譯者按:頂禮本師釋迦牟尼佛!恕譯者才疏學淺,未明心要,謬誤在所難免,僅供參考。所譯文字未經上師認可,或專業翻譯機構校對,純以個人學習為目的,轉載或引用請慎重。

Recap of the view: the four seals

So, not to lose our thread or the context, we have talked about the view, meditation, action and result. And yesterday we talked about the result being not so much to do with “getting”, actually not at all. It’s more to [do with] “clearing” or getting rid of. That’s what we are aiming for. It’s like washing a cup. When you wash a cup, you’re not trying to make or get a new cup. You are washing the dirt. It’s like that. So for that, we need to apply a path in order to gain that result. It’s automatic, but we have to talk like this [even though the result is about elimination rather than gaining]. To reach to that result, maybe that’s a better word, to reach to this result, we apply a path.

繼續我們昨天的主線,我們已經談了見、修、行、果。昨天我們談到了佛教的果與 「獲得什麼」沒有太大關係,實際上根本沒有。它更多地與「清除」或「擺脫」有關,這就是我們的目標。這就像洗杯子,當你洗杯子時,你不是要製造或得到一個新杯子。你是在清洗汙垢。為此,我們需要應用一條法道,以「達到」那個結果。達到是一個更好的詞。

A path consists of three almost indispensable attributes or aspects. (1) The view that we have talked about is very, very important. (2) And then practice or meditation. (3) And then action. Just to recap, the view is presented in many different ways, but one very popular [way] is the relative view and the ultimate view. To extend this a little bit, the relative view is sometimes presented in terms of what we call “the four seals”:

一條法道包括三個不可缺少的屬性或方面。(1) 我們談到的見地,這是非常非常重要的。(2) 然後是禪修。(3) 然後是行動。回顧一下,見地是以許多不同的方式提出的,其中一個非常流行的方式是相對見地和究竟見地 (譯:勝義諦和世俗諦) 。稍微延伸一下,相對來說,見地有時是以我們所說的「四法印」的方式呈現。

All compounded things are impermanent.

All defiled emotions or all emotions are pain.

All phenomena have no truly existing nature.

Nirvana or Enlightenment is beyond extremes.

一切和合事物皆無常。一切染污或說一切情緒皆苦。一切現象沒有真實存在的本性。涅槃或說証悟超越了一切極端。

So especially in the Mahayana, this how the view is presented. But I think we [have] talked enough about the view.

這就是見地,特別是大乘的見地。我們已經對見地談得夠多了。

To qualify as Buddhist, a meditation or practice must go against dualistic mind

Now, [let’s turn to] “meditation” or “practice”. First I want to tell you this. To qualify [as] a Buddhist practice, any meditation or practice, whatever it is, must go against dualistic mind. That’s what the practice is for.

現在,讓我們談談禪修。首先,我想告訴你這一點,為了成為佛教的修行,任何禪修,都必須以反對二元對立作為修行的目的。

In today’s world, meditation has become very trendy. There are even several meditation apps. Now based on this [criterion], if you think about it, most of the meditation that is being taught, practiced, and marketed – even the so-called vipassana, which is used by a lot of people – is not really aiming to defeat duality, is it? If that [was really the aim], the app developers wouldn’t have a business. It’s really the opposite. Meditation is to make you feel relaxed. To free you from stress. To energize you. And so forth.

在今天的世界裡,禪修已經變得非常時髦。甚至有幾個禪修 APP。但如果要基於這個標準,你仔細想一想,大多數被教授、被練習、被推銷的禪修,以及很多人所謂的內觀,並不是真的以打敗二元對立為目的,不是嗎?如果是以這個為目的的,APP 開發商就不會有生意了。它實際上是相反的,禪修是為了讓你感到放鬆,把你從壓力中解放出來,讓你精力充沛,等等等等。

This is where stakeholders [i.e. masters and lineage holders] really have to be careful. I was joking with an Indian yoga teacher. He’s a really good yoga teacher, actually. I think he’s one of those last remaining authentic yoga teachers. I told him, “It’s too late now. Yoga is gone. Finished”. It has become [its own] separate phenomenon. It’s like the whole purpose of yoga, the view of yoga, and even a lot of action or the technique itself has become like the Mexican food served in America. Or like a ramen shop run by the Chinese in Sydney. Yes, it does look like ramen. But it’s not really ramen. And in the modern world, the packaging is what’s attractive. So the packaging takes over.

這就是各位上師們和傳承持有人們真正要小心的地方。我和一個印度瑜伽老師開玩笑。事實上,他是一個非常好的瑜伽老師。我認為他是最後剩下的那些正宗瑜伽老師之一。我告訴他「已經太晚了,瑜伽已經失傳了,完蛋了,它已經成為了另一個東西。」整個瑜伽的目的,瑜伽的觀點,甚至很多動作或技術本身已經變得像美國的墨西哥食品,或者像悉尼的由中國人經營的日式拉麵。是的,它看起來確實像拉麵,但它並不是真正的拉麵。而在現代世界,包裝才是唯一有吸引力的,所以包裝佔據了主導地位。

The meaning of meditation and mindfulness

So let’s go through this little bit more. [What we mean by] practice or meditation. Because the word dhyan, chan, zen, gom in Tibetan is really about getting used to and getting accustomed to. [Getting accustomed] to what? [It is] to get accustomed to the view that we have been talking [about for] one and a half days. That’s what it is for.

