know that the TV program is there, but it’s also not there. If you don’t have one of those two aspects of the view, then you don’t have that confidence. You won’t have the confidence, because you think it’s there or it’s not there.

仁波切:我已經給你舉過例子了。當你在看電視的時候,如果你需要上廁所,爲什麼你有信心去上廁所?因爲你知道電視節目在那裏,但它不是真的。如果你不是同時擁有這兩個方面的看法,那麼你就沒有這個信心。你要麼就是非得看完,要麼就是完全不看。

Q: Like it’s there in 2-D but it’s not there in 3-D? Can we use that?

問:比如二維的時候有,三維的時候就沒有了?可以這麼說嗎?

DJKR: What?

仁波切:什麼?

Q: I mean in the screen it’s there but …

問:我的意思是在屏幕上是有的,但是⋯⋯。

DJKR: In reality it’s not there, right? That’s why …

仁波切:現實中是沒有的吧?這就是爲什麼⋯⋯

Q: We have the confidence to go to the toilet.

問:我們有信心上廁所。

DJKR: Yes. So just like that, if something is happening in your life which is really bothering you, if you can really habituate yourself to this view. If you can really realize that whatever you are valuing, whatever you are putting so much effort into is actually there, but it’s also not there. Then you can take a break from your life.

仁波切:是的。所以就這樣,如果在你的生活中發生了一些真正困擾你的事情,如果你真的能讓自己習慣於這種見地。如果你能真正意識到,無論你在珍視什麼,無論你在付出多少努力,其實都是在那的,但又不是真的。那麼你就可以從你的生活中解脫出來。(鼓掌)

We think too much

Q: Rinpoche, do we just think too much?

問:仁波切,我們是不是想太多了?

DJKR: Yes, that’s why I’m going to end it soon.

仁波切:是的,所以我很快就會結束。(眾笑)

Q: Thank you.

問:謝謝。

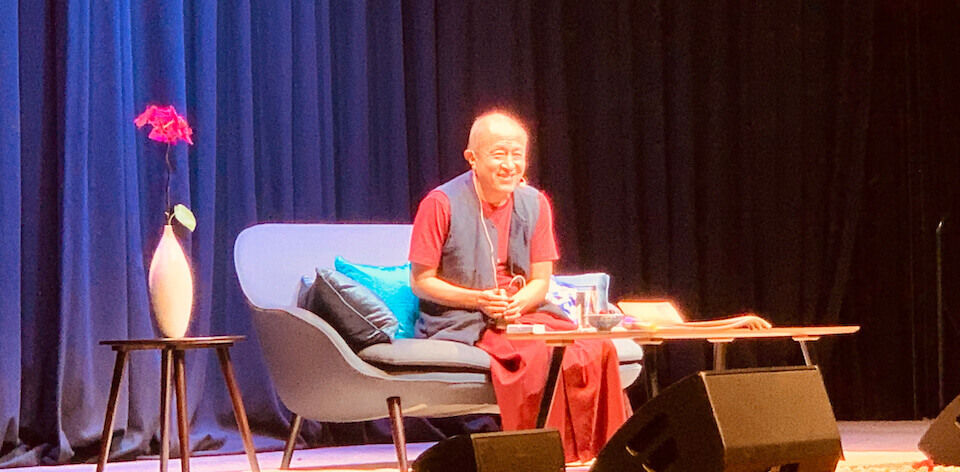

宗薩欽哲仁波切,於 2020年1月25-27日(農曆新年)在澳大利亞悉尼的新南威爾士大學,給予了為期三天的教授,題目為《見修行》。英文部分由 Alex Li Trisoglio(仁波切指定的佛法老師)聽寫,並分段和添加標題,發布在 Madhyamaka.com。中文部分由 孫方 翻譯。並在翻譯過程中,根據視頻做了文字上的修訂,所以中英文部分可能會有可忽略不計的微小差別。照片為課程現場。