因此,讓我們再來看看這一點,什麼是我們所說的實修或冥想。因為梵文的「狄安」,中文的「禪」,日文的 ZEN,藏文的「貢」這些詞指的是「習慣於某事」。習慣於什麼呢?就是習慣於我們已經談論了一天半的見地,這就是它的作用。

You can’t possibly think that sitting straight is our [purpose or] end. How can you think that? That would be so easy. Just put a stick [to keep] your spine [straight]. You can’t possibly think that sitting on a cushion is the end. [You can’t possibly think] that [this] is what Buddhists are aiming for. And anyway, we have to be careful about using the word and the language “mindfulness”, because mindfulness has the connotation of being careful. Mindful as in “Beware, be mindful”. Really? Is that how you want to exhaust your life, [by spending] your whole life being careful? That doesn’t sound at all good, does it? Panicky all the time, mindful?

你不可能認為坐直是我們的目的。你怎麼能那樣想呢?那就太容易了,只要放一根棍子保持你的脊柱挺直。你也不可能以為坐在墊子上就是目的,是佛教徒所追求的目標。而且,我們必須小心使用「正念」這個詞和語言,因為正念有細心的意思。正念的意思是「要小心,要用心,要仔細」。真的嗎?你想這樣終其一生,就僅僅是變得更細心?這聽起來一點都不好!這樣好嗎?總是神經質地小心翼翼?

Whatever method takes you closer to the truth – I have to repeat this again and again – that is the path. That is meditation. Now having said all of this, of course, sitting straight or isolating yourself from your kitchen to the living room, or from your living room to the shrine room, or from your house to a mountain, or from the city to a under a tree in the forest – all these have been prescribed and encouraged by the masters of the past, because they do have benefit. Yes, the chance of you getting closer to the truth, closer to the view, is higher by you sitting straight than by lying in a hammock. Probably. For a lot of people. But also [there is the risk of] spiritual materialism. “How many hours I could sit? How straight can I sit?” Those can also be a very big distraction.

我必須一再重複這一點:無論什麼方法,只要能讓你更接近真理,那種方法就是道,就是真正的禪修。現在說了這些,當然,正襟危坐,並把自己限制在客廳不去廚房;或把自己限制在佛堂不去客廳;或把自己限制在深山,不住在房子裡;或把自己限制在一棵樹下,遠離城市。所有這些被過去的大師們規定和鼓勵的方法,確實是有好處的。坐直比躺在吊床上更有可能接近真理,接近正見,對很多人來說是的。但也有「修道唯物主義」的風險。我需要坐多少個小時?我可以坐得多直?這些也可能是一個非常大的分心散亂。

Any practice can be considered vipassana if your motivation is to see the truth

[Let’s talk about] the word “vipassana”. Vi- in Pali is “suchness”, “that”, “that which is”, “the real thing”, “the real deal”, “the real McCoy”, “the true color”. Passana is basically getting used to that. Getting used to it. So, in this sense, it is not wrong to consider what we did yesterday, [with me] talking like this and you listening, [as we are doing] now, it’s not wrong to also consider this a vipassana session. Especially if you come with the motivation, “I want to know the truth. I want to meet the real McCoy. I want to see the real color. I have been distracted and entangled too much by all kinds of fake things. I want to see the truth”. If you come here with that motivation, and [the motivation to] decipher and pull the rug out [from] this solid duality, then even listening, debating, and reading can be easily considered as vipassana.

讓我們來談談 Vipassana 這個單詞。Vi 在巴利語中是真實的意思,「就是那個」「真實的東西」「本色」。Passana 基本上是「習慣於此」。所以,在這個意義上,把我們這幾天的這種「我說你聽」也算作 Vipassana,絕對是沒錯的。特別是如果你帶著這樣的動機來:「我想知道真相。我想看到事物的本色。我已經被各種假的東西分心和糾纏得太多了。我想看到實相。」如果你帶著這樣的動機來到這裡,並且希望破譯,希望抽走堅實的二元對立的地毯,那麼即使是聆聽、辯論和閱讀也應該被視為 Vipassana。

And now think about it. [What about] offering flowers to a temple [with the aspiration] “With this, may I see the view”. Burning incense. Rituals. Going to a temple. Shaving hair. Changing robes. All this is an act of Vipassana. It is. But [how does this look to a] modern, skeptical, scientifically-minded person? [Someone who] has the residue of Abrahamic religious thinking? “What are you doing? Flowers? Incense? That’s Indian and Tibetan stuff. And it’s a ritual. It’s not scientific. It’s shamanist stuff”. But when it comes to sitting, especially if you’re British, “Oh this is jolly good. This is harmless”. So you feel comfortable with that. Which is fine. If that is what you are comfortable with, you should do that. But there are people who never, ever sit. All they do is chant mantras and [turn] prayer wheels. The whole time. All they do is [turn] prayer wheels and chant mantras, but their motivation is to see the view. Those [methods] should not be discarded. They’re very important. Really good.

現在想一想。當你在寺廟供花的時候,能想到「通過我的供養,願我能了悟見地」;或同樣地,在燒香的時候;做儀軌的時候;去寺廟出家,剃除頭髮,更換長袍的時候,如果能這樣想,所有這些都是 Vipassana 的一種行為。但是,對於一個現代的、持懷疑態度的、有科學意識的人來說,尤其當他的亞伯拉罕宗教思想殘餘,和他的科學意識碰撞到一起的時候,他會說「你在做什麼?鮮花?香?那是印度和西藏的東西。這只是儀式,這是不科學的,是類似薩滿教的東西。」但是當他涉及到打坐,尤其是對於英國人而言「打坐是很好的,是無害的」。其實這是好事。如果這是你覺得舒服的事,你應該這樣做。但是有些人從來從來沒有打坐過,他們一輩子所做的,就只是持誦咒語和轉經輪 (譯:仁波切的手在比劃轉經輪) ,但他們的動機是為了了悟見地。那這些方法就不應該被丟棄,它們非常重要,真的很重要。

Whereas even meditation is not a spiritual path if your motivation is for a better samsaric life

You know, I belong to this second department. I just can’t sit, because it’s so boring. Yes, maybe for 10 or 20 minutes once in a blue moon. But I love my shrine. I love these flowers and incense. It moves me. It makes me almost teary. Sitting. It’s boring to me. I belong to this [second group]. This is really important you know, and this is why motivation is so important. If your motivation in doing vipassana is so that you can have better sleep, so that you can be stress free, so that you get energized, so that come Monday you [can] be ruthless in destroying the earth by doing all sorts of business, [then you’re] not really following a spiritual path. Your vipassana has become just another gadget to make your life quicker, faster, more profitable, etc. It’s just like a fax. Or like a laptop. It’s like a vacuum [cleaner]. Your vipassana has become a household appliance. Like blind or shades [for your windows]. Or it has become like a massage.

你知道,我屬於這第二類人。我就是坐不住,因為太無聊了。是的,也許偶爾會坐10或20分鐘。但我愛我的佛堂,我愛這些花,這些香,它們讓我感動,讓我流淚。這就是為什麼動機是如此重要。如果你做 Vipassana 的動機是為了讓你有更好的睡眠,讓你沒有壓力,讓你得到能量,讓你在週一的時候可以通過做各種生意來無情地摧毀地球,那麼你就不是真正在走一條精神之路。你的 Vipassana 已經成為讓你的生活更快、更方便、更富裕的另一個小工具,等於一台傳真機,或一台筆記本電腦,一個真空吸塵器,一個家用電器,一個百葉窗,或者是像一次按摩。

I’m not saying you should not do that. Of course, please buy as many household appliances as possible, and have as many massages as possible. And yes, along with that you can do meditation if you want. But you need to know the view. And anything that takes you closer to the view, even if it means a heated argument with somebody, if that’s taking you closer to the view, you are a fortunate being. Your life has become worthwhile. So with that in mind, if you look at the recipe of the classic vipassana you will understand what I’m talking about. Basically the classic recipe, on the most fundamental level of Buddhadharma, has three ingredients of vipassana. Three characters [Ed.: characteristics]. I think sometimes they call it three marks. Anicca, dukkha and anatta.

我不是說你不應該這樣做。當然,請盡可能多地購買家用電器,並盡可能多地去按摩。也就是說,如果你願意,請盡可能多地打坐。但是你需要了解見地。任何能讓你更接近見地的事情,即使是與某人發生激烈的爭論,如果這能讓你更接近見地,你就是一個幸運的人,你的生命已經變得有價值。所以,考慮到這一點,如果你看一下經典的 Vipassana 的配方,你會明白我在說什麼。在佛法的最基本層面上,Vipassana 有三種成分,我想有時他們稱之為三個標誌:無常(Anicca)、苦(Dukkha)、無我(Anatta)。

(1) Anicca (impermanence)

Anicca is probably the most easy to chew. It’s good to begin with. Anicca is impermanence. That is the truth. Impermanence. That is a raw truth. It’s not mythical, it’s not religious, it’s not a revelation. It’s the raw, blatant, obvious, ridiculously here-and-now truth. Change. Impermanence. But again, here we have to be careful. Many people always end up thinking, “Oh, Buddhism [talks about] impermanence. [It’s] the harbinger of the bad news. Buddhism always talks about death and impermanence.” Well, I have to sort of blame this on the lamas and especially on the monks and nuns, because that’s one of the tricks [used in monasteries] to make them practice the Dharma more. But actually, impermanence is not just that. Impermanence is not only bad news. It’s also good news. Because of impermanence, you can do lots of things. There is hope. Thanks to impermanence, things change. This is [something] that you need to know.

無常,可能是這當中最容易咀嚼的。無常是個很好的開始。無常是真相,是一個很原始的真理。它不是神話,不是宗教,不是啟示錄。它是原始的、公然的、明顯的、可笑的現世真相。但同時,在這裡我們必須要小心,許多人總是在想,佛教所說的無常是壞消息的預兆,佛教總是在談論死亡和無常。好吧,我不得不將此歸咎於喇嘛們,尤其是比丘和比丘尼們,因為這是一種督促人們多從事修行的技巧。但實際上,無常並不只是這樣。無常不僅是壞消息,也是個好消息。因為無常,你可以做很多事情,你有更多希望。由於無常,事情會改變,這是你需要知道的。

So [perhaps you will] go to a cosmetic shop today and buy moisturizer. Yes, by all means, you must buy moisturizer. It’s really important, even according to Shantideva, the Mahayana master, who [compares the] body to a servant:

舉個例子,假如今天你要去化妝品店買保濕霜。這真的很重要,甚至按照大乘法師寂天的說法,他把身體比作一個僕人。

You know, you have to pay a wage to your slave. It’s a salary. Yes, pedicure, manicure. Please. You must do whatever. Shampoo, grooming, whatever. You must do it, by all means. But today when you do it, [try to do it with] this idea that “Yes, but you know, it’s just inevitable that it’s going to change.” Not necessarily getting old, by the way. But it’s going to change. Change, anicca, impermanence. So when you buy hand cream, as you pay for it, think “Yes, it will help a little bit, but while it’s moisturizing, it is also dry.” While it’s becoming more the foundation, [all the] while it loses … [Ed.: DJKR doesn’t complete the thought].

你必須向你的僕人或奴隸支付工資,買保濕霜是一種工資。是的,腳趾護理,手指護理,洗髮,護髮,所有這些,請你儘管去做。但是,今天當你做這些的時候,試著用這種想法去做:「身體是不可避免地要改變。」不一定是變老,它只是會改變。無常就是改變。因此,當你買護手霜時,當你付錢時,要想:「它會有一點幫助,雖然它是保溼的,但手還是會乾燥。」 (眾笑) 希望這能成為一個基礎的想法。

Buying moisturizer and the Seven-Eleven vipassana

If you have that, yes, it’s a Seven-Eleven vipassana. It is, really. I have the backing of all the scholars and saints of the past, I’m serious. I’m not making this up. That is a vipassana. I would rather you go to a grocery shop and buy food and think, “It is possible that I may never eat this food”. I would consider that a much more profitable or rewarding vipassana than hours and hours sitting on a cushion [without this view of anicca] and getting really bored and in pain and whatever. It’s so important that you know this.

如果你有這個想法,這就是一次 7-11 Vipassana。真的真的,我有過去所有的學者和聖人的支持,我是認真的,這不是我編的。這是一種 Vipassana。我寧願你去雜貨店買食物的時候想:「我有可能吃不到這個食物。」我認為這是一個更有利或更有價值的 Vipassana,而不是幾個小時坐在墊子上,那將變得非常無聊和痛苦。知道這一點是非常重要的。

Similarly, [suppose] you are depressed, you’re really not happy. You’re sad. You’re really feeling hopeless. Then also [you might] tell yourself, “How many times have I been sad in the past? How many times? Just so many, and none of them stayed”. Yes, some of them sort of lingered a little bit, but there are a lot of times you are happy. Many times, I’ve seen some of you depressed people. I’ve seen with my own eyes, you had good times. Many times. So that’s possible. It’s, “Okay, this morning I’m not so happy. But it’s very possible this afternoon that I’ll be happy”. Like that. That is really getting closer to anicca. That is getting closer to the view. That is practice. It’s so important that you know this.

同樣地,假如你是抑鬱症患者,你不快樂,你很悲傷,你真的感到很無助。那你也可以告訴自己:「過去我有多少次悲傷?有多少次?這麼多次的悲傷,但沒有一次能長久保留下來。」是的,其中一些有點徘徊不前,但你也有很多快樂的時光。很多時候,我看到你們中的一些人很抑鬱,但我也親眼看到你們有過美好的時光。「好吧,今天早上我不是很開心,但下午我很有可能會很高興起來。」像這樣。這真的是越來越接近無常,越來越接近見地。這才是佛教所說的實修。知道這一點是非常重要的。

This culture, this kind of thinking and attitude is important. Because I think many times we wrongly measure “Oh, he or she is a great practitioner”. What does that mean? [Are you simply saying that] he sat for many, many hours? We don’t know. I would like to hear a day when some Australians say about other people “You know, he’s a great practitioner. Every time he goes to Seven-Eleven, or every time he buys a moisturizer, he thinks about how while it’s dry, it is also moisturized”. You understand? That’s a good yardstick or indicator of how you define practice.

這種文化,思維方式和心態是很重要的。我認為很多時候我們使用了錯誤的衡量標準。「他或她是一個偉大的修行人。因為他打坐了很多很多個小時。」什麼意思呢?我們說不準。而我想聽到的是,有一天,一些澳大利亞人對其他人說:「嘿,他是一個偉大的修行人,因為每次他去 7-11,每次買保濕霜,他都會想到乾燥和保濕是不二的。」明白嗎?這是一個很好的衡量標準,來定義實修。

Change is the truth, but we try to forget it and cover it up

That’s anicca. Change. Change is the truth. Change is a view. But as blatantly obvious as it is, it’s difficult. Again, yesterday we talked about our habitual patterns. Yesterday, the Chinese should all have cried for New Year because it means they’re getting old. In about a month’s time, all the Tibetans should cry for having their New Year. Every time your birthday comes, you should mourn. You should wail, “Oh, tomorrow my birthday is coming. I’m getting old”. But we don’t think like this. We cover it up.

這就是無常,無常就是變化,變化是真理,變化是見地,儘管它是如此露骨,但它仍然是難以接受的,就像昨天我們談到的習氣模式。昨天,所有的中國人應該為過新年而哭泣,因為這意味著他們正在變老。大約一個月後,所有的西藏人也應該為過新年而哭泣。每次你的生日到來時,你都應該哀悼。你應該哀嚎:「哦,明天我的生日就要到了。我正在變老。」但是我們不這樣想。我們把它掩蓋起來。

It’s the same thing [with] all our plans, scheduling, diary books. In Singapore airport I saw a diary book for the year 2021. It’s already on sale. Shocking isn’t it? A 2021 diary book. Actually, at that time I thought “Wow, will I ever see this year 2021?” So there is that habit of eternalism or permanence, [which is the opposite of] annihilation. Permanence. It exists. We have that. So, yes, as blatantly, simply, and obviously that this truth is so ever-present, it doesn’t mean that we dwell on it. Actually we do all kinds of things to forget it. That’s what samsaric beings do. We try so hard to forget the truth.

這和我們所有的計劃、日程安排、日記本是一樣的。在新加坡機場,我看到一本 2021 年的日記本,已經開始銷售了。令人震驚,不是嗎?當時我想「哇,我還能看到 2021 這一年嗎?」所以,我們有永恆主義的習氣(或叫常見,與虛無主義/斷見相反的),持久性、存在性的習氣。所以,即使如此露骨的、簡單的、明顯的、永遠正確的真理,但這並不意味著我們能接受。事實上,我們做了各種各樣的事情來忘記它。這就是輪迴眾生所做的,我們非常努力地想忘記這個真相。

Our so called samsaric living is that. To tell ourselves as many lies as possible, to constantly live in denial. That’s how it is. So [facing the truth of impermanence] is actually a good beginning to [practicing or meditating on] the view that we have been talking about yesterday and this morning. Impermanence is not a bad word. I think this will do [as a translation of “anicca”].

我們所謂的輪迴生活就是這樣。儘可能多地告訴自己謊言,不斷地生活在否認之中。所以無常實際上是我們昨天和今天早上一直在談論的見地的一個良好開端,無常並不是一個壞詞。

(2) Dukkha (unsatisfactoriness)

Now the next one is much more subtle, much more profound, and probably much less blatant and obvious. Dukkha. [It is sometimes translated as]“suffering”, but this word is really not good. I think the Thai and the Burmese have managed to translate this as “unsatisfactoriness” or something like that. Probably that’s better than “suffering”. There should be a Buddhist conference where we discuss this.

下一個問題要微妙得多,深刻得多,而且可能不那麼露骨和明顯。那就是「苦」。它有時被翻譯成「受苦」,但這個詞真的不好。我想泰國人和緬甸人已經設法把它翻譯成「不滿足感」或類似的東西。可能這比「受苦」要好。應該為此專門開個佛教會議。

I think the word “suffering” that the Buddhists have been using is not only misleading, but it has also really done damage to Buddhism. No-one wants to hear Buddhadharma, because they think that Buddhism is going to talk about suffering. The truth of suffering. Right at the beginning, they hear the truth of suffering. Who wants that? Try to talk to teenagers, they all want to have fun. And they think they’re having fun. And many of them actually are [having fun].

我認為佛教徒一直使用的「受苦」這個詞不僅有誤導性,而且對佛教確實造成了損害。沒有人願意聽佛法,因為他們認為佛教要談的是「受苦」。如果佛法的教授始於「苦諦」,誰想聽這個?你試著和青少年談談,他們都想要快樂,而且他們認為他們在玩樂,而且許多人確實也很快樂。

We’re not in Syria. We’re not fighting in a war. There’s the next app to download. There’s the next episode to look forward to. Nice coffee shops. There’s a nice beach. I’m fairly okay, sort of healthy. Yes, sunsets. That’s kind of nice also. Sunrise. And we can sleep. We have nice beds. We have a lot of good soft music. A lot of jazz music. Night life. Wow. These things are all good. So I think the word “suffering” is not right. Dukkha is a very good word, by the way, I think Sanskrit is actually such an important language. I found out that Sanskrit has 72 words for “love”. What a great thing, isn’t it? So good. Love. I’m sure the Latin language is as rich.

我們不是在敘利亞,我們沒有身處戰爭,我們永遠有 APP 等著我們去下載,有下一集電視劇可以期待,有漂亮的咖啡廳,有漂亮的海灘。我過得還好,算得上健康。我們有不錯的夕陽可以看,有日出。我們可以睡得著,我們有漂亮的床,我們有很多好的輕音樂,有爵士樂,有夜生活。哇喔,這些東西都是好的,所以我認為「受苦」這個詞是不對的。梵文中的苦,就是一個非常好的詞。順便說一下,梵文是一種如此重要的語言,我發現梵文有 72 個表達愛的詞。多麼偉大的事情,不是嗎?我相信拉丁語也一樣豐富。

Anyway, dukkha has something to do with unsatisfactoriness. It’s never satisfying, is it? Freedom of speech is never satisfyingly free. Democracy is never satisfyingly democratic. Fashion, food, technology, everything. Beach house. Also the word dukkha has the connotation of what in Tibetan we call tsimpa mepa. We just never come to that day of “Okay that’s it”. Conclusion. It’s always work in progress. We have never really lived one hundred percent as we planned. And then suddenly your children will have their children, and then you have to act like a grandparent. And you’ll be happy. Yes, [being a] grandparent is good. Grandchildren. But things have begun now. So, [it’s] never ending. As the Sakyapa master Drakpa Gyaltsen said:

總之,苦與不滿足感有關。我們永遠不會滿意,不是嗎?言論自由從來不是令人滿意的自由,民主從來不是令人滿意的民主,時尚,美食,科學技術,海邊小屋,等等一切。另外,苦這個詞的內涵是(在藏語中我們稱之為「清帕邁帕」),我們永遠也不會走到完美的那一天,永遠不會蓋棺定論,事情總是完成了一半,我們從來沒有真正百分之百地按照我們的計劃生活。突然間,你的孩子有了他們的孩子,然後你要開始當爺爺奶奶了。也許你會很高興,爺爺奶奶孫子孫女這樣,挺好的。但是,事情就是這樣開始了,並且永遠不會結束。

Our whole life is spent preparing

It’s always arrangement. Preparation. We’re always preparing for the next thing. Life is just preparation after preparation. So the real pleasure or [real] life has never really arrived as we wished. And even though it may arrive momentarily, because of its uncertainty there is unsatisfactoriness. That’s what dukkha is all about.

正如薩迦派大師札巴堅贊 (譯:薩迦派第三祖) 所說:「我們總是在為下一件事做準備。」生活只是一個又一個的準備。因此,真正的快樂,真正的生活,從未如我們所願般到來。即使它暫時到來,因為它的不確定性,仍然會有不滿足感。這就是「苦」的全部內容。

And again, as I’m presenting this, I think I have presented it in sort of a negative way, but it should not be negative. It can be very fulfilling and rich. And amazing. Maybe I’ve got the wrong idea about this, but I made a new friend He’s really very wealthy, and it made me think a lot. He has no house. And he also doesn’t really rent a place. So he always stays in hotels. He must have stayed in several hundreds or thousands of hotels. And always really good hotels too. He comes here also, he stays in The Rocks. And also he doesn’t stay in big rooms. You know how some hotels have big rooms and several rooms [together in a suite]? No, [he just stays in] a standard room. And I was asking why [does he live] like that. He said “Oh, this is much more satisfying”. Because, he said he doesn’t have to hire a maid. The hotel has maids. And also he shops much less, because the hotel room doesn’t have much room to store his shopping. Stuff like that. It’s quite good, isn’t it?

當我這麼說的時候,我想我是以消極的方式在說,但它不應該是消極的,它可以是非常充實的,豐富的,令人驚訝的。最近我交了一個新朋友,他真的非常非常富有,有件事我想了很久:他沒有房子,而且他也不怎麼租房子,他總是住在酒店裡。他肯定住過成百上千家酒店,而且全都是非常好的酒店。他也來到悉尼,住在岩石區。而且他也不住大房間,你知道有些酒店有超大房間啊,套房啊,但他只住標準間。我問他為什麼?他說:「哦,我已經足夠滿意了。」他說這樣他就不需要顧女傭,酒店有人打掃;而且他購物的次數也少得多,因為酒店房間沒有太多的空間來存放他的東西。諸如此類的理由。你們不覺得這很棒嗎?

It’s life planning. I don’t know what you think, but I think many of us, especially young people, you really need to think about [your] lifestyle, about [adopting] a different kind of lifestyle now. The world has changed. Many of us have been trying to live as we lived before, [but] it doesn’t really apply [any more]. It just gives you more headache anyway. You see? This is dukkha. If you understand dukkha, I think your lifestyle gets better actually. You know what to do. Like, “I may never see Machu Picchu, so I better take a leave [of absence from work]“. Something like that. I think I’ve talked about that in Australia before.

這是一種人生規劃。我不知道你們怎麼想,但我認為很多人,特別是年輕人,真的需要考慮你們的生活方式,考慮其它不同類型的生活方式。世界已經變了。我們中的許多人一直試圖像以前那樣生活,但並不管用,反而只會讓你更頭疼。看到了嗎,這就是「苦」。如果你了解「苦」,你的生活方式會變得更好。你會知道該怎麼做,例如:再不請假,我就可能永遠看不到馬丘比丘了 (譯:秘魯名勝),所以我最好請假。我想我以前在澳大利亞講過這個問題。

Let’s take someone like me. I’m almost sixty. Even if I live to a hundred years, there are only about forty years left. How many pairs of jeans do I need? Forty jeans? Eighty t-shirts? Maybe a hundred toothbrushes? How many pairs of underwear do you reckon? It depends, doesn’t it? But you know what I mean. Planning your life. Understanding dukkha. Because most of the time we don’t know this [i.e. we don’t realize this], so we shop as if we are going to live for a thousand years. So then you get deprived from other aspects of life.

看看像我這樣的人,我快 60 歲了,即使我活到 100 歲,也只剩下大約 40 年,我需要多少東西?四十條牛仔褲?八十件T恤衫?也許一百支牙刷?你猜要多少條內褲?這要看情況? (眾笑) 但你知道我的意思。在規劃你的生活時,請瞭解「苦」。因為大多數時候,我們沒有意識到這一點,我們好像要再活一千年那樣去購物。於是你就被剝奪了生活的其他方面。

So again, understanding dukkha is nothing negative. It’s just simply knowing that there you are [never] going to be a hundred percent satisfied forever and ever. It just doesn’t exist. And in any case, many times you call that aspect “excitement”. Adventure. Understanding that is vipassana. Understanding that intellectually first, and then slowly, slowly getting used to that truth. Okay, so these first two aspects of vipassana [anicca and dukkha] are on the relative level. I would call them relative truth vipassana.

再次強調,理解「苦」絕不是消極負面的。只是單純地了知,你永遠也不會有百分之百的滿足感,不存在的。很多時候你會感覺「興奮」和「刺激」。理解這一點就是我們所說的 Vipassana。首先從理智上理解這一點,然後慢慢地慢慢地習慣於這個事實。Vipassana 的前兩個面向「無常」和「苦」是在相對層面上的,所以我把它們稱為「世俗諦 Vipassana」。

(3) Anatta (nonself)

The third one is anatta. I think we have talked about that enough. Selflessness. Well, I put it in a different way, “It’s there, but it’s not there. It’s not there, but it’s there”. Shunyata. Emptiness. No arising, no cessation, no abiding. No self. [The practice is] getting used to that. However you get used to it doesn’t matter. As long as your action, your motivation, and the method that you apply brings you closer to that [realization of the view of nonself], you are doing vipassana on anatta.

第三個是「無我」。我想我們已經談得夠多了。好吧,我換個說法,可以說「它在那兒,但它不存在」,或者「它不存在,但它就在那兒」。空性,無生,無住,無滅,無我,都是這個意思。請習慣於這些。你如何習慣它並不重要,只要你的行動、你的發心、你的方便方法,使你更接近無我的見地,你就是在做「無我的 Vipassana」。

Again, I’m repeating this, but it’s very important. How you do it really doesn’t matter so much. I would say for most of us, and this is what I’ve been telling my friends and so-called students. After hearing what I have been telling you, yes I think it’s something to do with the definition of practice. Okay, you have heard the view. So how do I practice this? I think the definition of practice always gets hijacked by some sort of ritual. For example, the ritual of sitting every day this much or that much. Chanting this much or that much. Lifestyle. Refraining from certain foods. All this is okay. Fine. But more than that, the definition of practice is how much are you getting used to or closer to the truth? This is what I think you need to apply.

我再次重複這一點,這是非常重要的:你如何做真的無所謂。這也是我一直在告訴我的朋友和所謂的學生的:「在聽聞見地之後,要如何實修呢?」我覺得修行的定義總是被某種儀軌所劫持,比如,這樣打坐,或者那樣打坐,讀誦這些,或者讀誦那些,不吃某些食物,這些全都是生活方式。所有這些都是好的,但更多的是,修行的定義應該是你在多大程度上更習慣更接近真理?這才是你需要應用的東西。

And I’ve been telling many of my friends that I think like for someone like me, maybe the best way is [something like] guilt. Maybe it’s worry or concern. “Am I getting used to this? Am I getting closer to the truth? Am I getting closer to the view?” This concern. You may never sit. Actually, I don’t believe that most of you will sit. Even those who sort of pledge “I will sit every day [for this number of hours]”. Maybe after this [teaching], you may get inspired for about two weeks and then that’s it. You will not do it. I know this. I am a good example myself. I get so charged up and inspired by seeing Bodh Gaya, and then suddenly a few months [go by] and then this kind of inspiration doesn’t last long.

我也一直在告訴我的許多朋友,對於像我這樣的人,也許最好的修行方法是感到內疚和擔心:「我是不是越來越習慣於真理了?我是不是越來越接近實相了?我是不是越來越接近見地了?」這種擔憂。你可能永遠不會去打坐。事實上,我不相信你們中的大多數人會去打坐,即使是那些承諾「我每天都會坐幾個小時」的人。也許在這次教學之後,你可能會受到啟發,大約堅持兩個星期,也就這樣了。我知道這一點,因為我自己就是一個很好的例子。每次看到菩提伽耶,我都很興奮,都有被感染到,突然狂修幾個月,這種啟發不會太長久。

But, you know, I feel guilty [that I’m] not practicing enough. And I’m very happy that I’m feeling this guilt. I feel that this is the blessing of my masters. I think my masters have really given me so much blessing to make me feel guilty that I’m not practicing enough. “I must practice. I must practice. Tomorrow I’m going to practice. Starting from tomorrow, I will do this. New Year’s resolution. I’m going to do this from now on”. I think this is bankable [i.e. you can bank on this] to bring you to the view.

但是,你知道,我很高興我會因為修行不夠多而感到內疚。我覺得這是我的上師們的加持。我認為,我的上師們真的給了我很多很多的加持,才能讓我感到內疚,因為我修得不夠。「我必須修行,我必須修行,明天我就要修行了。」「從明天開始,我將做這些。」「這是新年的決議,我從現在開始要這樣修。」我想這是可以儲存起來的,把你引向見地。

How the Buddha started on his Dharma path in his previous lives

To help you with this, [you can do] prayers. For me, it really works. Prayers. Aspirations. Actually, how did Shakyamuni Buddha [end up becoming the Buddha]? We are now telling a story of course, of how he began his path. We’re not only talking about Shakyamuni as Siddhartha, but we are also talking about his previous lives. Long, long before. Initially. How he began. How he ended up having an awkward feeling. How? There are three reasons, and they are quite interesting.

為了幫助你做到這些,請你祈禱。對我來說,祈禱和發願真的很有效。事實上,釋迦牟尼佛是如何成佛的?我們現在當然是在講一個故事,講他如何開始他的道路。不是在談論釋迦牟尼作為悉達多,而是在談論他的前世。很久很久以前,最初,他是如何開始的?他是如何產生了一種奇怪的感覺?有三個原因,全都相當有趣。

The first reason is that he got so annoyed by pride, his own and others’. That’s number one. The second reason is that he was tired of dukkha. He was tired of this endless unsatisfactoriness. He does this, and he’s not satisfied. He does that, he not satisfied. He was so tired of continuously not being satisfied. He said, “Okay, that’s it. I’ve tried this. I’ve been here, been there. I’ve done this, done that. I’m still not satisfied”. He was tired of that. The third reason is a good one. He realized that these negative emotions, defilements, and attachments are removable. Let’s say he got angry in the morning, and even though he wasn’t doing any spiritual practice or meditation, by the evening he was okay. He wasn’t doing any practice. Nothing. He wasn’t a spiritual person at all. “Oh, that’s funny. So the anger goes? Wow. Emotions don’t stay? Desire doesn’t stay. Wow. Jealousy doesn’t stay? That’s a great thing.” He found that.

第一個原因,他對自己和別人的傲慢產生了厭倦。第二個原因,他對「苦」產生了厭倦,他厭倦了這種無止境的不滿足感。他做了這個,不能滿意。他做了那個,他也不滿意。他對持續的不滿足感到非常厭倦。他說:「好吧,就這樣吧。我已經努力了。我嘗試過這個,嘗試過那個,可我還是不滿意。」他對此感到厭倦了。第三個原因,是一個很好的原因。他意識到這些負面情緒、汙穢和執著是可以被去除的。比方說,他早上生氣了,即使他沒有做任何修行或冥想,但到了晚上他就沒事了。他沒有做任何修行,什麼都沒有,他根本就不是一個搞靈修的人。「哇,很有趣耶,憤怒不會長久,情緒不會長久,慾望不會長久,嫉妒不會長久。。。」這是一個偉大的發現,他發現了這一點。

So with these three he got the motivation [to practice], and he began. And when he began, he did three things. First, he practiced generosity. The second one, and I am always so moved by the second one, is aspiration. Generating that aspiration, generating the motivation. And of course the third one is the most important, which is generating bodhichitta. That’s how he began his Dharma path.

因此,有了這三點,他就有了修行的動力,他就開始了。當他開始時,他做了三件事。首先,他修了佈施。第二,我總是被這第二件事所感動,那就是發願。升起這種願,升起發心。當然,第三件事是最重要的,那就是升起菩提心。這就是他如何開始他的法道。

Should we take a break? I think so. When I talk too much, I lose the thread a little bit. So let’s take a break.

我們應該休息一下嗎?當我說得太多的時候,我就有點忘了前面要說什麼,所以我們休息一下吧。

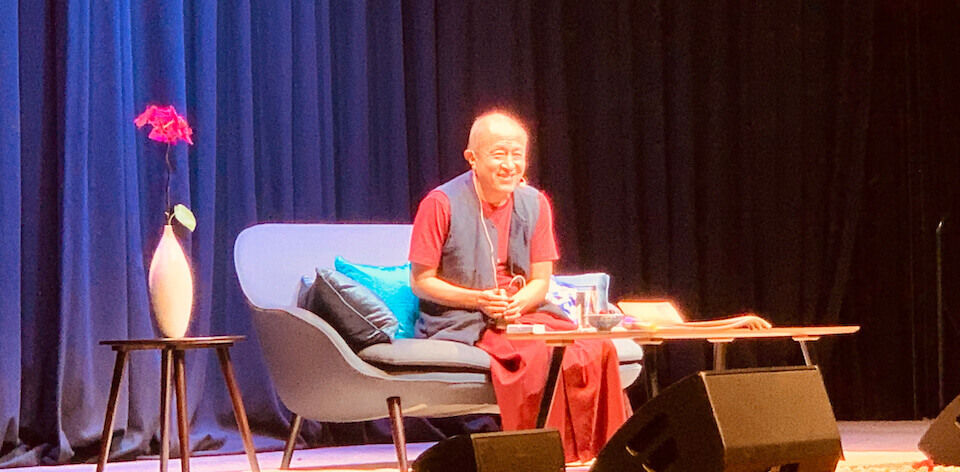

宗薩欽哲仁波切,於 2020年1月25-27日(農曆新年)在澳大利亞悉尼的新南威爾士大學,給予了為期三天的教授,題目為《見修行》。英文部分由 Alex Li Trisoglio(仁波切指定的佛法老師)聽寫,並分段和添加標題,發布在 Madhyamaka.com。中文部分由 孫方 翻譯。並在翻譯過程中,根據視頻做了文字上的修訂,所以中英文部分可能會有可忽略不計的微小差別。照片為課程現場。